Test Your Skill In Distinguishing Obstruction From Ileus

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 3, Case 18

Corinne C. Chan-Nishina, MD

Patrice M.L. Tim-Sing, MD

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

Abdominal radiographs can be difficult to analyze. A

mechanical obstruction is often difficult to differentiate

from an adynamic ileus. The goal of this case

discussion is to help one to have a better understanding

of a mechanical obstruction versus an adynamic

(paralytic) ileus, and be able to make a distinction

between these two conditions. Sixteen abdominal

radiographs will be displayed to test your skill in

distinguishing a bowel obstruction from an ileus.

It is important to first look at those components that

are common to all films, such as the stomach, rectum,

and the hepatic and splenic flexures of the colon.

These areas are relatively fixed. Then, one should look

at the solid abdominal viscera, such as the liver, spleen,

kidneys, psoas muscles and bladder. Finally, an

examination of the lungs (lower portions), diaphragms,

bony structures and pelvis are important.

A mechanical obstruction is an impedance to the

passage of air or intestinal contents secondary to a

mechanical hindrance. Examples of this include

incarcerated inguinal hernia, bowel adhesions,

intussusception, volvulus, intestinal atresias,

intraluminal masses (tumors, bezoars, large stool

masses), and extrinsic bowel compression (Ladd's

bands, annular pancreas, etc.). In a paralytic

(adynamic) ileus, there is a temporary impedance to the

passage of air or contents secondary to uncoordinated

peristalsis or hypoperistalsis.

Adynamic ileus frequently occurs with major

abdominal, retroperitoneal and spinal surgery. It also

occurs frequently with inflammatory processes such as

sepsis, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, appendicitis,

peritonitis, pancreatitis and urinary tract infection. One

may have bowel disturbances and a resultant ileus with

hypokalemia, electrolyte disturbance, dehydration,

vasculitis, renal disease, neurogenic shock, sepsis,

drugs, hypothyroidism and idiopathic intestinal

pseudoobstruction. Although the most common cause

of an ileus is gastroenteritis, an ileus is not necessarily

a benign condition.

There are different criteria that one must look at

when trying to distinguish an ileus from an obstruction

on an abdominal radiograph. These include, the fixed

anatomy, gas distribution, degree of bowel distention,

air fluid levels, and arrangement of the bowel loops. It

should be noted that none of these criteria are

necessarily definitive in always distinguishing an ileus

from an obstruction.

Gas distribution:

A gasless abdomen is usually abnormal. Only rarely

is the abdomen truly gasless. However, radiographs

with an extreme paucity of gas (i.e., almost gasless)

should be treated with the same degree of suspicion as

a gasless abdominal radiograph. Although a gasless

abdomen is highly suggestive of a high obstruction, this

can also be seen with excessive vomiting, and/or

diarrhea. This picture can also occur in the early

stages of appendicitis, as well as in Addisonian crisis

(adrenal crisis). Occasionally, this occurs in patients

with marked cerebral depression such that their

swallowing is impaired.

In a mechanical obstruction, there is preferentially

more air proximal to the obstruction than distal to it.

Thus, in an obstruction, there is either too much gas in

the small bowel (and not much gas in the large bowel),

or too much gas in the large bowel (and not much gas

in the small bowel). In an adynamic ileus, there usually

is no preferential collection of air. There is too much air

or not much air in both the small and large bowel. This

pattern of distribution is not necessarily definitive.

When there is too much air in the small bowel, this may

be a small bowel obstruction which has been present

long enough to have allowed the colon gas to clear.

When there is too much air in the colon, this may be a

large bowel obstruction (e.g.., sigmoid volvulus) with a

competent ileocecal valve. If, however, there is too

much air in both parts of the bowel, you may have a

paralytic ileus, or a large bowel obstruction with an

incompetent ileocecal valve, or a small bowel

obstruction which is early or intermittent.

Another important point is that sometimes in a

mechanical obstruction, there is very little air present

and the intestinal loops are filled with fluid. In these

cases, the loops may appear as opaque sausage-like

structures in the abdomen or the bowel may be

isodense with the rest of the abdomen showing a

paucity of gas. On the upright view, the air may get

trapped in the valvulae conniventes (small bowel plicae

circulares [circular folds]) giving a "string of pearls" gas

pattern appearance.

Bowel dilatation:

Bowel dilatation is another important criteria that

needs to be considered. In a mechanical obstruction

one usually sees dilatation proximal to the site of

obstruction. In a bowel obstruction, the bowel dilatation

appearance in children is different from that generally

seen in adults. In infants and children, an obstruction

characteristically shows dilated bowel with SMOOTH

bowel walls. The degree of dilatation is not necessarily

excessive, but the smoothness of the bowel wall is

most notable. This smoothness is due to the loss of

plicae (circular folds) and haustration of the bowel due

to gaseous distention. In an obstruction where the

bowel is dilated, the bowel resembles "hoses" or

"sausages" where the bowel walls are smooth (the

normal bowel wall irregularity is lost).

Determining the level of the obstruction is often

difficult. It is often difficult to radiographically

distinguish small from large bowel in the infant. In older

children you may see cross striations which represent

the valvulae conniventes when the small bowel is

distended. These resemble the haustra of the large

bowel, however, they are more numerous and more

narrowly spaced. Haustra appear as indentations

which do not cross the lumen like these do, and the

indentations of haustra do not necessarily line up with

the opposite side. In paralytic ileus, the bowel loops all

dilate in proportion to each other. The colon usually

remains larger than the small intestine.

It is worth mentioning here that one can see short

segments of bowel dilatation adjacent to areas of

inflammation ("sentinel" loops). These are areas of

short segment paralytic ileus and when found in the

right upper quadrant, can represent cholecystitis,

pyelonephritis, hepatitis or traumatic disease. In the left

upper quadrant these are seen with pancreatitis,

pyelonephritis, or splenic injury. In the right lower

quadrant, it is seen with appendicitis, Meckel's

diverticulitis, or regional enteritis. These loops are rare

in the left lower quadrant, but can be seen with

salpingitis or cystitis in females.

Air-Fluid levels:

In mechanical obstruction, air-fluid levels can be

seen on the upright view. One can see short air-fluid

levels in both limbs of what look like hairpin loops of

intestine. The heights of the fluid levels are usually

different in any two limbs of one loop (resembles candy

canes). In a paralytic ileus, there may be few to

numerous sluggish air-fluid levels scattered throughout

the abdomen. An obstruction characteristically shows

many dilated air-fluid levels, while an ileus

characteristically shows fewer air-fluid levels that are

not dilated.

Arrangement of Bowel Loops:

One could also look at how orderly the intestinal

loops are arranged. In a mechanical obstruction the

dilated loops are often stacked one under the other in a

"step ladder" appearance (in a more orderly fashion) on

the SUPINE view (not the upright view). With an ileus,

the dilated loops tend to be less orderly, scattered

throughout the abdomen from top to bottom and side to

side. Perhaps another way at describing this

"orderliness", is that an obstruction resembles a bag of

sausages (a more orderly arrangement), while an ileus

resembles a bag of popcorn (a less orderly

arrangement). The sausages of a bowel obstruction

are due to dilated bowel while the popcorn of an ileus is

due to a generalized distribution of bowel gas and

better preservation of the bowel plicae and haustra.

In summary, one should evaluate abdominal films in a

stepwise fashion.

1. Look at the fixed anatomy. Do not forget the lungs.

2. Gas Distribution.

Obstruction: Too much air in the small bowel (and

not much gas in the large bowel) or too much air in the

large bowel (and not much gas in the small bowel).

Poor gas distribution or gasless.

Ileus: Good gas distribution over most of the

abdomen. Too much air in both large and small bowel.

Warning: This could also appear in large bowel

obstruction with an incompetent ileocecal valve, or in an

early or intermittent small bowel obstruction.

3. Bowel Dilatation.

Obstruction: Smooth bowel walls (resembles

sausages or a hose). Preferential dilatation of the

bowel proximal to the obstruction.

Ileus: Dilatation of the bowel in proportion to each

other, so that the colon remains larger than the small

intestine. Look for sentinel loops.

4. Air-fluid Levels.

Obstruction: Many dilated air-fluid levels in both

limbs of a given loop, at different heights (candy canes).

Ileus: Fewer and/or smaller (less dilated) air-fluid

levels scattered throughout the abdomen.

5. Arrangement of loops (supine view only).

Obstruction: Dilated loops arranged in "stepladder"

fashion. Orderly. A bag of sausages.

Ileus: Disorderly loops scattered throughout the

abdomen. A bag of popcorn.

Remember, presentations are variable, and not

always clear cut. Often, it is difficult to distinguish the

two, especially when there is a mixed paralytic and

mechanical obstruction. A high index of suspicion

should remain when the clinical and radiographic

information is unclear. Conditions such as

intussusception, volvulus, and appendicitis are surgical

emergencies that require a timely diagnosis and

intervention. These conditions may not have definitive

findings on plain radiographs. Other diagnostic studies

or surgical intervention may be necessary if these

conditions are still suspected after the completion of

plain film radiographs.

Now test your skill in distinguishing obstruction from

ileus in this series of 16 pediatric abdominal

radiographs. All of these patients are vomiting with

varying degrees of abdominal pain. No histories are

given here except for the patient's age and sex. In

reality, the radiographic findings should be interpreted in

conjunction with the patient's clinical findings. Two

views are shown in each case. The view on the left is a

supine view. The view on the right is an upright view

unless otherwise specified.

Case A: 18-month old male.

View Case A.

Interpretation of Case A

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: No excessively dilated bowel. The

bowel walls are not smooth. Haustra and plicae are

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Large loops are not present.

Impression: Within normal limits.

Case B: 7-day old female.

View Case B.

Interpretation of Case A

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: No excessively dilated bowel. The

bowel walls are not smooth. Haustra and plicae are

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Large loops are not present.

Impression: Within normal limits.

Case B: 7-day old female.

View Case B.

Interpretation of Case B

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: There is mild dilation of the bowel,

mostly in the colon. The dilated segment of bowel in

the left upper quadrant shows relatively smooth bowel

walls. However, most of the bowel does not show this.

In other words, the haustra and plicae of most of the

bowel are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are not arranged

in an orderly pattern.

Impression: Ileus.

Case C: 17-day old male.

View Case C.

Interpretation of Case B

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: There is mild dilation of the bowel,

mostly in the colon. The dilated segment of bowel in

the left upper quadrant shows relatively smooth bowel

walls. However, most of the bowel does not show this.

In other words, the haustra and plicae of most of the

bowel are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are not arranged

in an orderly pattern.

Impression: Ileus.

Case C: 17-day old male.

View Case C.

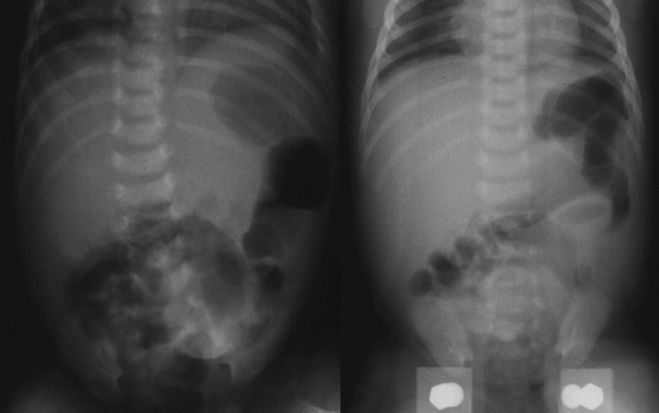

Interpretation of Case C

Gas Distribution: There is gas over most of the

abdomen. There are loops of bowel mostly in the

central abdomen. The dilated loops are mostly small

bowel.

Bowel Dilatation: The bowel walls are smooth

indicating that the bowel is dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are multiple short air fluid

levels on the upright film (hair pin loops).

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly, although not truly in

a stepladder fashion. The arrangement here resembles

a bag of sausages more so that a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Small bowel obstruction. In this age,

the mostly likely cause is an incarcerated inguinal

hernia. This is confirmed clinically.

Case D: 1-month old female.

View Case D.

Interpretation of Case C

Gas Distribution: There is gas over most of the

abdomen. There are loops of bowel mostly in the

central abdomen. The dilated loops are mostly small

bowel.

Bowel Dilatation: The bowel walls are smooth

indicating that the bowel is dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are multiple short air fluid

levels on the upright film (hair pin loops).

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly, although not truly in

a stepladder fashion. The arrangement here resembles

a bag of sausages more so that a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Small bowel obstruction. In this age,

the mostly likely cause is an incarcerated inguinal

hernia. This is confirmed clinically.

Case D: 1-month old female.

View Case D.

Interpretation of Case D

Gas Distribution: There is a lot of gas in the small

and large bowel distributed throughout the abdomen.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilation here

is proportional throughout. In other words, the large

bowel is slightly dilated, as is the small bowel.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement of

dilated bowel. This resembles a bag of popcorn rather

than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. The differential is extensive,

including gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, etc.

However, an ileus is still compatible with several

surgical conditions such as appendicitis.

Case E: 3-1/2 year old male.

View Case E.

Interpretation of Case D

Gas Distribution: There is a lot of gas in the small

and large bowel distributed throughout the abdomen.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilation here

is proportional throughout. In other words, the large

bowel is slightly dilated, as is the small bowel.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement of

dilated bowel. This resembles a bag of popcorn rather

than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. The differential is extensive,

including gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, etc.

However, an ileus is still compatible with several

surgical conditions such as appendicitis.

Case E: 3-1/2 year old male.

View Case E.

Interpretation of Case E

Gas Distribution: Increased gaseous distribution in

both small and large bowel, with more colonic

involvement. Gas is also present in the rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: Note the smooth bowel walls

resulting in the "sausage-like" appearance of some of

the loops. There are several areas of extreme dilation.

The stomach is also very dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple loops of bowel with air

fluid levels. The typical "candy cane" appearance is not

very dramatic.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are stacked in a

somewhat orderly fashion. However, this is not definite.

The "arrangement" should be best determined on the

supine flat view and not the upright view. Although this

arrangement resembles a bag of sausages more so

than a bag of popcorn, this is not as clear-cut as in

other cases.

Impression: The gas distribution throughout the

bowel suggests that this is not an obstruction.

However, the reason for the extreme bowel dilatation is

uncertain. This is still suspicious for an obstruction.

Note the frothy density over the left flank area (supine

view). This probably represents fecal matter. Though a

fecal obstruction is possible, a BE or an UGI series

would be helpful to evaluate other causes of obstruction

such as malrotation or Hirshsprung's disease. A

contrast enema and an UGI series were performed on

this patient. Both were normal. His symptoms and

bowel dilation gradually resolved after several enemas

and bowel movements.

Case F: 7-month old male.

View Case F.

Interpretation of Case E

Gas Distribution: Increased gaseous distribution in

both small and large bowel, with more colonic

involvement. Gas is also present in the rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: Note the smooth bowel walls

resulting in the "sausage-like" appearance of some of

the loops. There are several areas of extreme dilation.

The stomach is also very dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple loops of bowel with air

fluid levels. The typical "candy cane" appearance is not

very dramatic.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are stacked in a

somewhat orderly fashion. However, this is not definite.

The "arrangement" should be best determined on the

supine flat view and not the upright view. Although this

arrangement resembles a bag of sausages more so

than a bag of popcorn, this is not as clear-cut as in

other cases.

Impression: The gas distribution throughout the

bowel suggests that this is not an obstruction.

However, the reason for the extreme bowel dilatation is

uncertain. This is still suspicious for an obstruction.

Note the frothy density over the left flank area (supine

view). This probably represents fecal matter. Though a

fecal obstruction is possible, a BE or an UGI series

would be helpful to evaluate other causes of obstruction

such as malrotation or Hirshsprung's disease. A

contrast enema and an UGI series were performed on

this patient. Both were normal. His symptoms and

bowel dilation gradually resolved after several enemas

and bowel movements.

Case F: 7-month old male.

View Case F.

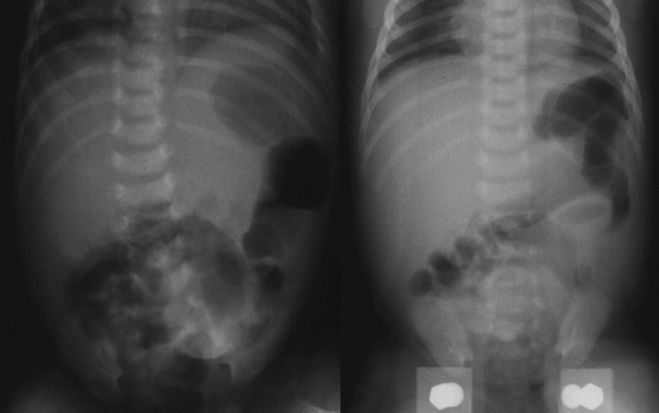

Interpretation of Case F

Gas Distribution: Relatively gasless in both large

and small bowel. This is a poor gas distribution.

Bowel Dilatation: In some of the few bowel loops

that are seen, the bowel walls appear smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are no obvious air-fluid

levels. However, in the upright view, the central

abdomen shows the presence of two bowel loops

resembling arches that are air-fluid levels which do not

have the typical candy cane appearance. The candy

cane appearance of air-fluid levels is usually not seen in

infants.

Arrangement of Loops: It is difficult to comment on

the arrangement given the minimal gas pattern.

Impression: Probable obstruction based mainly on

the paucity of gas and its distribution. Since these

radiographs are highly suspicious, the next

recommended exam should be an ultrasound and/or a

BE to evaluate the possibility of intussusception or

appendicitis. An intussusception is often the cause of a

bowel obstruction associated with a paucity of gas on

plain radiographs A BE performed in this patient

demonstrated an intussusception.

Case G: Newborn male.

View Case G.

Interpretation of Case F

Gas Distribution: Relatively gasless in both large

and small bowel. This is a poor gas distribution.

Bowel Dilatation: In some of the few bowel loops

that are seen, the bowel walls appear smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are no obvious air-fluid

levels. However, in the upright view, the central

abdomen shows the presence of two bowel loops

resembling arches that are air-fluid levels which do not

have the typical candy cane appearance. The candy

cane appearance of air-fluid levels is usually not seen in

infants.

Arrangement of Loops: It is difficult to comment on

the arrangement given the minimal gas pattern.

Impression: Probable obstruction based mainly on

the paucity of gas and its distribution. Since these

radiographs are highly suspicious, the next

recommended exam should be an ultrasound and/or a

BE to evaluate the possibility of intussusception or

appendicitis. An intussusception is often the cause of a

bowel obstruction associated with a paucity of gas on

plain radiographs A BE performed in this patient

demonstrated an intussusception.

Case G: Newborn male.

View Case G.

Interpretation of Case G

In this case, only a supine view is shown on the left.

The image on the right is a contrast enema study.

Gas Distribution: There is poor gas distribution with

only 3 dilated loops of bowel, triple bubbles, probably

representing high (i.e., proximal) small bowel loops.

There is some gas in the left lower quadrant. This

cannot be the colon since there is no gas in any other

intervening bowel segments evident.

Bowel Dilatation: As noted above, dilation is present

in the loops seen. There is no colon gas evident.

Air-Fluid Levels: An upright or lateral decubitus view

is not shown here.

Arrangement of Loops: Too few to comment.

Impression: This is a proximal small bowel

obstruction. The contrast enema on the right shows a

microcolon indicating the absence of bowel contents

passing to the colon during gestation. In a proximal

small bowel obstruction, a microcolon is usually not

present. The presence of a microcolon suggests that

the distal small bowel is also atretic. This patient was

ultimately diagnosed with a long segment small bowel

atresia. Note that the contrast enema study also shows

the cecum in the wrong position. It should be in the

right lower quadrant, but it appears to be more medial

than its expected positions. Malpositioning of the

cecum is highly indicative of a malrotation.

Case H: 3-day old female.

View Case H.

Interpretation of Case G

In this case, only a supine view is shown on the left.

The image on the right is a contrast enema study.

Gas Distribution: There is poor gas distribution with

only 3 dilated loops of bowel, triple bubbles, probably

representing high (i.e., proximal) small bowel loops.

There is some gas in the left lower quadrant. This

cannot be the colon since there is no gas in any other

intervening bowel segments evident.

Bowel Dilatation: As noted above, dilation is present

in the loops seen. There is no colon gas evident.

Air-Fluid Levels: An upright or lateral decubitus view

is not shown here.

Arrangement of Loops: Too few to comment.

Impression: This is a proximal small bowel

obstruction. The contrast enema on the right shows a

microcolon indicating the absence of bowel contents

passing to the colon during gestation. In a proximal

small bowel obstruction, a microcolon is usually not

present. The presence of a microcolon suggests that

the distal small bowel is also atretic. This patient was

ultimately diagnosed with a long segment small bowel

atresia. Note that the contrast enema study also shows

the cecum in the wrong position. It should be in the

right lower quadrant, but it appears to be more medial

than its expected positions. Malpositioning of the

cecum is highly indicative of a malrotation.

Case H: 3-day old female.

View Case H.

Interpretation of Case H

Gas Distribution: Generalized presence of gas

throughout all quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilatation is

proportional. The right lower quadrant may

demonstrate some smooth bowel walls, but this is

probably just the descending colon. Some of the

haustra in these segments are still preserved. For the

remainder of the bowel, the haustra and plicae are well

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Ileus.

Case I: 2-1/2 year old female.

View Case I.

Interpretation of Case H

Gas Distribution: Generalized presence of gas

throughout all quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilatation is

proportional. The right lower quadrant may

demonstrate some smooth bowel walls, but this is

probably just the descending colon. Some of the

haustra in these segments are still preserved. For the

remainder of the bowel, the haustra and plicae are well

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Ileus.

Case I: 2-1/2 year old female.

View Case I.

Interpretation of Case I

Gas Distribution: Well distributed throughout all

quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated regions

seen on the supine view in both lower quadrants.

However, the bowel walls do not appear smooth. The

typical sausage or hose appearance of dilated small

bowel is not present. The haustra and plicae are still

fairly well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: The upright view shows many

small air fluid levels. The typical hairpin or candy cane

appearance is not present indicating that these air

fluid levels are small and not present in large loops.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly loops resembling

a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of sausages

(supine view).

Impression: Moderate ileus versus partial

obstruction. An ileus is more likely.

Case J: 3-year old female.

View Case J.

Interpretation of Case I

Gas Distribution: Well distributed throughout all

quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated regions

seen on the supine view in both lower quadrants.

However, the bowel walls do not appear smooth. The

typical sausage or hose appearance of dilated small

bowel is not present. The haustra and plicae are still

fairly well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: The upright view shows many

small air fluid levels. The typical hairpin or candy cane

appearance is not present indicating that these air

fluid levels are small and not present in large loops.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly loops resembling

a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of sausages

(supine view).

Impression: Moderate ileus versus partial

obstruction. An ileus is more likely.

Case J: 3-year old female.

View Case J.

Interpretation of Case J

Gas Distribution: There is gas distributed

throughout the abdomen. Most of the gas present is in

the colon.

Bowel Dilatation: There is moderate dilation of the

colonic regions. There is a dilated loop of small bowel

on the left (supine view) which overlaps the colon. The

haustra and plicae are preserved. No sausages or

hoses are seen (i.e., no smooth bowel walls are

present).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of

sausages.

Impression: Ileus.

Case K: 9-day old male.

View Case K.

Interpretation of Case J

Gas Distribution: There is gas distributed

throughout the abdomen. Most of the gas present is in

the colon.

Bowel Dilatation: There is moderate dilation of the

colonic regions. There is a dilated loop of small bowel

on the left (supine view) which overlaps the colon. The

haustra and plicae are preserved. No sausages or

hoses are seen (i.e., no smooth bowel walls are

present).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of

sausages.

Impression: Ileus.

Case K: 9-day old male.

View Case K.

Interpretation of Case K

Gas Distribution: Poor distribution. Although gas is

present throughout most of the abdomen, its distribution

appears to be limited to just a few bowel segments.

Bowel Dilatation: Marked bowel distention though

difficult to determine small versus large bowel. The

bowel walls are smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple air-fluid levels mostly on

the left. Hair pins and candy canes are not present.

Arrangement of Loops: Not very helpful in this case.

The arrangement is best evaluated on the supine view

which is not obviously orderly or disorderly. In other

words, it is not easy to say whether this arrangement

resembles a bag of sausages or a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction based mainly on the gas

distribution and the degree of bowel dilatation. This is

not a normal abdominal series for a 9-day old. A

contrast enema demonstrated a transition zone

consistent with Hirschsprung's disease.

Case L: 12-month old female.

View Case L.

Interpretation of Case K

Gas Distribution: Poor distribution. Although gas is

present throughout most of the abdomen, its distribution

appears to be limited to just a few bowel segments.

Bowel Dilatation: Marked bowel distention though

difficult to determine small versus large bowel. The

bowel walls are smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple air-fluid levels mostly on

the left. Hair pins and candy canes are not present.

Arrangement of Loops: Not very helpful in this case.

The arrangement is best evaluated on the supine view

which is not obviously orderly or disorderly. In other

words, it is not easy to say whether this arrangement

resembles a bag of sausages or a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction based mainly on the gas

distribution and the degree of bowel dilatation. This is

not a normal abdominal series for a 9-day old. A

contrast enema demonstrated a transition zone

consistent with Hirschsprung's disease.

Case L: 12-month old female.

View Case L.

Interpretation of Case L

Gas Distribution: Small areas of gas are present

throughout the entire abdomen. Many of the areas are

foamy suggesting the presence of excessive amounts

of stool.

Bowel Dilatation: Most of the bowel is not dilated.

There is a modest paucity of gas. There are two dilated

loops in the RLQ on the supine view (RLQ sentinel

loops).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Despite the

paucity of gas, the supine view resembles a bag of

popcorn more so than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. RLQ sentinel loops raise the

possibility of appendicitis.

Case M: 7-month old female.

View Case M.

Interpretation of Case L

Gas Distribution: Small areas of gas are present

throughout the entire abdomen. Many of the areas are

foamy suggesting the presence of excessive amounts

of stool.

Bowel Dilatation: Most of the bowel is not dilated.

There is a modest paucity of gas. There are two dilated

loops in the RLQ on the supine view (RLQ sentinel

loops).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Despite the

paucity of gas, the supine view resembles a bag of

popcorn more so than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. RLQ sentinel loops raise the

possibility of appendicitis.

Case M: 7-month old female.

View Case M.

Interpretation of Case M

Gas Distribution: There is a definite paucity of gas

which is poorly distributed.

Bowel Dilatation: Nothing obvious.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Not a useful sign here

because of the paucity of gas.

Other comments: There is a "target sign" in the

right upper quadrant. The target sign is discussed in

detail in Case 2 of Volume 1. The target is faintly

visible as a doughnut shape (with the doughnut center

still present) in the right upper quadrant below the liver

(supine view). This is subtle. You may have to turn

down the room lights and adjust the contrast and

brightness on your monitor. This sign indicates the

presence of an intussusception. This radiograph also

demonstrates the "absent liver edge" sign (liver edge

not well defined in any view), which is also a sign of

intussusception (though less specific than the target

sign). If you have difficulty identifying the target and

liver edge findings in this radiograph, review Case 2 of

Volume 1 for other examples that are easier to identify.

Impression: Suggestive of an obstruction based

mainly on the paucity of gas. The target sign indicates

the presence of an intussusception. A barium enema

confirmed an intussusception.

Case N: 22-month old.

View Case N.

Interpretation of Case M

Gas Distribution: There is a definite paucity of gas

which is poorly distributed.

Bowel Dilatation: Nothing obvious.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Not a useful sign here

because of the paucity of gas.

Other comments: There is a "target sign" in the

right upper quadrant. The target sign is discussed in

detail in Case 2 of Volume 1. The target is faintly

visible as a doughnut shape (with the doughnut center

still present) in the right upper quadrant below the liver

(supine view). This is subtle. You may have to turn

down the room lights and adjust the contrast and

brightness on your monitor. This sign indicates the

presence of an intussusception. This radiograph also

demonstrates the "absent liver edge" sign (liver edge

not well defined in any view), which is also a sign of

intussusception (though less specific than the target

sign). If you have difficulty identifying the target and

liver edge findings in this radiograph, review Case 2 of

Volume 1 for other examples that are easier to identify.

Impression: Suggestive of an obstruction based

mainly on the paucity of gas. The target sign indicates

the presence of an intussusception. A barium enema

confirmed an intussusception.

Case N: 22-month old.

View Case N.

Interpretation of Case N

Gas Distribution: Good distribution except for one

portion in the LUQ. Although the upright view appears

to be somewhat gasless with most of the gas seen

localized to the upper abdomen only, the supine view

shows a better distribution of gas.

Bowel Dilatation: There are no dilated regions. The

haustra and plicae are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly.

Other Comments: The supine view demonstrates

"thumb printing" suggesting bowel wall edema such as

that seen in colitis. This is best seen in the LUQ

region (or left middle region) where the colon shows

thumb-shaped indentations into its lumen.

Impression: Ileus, colitis.

Case O: 11-month old male.

View Case O.

Interpretation of Case N

Gas Distribution: Good distribution except for one

portion in the LUQ. Although the upright view appears

to be somewhat gasless with most of the gas seen

localized to the upper abdomen only, the supine view

shows a better distribution of gas.

Bowel Dilatation: There are no dilated regions. The

haustra and plicae are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly.

Other Comments: The supine view demonstrates

"thumb printing" suggesting bowel wall edema such as

that seen in colitis. This is best seen in the LUQ

region (or left middle region) where the colon shows

thumb-shaped indentations into its lumen.

Impression: Ileus, colitis.

Case O: 11-month old male.

View Case O.

Interpretation of Case O

Gas Distribution: Poorly distributed. Gas is

concentrated in the left upper quadrants in both the

supine and upright views.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated bowel

segments seen on the supine view. The bowel walls

are smooth and resemble sausages.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly. Note the two

dilated bowel segments on the supine view are stacked

on top of each other resembling a step ladder. Also,

this view clearly resembles a bag of sausages (only two

big ones), rather than a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction. A barium enema in this

case demonstrated intussusception.

Case P: 6-1/2 year old male.

View Case P.

Interpretation of Case O

Gas Distribution: Poorly distributed. Gas is

concentrated in the left upper quadrants in both the

supine and upright views.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated bowel

segments seen on the supine view. The bowel walls

are smooth and resemble sausages.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly. Note the two

dilated bowel segments on the supine view are stacked

on top of each other resembling a step ladder. Also,

this view clearly resembles a bag of sausages (only two

big ones), rather than a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction. A barium enema in this

case demonstrated intussusception.

Case P: 6-1/2 year old male.

View Case P.

Interpretation of Case P

Gas Distribution: Well distributed except for a

paucity of gas in the left lower quadrant.

Bowel Dilatation: The haustra and plicae are well

preserved. No smooth bowel walls are visible. The

caliber of the bowel is proportional to the normal bowel

size.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Does not

resemble a bag of sausages. Nor does it truly

resemble a bag of popcorn. However, there is no order

to the arrangement.

Impression: Ileus. There is a possible appendicolith

in the right lower quadrant (spherical density). This is

highly suggestive of acute appendicitis. This again

stresses the point, that an ileus is not necessarily

benign.

References

1. Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Radiology of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

second edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1986,

pp. 153-164.

2. Swischuk LE. The Alimentary Tract. In:

Radiology of the Newborn and Young Infant, second

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1980, pp.

487-490.

3. Kirks DR. The Gastrointestinal Tract. In:

Practical Pediatric and Diagnostic Radiology of Infants

and Children. Boston, Little, Brown and Company,

1984, pp. 551-553.

4. Parker BR. The Abdomen and Gastrointestinal

Tract. In: Silverman FN, Kuhn JP. Caffey's Pediatric

X-Ray Diagnosis, Ninth edition. St. Louis, Mosby,

1993, pp. 1059-1089.

5. Squire LF, Novelline RA. The Abdominal Plain

Film: Distended Stomach, Small Bowel, Colon, Free

Fluid and Free Air. In: Fundamentals of Radiology, 4th

edition. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press,

1988, pp. 194-205.

Interpretation of Case P

Gas Distribution: Well distributed except for a

paucity of gas in the left lower quadrant.

Bowel Dilatation: The haustra and plicae are well

preserved. No smooth bowel walls are visible. The

caliber of the bowel is proportional to the normal bowel

size.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Does not

resemble a bag of sausages. Nor does it truly

resemble a bag of popcorn. However, there is no order

to the arrangement.

Impression: Ileus. There is a possible appendicolith

in the right lower quadrant (spherical density). This is

highly suggestive of acute appendicitis. This again

stresses the point, that an ileus is not necessarily

benign.

References

1. Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Radiology of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

second edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1986,

pp. 153-164.

2. Swischuk LE. The Alimentary Tract. In:

Radiology of the Newborn and Young Infant, second

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1980, pp.

487-490.

3. Kirks DR. The Gastrointestinal Tract. In:

Practical Pediatric and Diagnostic Radiology of Infants

and Children. Boston, Little, Brown and Company,

1984, pp. 551-553.

4. Parker BR. The Abdomen and Gastrointestinal

Tract. In: Silverman FN, Kuhn JP. Caffey's Pediatric

X-Ray Diagnosis, Ninth edition. St. Louis, Mosby,

1993, pp. 1059-1089.

5. Squire LF, Novelline RA. The Abdominal Plain

Film: Distended Stomach, Small Bowel, Colon, Free

Fluid and Free Air. In: Fundamentals of Radiology, 4th

edition. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press,

1988, pp. 194-205.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

Interpretation of Case A

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: No excessively dilated bowel. The

bowel walls are not smooth. Haustra and plicae are

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Large loops are not present.

Impression: Within normal limits.

Case B: 7-day old female.

View Case B.

Interpretation of Case A

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: No excessively dilated bowel. The

bowel walls are not smooth. Haustra and plicae are

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Large loops are not present.

Impression: Within normal limits.

Case B: 7-day old female.

View Case B.

Interpretation of Case B

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: There is mild dilation of the bowel,

mostly in the colon. The dilated segment of bowel in

the left upper quadrant shows relatively smooth bowel

walls. However, most of the bowel does not show this.

In other words, the haustra and plicae of most of the

bowel are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are not arranged

in an orderly pattern.

Impression: Ileus.

Case C: 17-day old male.

View Case C.

Interpretation of Case B

Gas Distribution: There are pockets of gas

scattered in several areas of the abdomen. There is

gas in the small bowel, colon, and rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: There is mild dilation of the bowel,

mostly in the colon. The dilated segment of bowel in

the left upper quadrant shows relatively smooth bowel

walls. However, most of the bowel does not show this.

In other words, the haustra and plicae of most of the

bowel are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are not arranged

in an orderly pattern.

Impression: Ileus.

Case C: 17-day old male.

View Case C.

Interpretation of Case C

Gas Distribution: There is gas over most of the

abdomen. There are loops of bowel mostly in the

central abdomen. The dilated loops are mostly small

bowel.

Bowel Dilatation: The bowel walls are smooth

indicating that the bowel is dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are multiple short air fluid

levels on the upright film (hair pin loops).

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly, although not truly in

a stepladder fashion. The arrangement here resembles

a bag of sausages more so that a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Small bowel obstruction. In this age,

the mostly likely cause is an incarcerated inguinal

hernia. This is confirmed clinically.

Case D: 1-month old female.

View Case D.

Interpretation of Case C

Gas Distribution: There is gas over most of the

abdomen. There are loops of bowel mostly in the

central abdomen. The dilated loops are mostly small

bowel.

Bowel Dilatation: The bowel walls are smooth

indicating that the bowel is dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are multiple short air fluid

levels on the upright film (hair pin loops).

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly, although not truly in

a stepladder fashion. The arrangement here resembles

a bag of sausages more so that a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Small bowel obstruction. In this age,

the mostly likely cause is an incarcerated inguinal

hernia. This is confirmed clinically.

Case D: 1-month old female.

View Case D.

Interpretation of Case D

Gas Distribution: There is a lot of gas in the small

and large bowel distributed throughout the abdomen.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilation here

is proportional throughout. In other words, the large

bowel is slightly dilated, as is the small bowel.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement of

dilated bowel. This resembles a bag of popcorn rather

than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. The differential is extensive,

including gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, etc.

However, an ileus is still compatible with several

surgical conditions such as appendicitis.

Case E: 3-1/2 year old male.

View Case E.

Interpretation of Case D

Gas Distribution: There is a lot of gas in the small

and large bowel distributed throughout the abdomen.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilation here

is proportional throughout. In other words, the large

bowel is slightly dilated, as is the small bowel.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement of

dilated bowel. This resembles a bag of popcorn rather

than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. The differential is extensive,

including gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, etc.

However, an ileus is still compatible with several

surgical conditions such as appendicitis.

Case E: 3-1/2 year old male.

View Case E.

Interpretation of Case E

Gas Distribution: Increased gaseous distribution in

both small and large bowel, with more colonic

involvement. Gas is also present in the rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: Note the smooth bowel walls

resulting in the "sausage-like" appearance of some of

the loops. There are several areas of extreme dilation.

The stomach is also very dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple loops of bowel with air

fluid levels. The typical "candy cane" appearance is not

very dramatic.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are stacked in a

somewhat orderly fashion. However, this is not definite.

The "arrangement" should be best determined on the

supine flat view and not the upright view. Although this

arrangement resembles a bag of sausages more so

than a bag of popcorn, this is not as clear-cut as in

other cases.

Impression: The gas distribution throughout the

bowel suggests that this is not an obstruction.

However, the reason for the extreme bowel dilatation is

uncertain. This is still suspicious for an obstruction.

Note the frothy density over the left flank area (supine

view). This probably represents fecal matter. Though a

fecal obstruction is possible, a BE or an UGI series

would be helpful to evaluate other causes of obstruction

such as malrotation or Hirshsprung's disease. A

contrast enema and an UGI series were performed on

this patient. Both were normal. His symptoms and

bowel dilation gradually resolved after several enemas

and bowel movements.

Case F: 7-month old male.

View Case F.

Interpretation of Case E

Gas Distribution: Increased gaseous distribution in

both small and large bowel, with more colonic

involvement. Gas is also present in the rectum.

Bowel Dilatation: Note the smooth bowel walls

resulting in the "sausage-like" appearance of some of

the loops. There are several areas of extreme dilation.

The stomach is also very dilated.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple loops of bowel with air

fluid levels. The typical "candy cane" appearance is not

very dramatic.

Arrangement of Loops: The loops are stacked in a

somewhat orderly fashion. However, this is not definite.

The "arrangement" should be best determined on the

supine flat view and not the upright view. Although this

arrangement resembles a bag of sausages more so

than a bag of popcorn, this is not as clear-cut as in

other cases.

Impression: The gas distribution throughout the

bowel suggests that this is not an obstruction.

However, the reason for the extreme bowel dilatation is

uncertain. This is still suspicious for an obstruction.

Note the frothy density over the left flank area (supine

view). This probably represents fecal matter. Though a

fecal obstruction is possible, a BE or an UGI series

would be helpful to evaluate other causes of obstruction

such as malrotation or Hirshsprung's disease. A

contrast enema and an UGI series were performed on

this patient. Both were normal. His symptoms and

bowel dilation gradually resolved after several enemas

and bowel movements.

Case F: 7-month old male.

View Case F.

Interpretation of Case F

Gas Distribution: Relatively gasless in both large

and small bowel. This is a poor gas distribution.

Bowel Dilatation: In some of the few bowel loops

that are seen, the bowel walls appear smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are no obvious air-fluid

levels. However, in the upright view, the central

abdomen shows the presence of two bowel loops

resembling arches that are air-fluid levels which do not

have the typical candy cane appearance. The candy

cane appearance of air-fluid levels is usually not seen in

infants.

Arrangement of Loops: It is difficult to comment on

the arrangement given the minimal gas pattern.

Impression: Probable obstruction based mainly on

the paucity of gas and its distribution. Since these

radiographs are highly suspicious, the next

recommended exam should be an ultrasound and/or a

BE to evaluate the possibility of intussusception or

appendicitis. An intussusception is often the cause of a

bowel obstruction associated with a paucity of gas on

plain radiographs A BE performed in this patient

demonstrated an intussusception.

Case G: Newborn male.

View Case G.

Interpretation of Case F

Gas Distribution: Relatively gasless in both large

and small bowel. This is a poor gas distribution.

Bowel Dilatation: In some of the few bowel loops

that are seen, the bowel walls appear smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: There are no obvious air-fluid

levels. However, in the upright view, the central

abdomen shows the presence of two bowel loops

resembling arches that are air-fluid levels which do not

have the typical candy cane appearance. The candy

cane appearance of air-fluid levels is usually not seen in

infants.

Arrangement of Loops: It is difficult to comment on

the arrangement given the minimal gas pattern.

Impression: Probable obstruction based mainly on

the paucity of gas and its distribution. Since these

radiographs are highly suspicious, the next

recommended exam should be an ultrasound and/or a

BE to evaluate the possibility of intussusception or

appendicitis. An intussusception is often the cause of a

bowel obstruction associated with a paucity of gas on

plain radiographs A BE performed in this patient

demonstrated an intussusception.

Case G: Newborn male.

View Case G.

Interpretation of Case G

In this case, only a supine view is shown on the left.

The image on the right is a contrast enema study.

Gas Distribution: There is poor gas distribution with

only 3 dilated loops of bowel, triple bubbles, probably

representing high (i.e., proximal) small bowel loops.

There is some gas in the left lower quadrant. This

cannot be the colon since there is no gas in any other

intervening bowel segments evident.

Bowel Dilatation: As noted above, dilation is present

in the loops seen. There is no colon gas evident.

Air-Fluid Levels: An upright or lateral decubitus view

is not shown here.

Arrangement of Loops: Too few to comment.

Impression: This is a proximal small bowel

obstruction. The contrast enema on the right shows a

microcolon indicating the absence of bowel contents

passing to the colon during gestation. In a proximal

small bowel obstruction, a microcolon is usually not

present. The presence of a microcolon suggests that

the distal small bowel is also atretic. This patient was

ultimately diagnosed with a long segment small bowel

atresia. Note that the contrast enema study also shows

the cecum in the wrong position. It should be in the

right lower quadrant, but it appears to be more medial

than its expected positions. Malpositioning of the

cecum is highly indicative of a malrotation.

Case H: 3-day old female.

View Case H.

Interpretation of Case G

In this case, only a supine view is shown on the left.

The image on the right is a contrast enema study.

Gas Distribution: There is poor gas distribution with

only 3 dilated loops of bowel, triple bubbles, probably

representing high (i.e., proximal) small bowel loops.

There is some gas in the left lower quadrant. This

cannot be the colon since there is no gas in any other

intervening bowel segments evident.

Bowel Dilatation: As noted above, dilation is present

in the loops seen. There is no colon gas evident.

Air-Fluid Levels: An upright or lateral decubitus view

is not shown here.

Arrangement of Loops: Too few to comment.

Impression: This is a proximal small bowel

obstruction. The contrast enema on the right shows a

microcolon indicating the absence of bowel contents

passing to the colon during gestation. In a proximal

small bowel obstruction, a microcolon is usually not

present. The presence of a microcolon suggests that

the distal small bowel is also atretic. This patient was

ultimately diagnosed with a long segment small bowel

atresia. Note that the contrast enema study also shows

the cecum in the wrong position. It should be in the

right lower quadrant, but it appears to be more medial

than its expected positions. Malpositioning of the

cecum is highly indicative of a malrotation.

Case H: 3-day old female.

View Case H.

Interpretation of Case H

Gas Distribution: Generalized presence of gas

throughout all quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilatation is

proportional. The right lower quadrant may

demonstrate some smooth bowel walls, but this is

probably just the descending colon. Some of the

haustra in these segments are still preserved. For the

remainder of the bowel, the haustra and plicae are well

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Ileus.

Case I: 2-1/2 year old female.

View Case I.

Interpretation of Case H

Gas Distribution: Generalized presence of gas

throughout all quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: The degree of bowel dilatation is

proportional. The right lower quadrant may

demonstrate some smooth bowel walls, but this is

probably just the descending colon. Some of the

haustra in these segments are still preserved. For the

remainder of the bowel, the haustra and plicae are well

preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Ileus.

Case I: 2-1/2 year old female.

View Case I.

Interpretation of Case I

Gas Distribution: Well distributed throughout all

quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated regions

seen on the supine view in both lower quadrants.

However, the bowel walls do not appear smooth. The

typical sausage or hose appearance of dilated small

bowel is not present. The haustra and plicae are still

fairly well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: The upright view shows many

small air fluid levels. The typical hairpin or candy cane

appearance is not present indicating that these air

fluid levels are small and not present in large loops.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly loops resembling

a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of sausages

(supine view).

Impression: Moderate ileus versus partial

obstruction. An ileus is more likely.

Case J: 3-year old female.

View Case J.

Interpretation of Case I

Gas Distribution: Well distributed throughout all

quadrants.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated regions

seen on the supine view in both lower quadrants.

However, the bowel walls do not appear smooth. The

typical sausage or hose appearance of dilated small

bowel is not present. The haustra and plicae are still

fairly well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: The upright view shows many

small air fluid levels. The typical hairpin or candy cane

appearance is not present indicating that these air

fluid levels are small and not present in large loops.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly loops resembling

a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of sausages

(supine view).

Impression: Moderate ileus versus partial

obstruction. An ileus is more likely.

Case J: 3-year old female.

View Case J.

Interpretation of Case J

Gas Distribution: There is gas distributed

throughout the abdomen. Most of the gas present is in

the colon.

Bowel Dilatation: There is moderate dilation of the

colonic regions. There is a dilated loop of small bowel

on the left (supine view) which overlaps the colon. The

haustra and plicae are preserved. No sausages or

hoses are seen (i.e., no smooth bowel walls are

present).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of

sausages.

Impression: Ileus.

Case K: 9-day old male.

View Case K.

Interpretation of Case J

Gas Distribution: There is gas distributed

throughout the abdomen. Most of the gas present is in

the colon.

Bowel Dilatation: There is moderate dilation of the

colonic regions. There is a dilated loop of small bowel

on the left (supine view) which overlaps the colon. The

haustra and plicae are preserved. No sausages or

hoses are seen (i.e., no smooth bowel walls are

present).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly arrangement

resembling a bag of popcorn more so than a bag of

sausages.

Impression: Ileus.

Case K: 9-day old male.

View Case K.

Interpretation of Case K

Gas Distribution: Poor distribution. Although gas is

present throughout most of the abdomen, its distribution

appears to be limited to just a few bowel segments.

Bowel Dilatation: Marked bowel distention though

difficult to determine small versus large bowel. The

bowel walls are smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple air-fluid levels mostly on

the left. Hair pins and candy canes are not present.

Arrangement of Loops: Not very helpful in this case.

The arrangement is best evaluated on the supine view

which is not obviously orderly or disorderly. In other

words, it is not easy to say whether this arrangement

resembles a bag of sausages or a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction based mainly on the gas

distribution and the degree of bowel dilatation. This is

not a normal abdominal series for a 9-day old. A

contrast enema demonstrated a transition zone

consistent with Hirschsprung's disease.

Case L: 12-month old female.

View Case L.

Interpretation of Case K

Gas Distribution: Poor distribution. Although gas is

present throughout most of the abdomen, its distribution

appears to be limited to just a few bowel segments.

Bowel Dilatation: Marked bowel distention though

difficult to determine small versus large bowel. The

bowel walls are smooth.

Air-Fluid Levels: Multiple air-fluid levels mostly on

the left. Hair pins and candy canes are not present.

Arrangement of Loops: Not very helpful in this case.

The arrangement is best evaluated on the supine view

which is not obviously orderly or disorderly. In other

words, it is not easy to say whether this arrangement

resembles a bag of sausages or a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction based mainly on the gas

distribution and the degree of bowel dilatation. This is

not a normal abdominal series for a 9-day old. A

contrast enema demonstrated a transition zone

consistent with Hirschsprung's disease.

Case L: 12-month old female.

View Case L.

Interpretation of Case L

Gas Distribution: Small areas of gas are present

throughout the entire abdomen. Many of the areas are

foamy suggesting the presence of excessive amounts

of stool.

Bowel Dilatation: Most of the bowel is not dilated.

There is a modest paucity of gas. There are two dilated

loops in the RLQ on the supine view (RLQ sentinel

loops).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Despite the

paucity of gas, the supine view resembles a bag of

popcorn more so than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. RLQ sentinel loops raise the

possibility of appendicitis.

Case M: 7-month old female.

View Case M.

Interpretation of Case L

Gas Distribution: Small areas of gas are present

throughout the entire abdomen. Many of the areas are

foamy suggesting the presence of excessive amounts

of stool.

Bowel Dilatation: Most of the bowel is not dilated.

There is a modest paucity of gas. There are two dilated

loops in the RLQ on the supine view (RLQ sentinel

loops).

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Despite the

paucity of gas, the supine view resembles a bag of

popcorn more so than a bag of sausages.

Impression: Ileus. RLQ sentinel loops raise the

possibility of appendicitis.

Case M: 7-month old female.

View Case M.

Interpretation of Case M

Gas Distribution: There is a definite paucity of gas

which is poorly distributed.

Bowel Dilatation: Nothing obvious.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Not a useful sign here

because of the paucity of gas.

Other comments: There is a "target sign" in the

right upper quadrant. The target sign is discussed in

detail in Case 2 of Volume 1. The target is faintly

visible as a doughnut shape (with the doughnut center

still present) in the right upper quadrant below the liver

(supine view). This is subtle. You may have to turn

down the room lights and adjust the contrast and

brightness on your monitor. This sign indicates the

presence of an intussusception. This radiograph also

demonstrates the "absent liver edge" sign (liver edge

not well defined in any view), which is also a sign of

intussusception (though less specific than the target

sign). If you have difficulty identifying the target and

liver edge findings in this radiograph, review Case 2 of

Volume 1 for other examples that are easier to identify.

Impression: Suggestive of an obstruction based

mainly on the paucity of gas. The target sign indicates

the presence of an intussusception. A barium enema

confirmed an intussusception.

Case N: 22-month old.

View Case N.

Interpretation of Case M

Gas Distribution: There is a definite paucity of gas

which is poorly distributed.

Bowel Dilatation: Nothing obvious.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Not a useful sign here

because of the paucity of gas.

Other comments: There is a "target sign" in the

right upper quadrant. The target sign is discussed in

detail in Case 2 of Volume 1. The target is faintly

visible as a doughnut shape (with the doughnut center

still present) in the right upper quadrant below the liver

(supine view). This is subtle. You may have to turn

down the room lights and adjust the contrast and

brightness on your monitor. This sign indicates the

presence of an intussusception. This radiograph also

demonstrates the "absent liver edge" sign (liver edge

not well defined in any view), which is also a sign of

intussusception (though less specific than the target

sign). If you have difficulty identifying the target and

liver edge findings in this radiograph, review Case 2 of

Volume 1 for other examples that are easier to identify.

Impression: Suggestive of an obstruction based

mainly on the paucity of gas. The target sign indicates

the presence of an intussusception. A barium enema

confirmed an intussusception.

Case N: 22-month old.

View Case N.

Interpretation of Case N

Gas Distribution: Good distribution except for one

portion in the LUQ. Although the upright view appears

to be somewhat gasless with most of the gas seen

localized to the upper abdomen only, the supine view

shows a better distribution of gas.

Bowel Dilatation: There are no dilated regions. The

haustra and plicae are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly.

Other Comments: The supine view demonstrates

"thumb printing" suggesting bowel wall edema such as

that seen in colitis. This is best seen in the LUQ

region (or left middle region) where the colon shows

thumb-shaped indentations into its lumen.

Impression: Ileus, colitis.

Case O: 11-month old male.

View Case O.

Interpretation of Case N

Gas Distribution: Good distribution except for one

portion in the LUQ. Although the upright view appears

to be somewhat gasless with most of the gas seen

localized to the upper abdomen only, the supine view

shows a better distribution of gas.

Bowel Dilatation: There are no dilated regions. The

haustra and plicae are well preserved.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly.

Other Comments: The supine view demonstrates

"thumb printing" suggesting bowel wall edema such as

that seen in colitis. This is best seen in the LUQ

region (or left middle region) where the colon shows

thumb-shaped indentations into its lumen.

Impression: Ileus, colitis.

Case O: 11-month old male.

View Case O.

Interpretation of Case O

Gas Distribution: Poorly distributed. Gas is

concentrated in the left upper quadrants in both the

supine and upright views.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated bowel

segments seen on the supine view. The bowel walls

are smooth and resemble sausages.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly. Note the two

dilated bowel segments on the supine view are stacked

on top of each other resembling a step ladder. Also,

this view clearly resembles a bag of sausages (only two

big ones), rather than a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction. A barium enema in this

case demonstrated intussusception.

Case P: 6-1/2 year old male.

View Case P.

Interpretation of Case O

Gas Distribution: Poorly distributed. Gas is

concentrated in the left upper quadrants in both the

supine and upright views.

Bowel Dilatation: There are two dilated bowel

segments seen on the supine view. The bowel walls

are smooth and resemble sausages.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Orderly. Note the two

dilated bowel segments on the supine view are stacked

on top of each other resembling a step ladder. Also,

this view clearly resembles a bag of sausages (only two

big ones), rather than a bag of popcorn.

Impression: Obstruction. A barium enema in this

case demonstrated intussusception.

Case P: 6-1/2 year old male.

View Case P.

Interpretation of Case P

Gas Distribution: Well distributed except for a

paucity of gas in the left lower quadrant.

Bowel Dilatation: The haustra and plicae are well

preserved. No smooth bowel walls are visible. The

caliber of the bowel is proportional to the normal bowel

size.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Does not

resemble a bag of sausages. Nor does it truly

resemble a bag of popcorn. However, there is no order

to the arrangement.

Impression: Ileus. There is a possible appendicolith

in the right lower quadrant (spherical density). This is

highly suggestive of acute appendicitis. This again

stresses the point, that an ileus is not necessarily

benign.

References

1. Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Radiology of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

second edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1986,

pp. 153-164.

2. Swischuk LE. The Alimentary Tract. In:

Radiology of the Newborn and Young Infant, second

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1980, pp.

487-490.

3. Kirks DR. The Gastrointestinal Tract. In:

Practical Pediatric and Diagnostic Radiology of Infants

and Children. Boston, Little, Brown and Company,

1984, pp. 551-553.

4. Parker BR. The Abdomen and Gastrointestinal

Tract. In: Silverman FN, Kuhn JP. Caffey's Pediatric

X-Ray Diagnosis, Ninth edition. St. Louis, Mosby,

1993, pp. 1059-1089.

5. Squire LF, Novelline RA. The Abdominal Plain

Film: Distended Stomach, Small Bowel, Colon, Free

Fluid and Free Air. In: Fundamentals of Radiology, 4th

edition. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press,

1988, pp. 194-205.

Interpretation of Case P

Gas Distribution: Well distributed except for a

paucity of gas in the left lower quadrant.

Bowel Dilatation: The haustra and plicae are well

preserved. No smooth bowel walls are visible. The

caliber of the bowel is proportional to the normal bowel

size.

Air-Fluid Levels: None.

Arrangement of Loops: Disorderly. Does not

resemble a bag of sausages. Nor does it truly

resemble a bag of popcorn. However, there is no order

to the arrangement.

Impression: Ileus. There is a possible appendicolith

in the right lower quadrant (spherical density). This is

highly suggestive of acute appendicitis. This again

stresses the point, that an ileus is not necessarily

benign.

References

1. Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Radiology of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

second edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1986,

pp. 153-164.

2. Swischuk LE. The Alimentary Tract. In:

Radiology of the Newborn and Young Infant, second

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1980, pp.

487-490.

3. Kirks DR. The Gastrointestinal Tract. In:

Practical Pediatric and Diagnostic Radiology of Infants

and Children. Boston, Little, Brown and Company,

1984, pp. 551-553.

4. Parker BR. The Abdomen and Gastrointestinal

Tract. In: Silverman FN, Kuhn JP. Caffey's Pediatric

X-Ray Diagnosis, Ninth edition. St. Louis, Mosby,

1993, pp. 1059-1089.

5. Squire LF, Novelline RA. The Abdominal Plain

Film: Distended Stomach, Small Bowel, Colon, Free

Fluid and Free Air. In: Fundamentals of Radiology, 4th

edition. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press,

1988, pp. 194-205.