Right-Sided Abdominal Pain in a 10-Year Old

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 5, Case 18

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

This is a 10-year old with an acute onset of sharp

constant epigastric pain without radiation. The pain is

worse when lying down and when ambulating. He is

unable to jump. He has had three loose stools without

blood, mucus, or foul odor. He has some nausea, but

no vomiting, dysuria, fever, or cold symptoms.

Exam: VS T36.7 (TM), P80, R18, BP 134/84,

oxygen saturation 100% in room air. He is in moderate

distress due to pain. He does not appear to be toxic.

Eyes normal. Ears normal. There is bilateral maxillary

sinus tenderness. Pharynx red with enlarged tonsils

(no exudates). Neck supple without adenopathy. Heart

regular without murmurs. Lungs clear. Abdomen flat,

guarding, moderate non-localized tenderness and

rebound. A Murphy's sign cannot be reliably elicited.

Bowel sounds are active. No masses. No hernias.

Testes are normal. No CVA tenderness. Extremities

with good pulses and perfusion. Strength good.

An abdominal series and laboratory studies are

ordered. He is given a dose of oral antacids.

View abdominal series [Supine view]

[Upright view]

[Upright view]

Laboratory studies: CBC WBC 7,000 with 24%

lymphs, 5% monos, and 71% segs. Hgb 13, Hct 34,

platelet count 329,000. Amylase 66. UA normal.

The abdominal series shows some dilated bowel.

The gas pattern is not distributed well. Most of the gas

is in the central abdomen. The flat view shows a small

opacification in the right upper quadrant. There may be

other small densities overlying the bowel gas inferiorly,

but this is not certain. The upright view shows a small

opacification on the right but it is located lower than the

opacity seen on the supine film. Either this is a different

lesion, or the opacification is mobile, and it moves

inferiorly with gravity.

Since this is not likely to be a vascular calcification in

a 10-year old, the differential includes urolithiasis,

cholelithiasis, or a high appendicolith.

View a close-up of the calcifications.

Laboratory studies: CBC WBC 7,000 with 24%

lymphs, 5% monos, and 71% segs. Hgb 13, Hct 34,

platelet count 329,000. Amylase 66. UA normal.

The abdominal series shows some dilated bowel.

The gas pattern is not distributed well. Most of the gas

is in the central abdomen. The flat view shows a small

opacification in the right upper quadrant. There may be

other small densities overlying the bowel gas inferiorly,

but this is not certain. The upright view shows a small

opacification on the right but it is located lower than the

opacity seen on the supine film. Either this is a different

lesion, or the opacification is mobile, and it moves

inferiorly with gravity.

Since this is not likely to be a vascular calcification in

a 10-year old, the differential includes urolithiasis,

cholelithiasis, or a high appendicolith.

View a close-up of the calcifications.

Following the antacid and a period of observation,

his abdominal pain subsides without other analgesics.

He does not have CVA tenderness and there is no

hematuria making urolithiasis unlikely. His exam is now

only positive for mild right upper quadrant tenderness

without rebound. His bowel sounds are active. He can

ambulate well and he tells the staff that he wants to go

home. He is given discharge instructions regarding

abdominal pain. He is instructed to see his physician in

the morning.

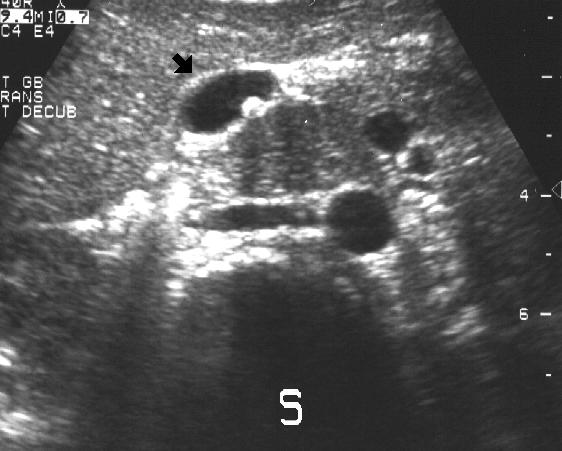

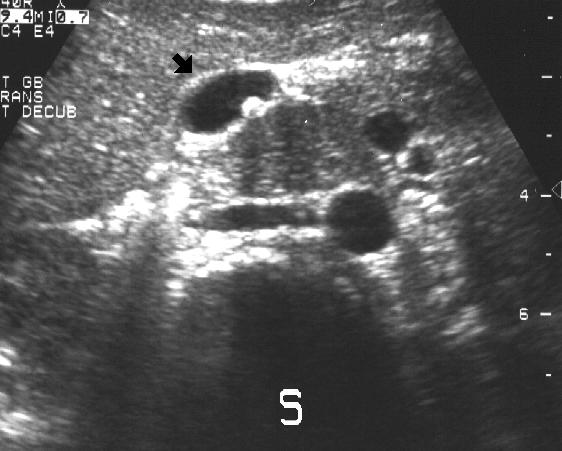

In a follow-up visit with his physician, he has

continued to improve. However, as a follow-up to

identify the cause of the right upper quadrant

opacifications, an abdominal ultrasound is performed.

View ultrasound.

Following the antacid and a period of observation,

his abdominal pain subsides without other analgesics.

He does not have CVA tenderness and there is no

hematuria making urolithiasis unlikely. His exam is now

only positive for mild right upper quadrant tenderness

without rebound. His bowel sounds are active. He can

ambulate well and he tells the staff that he wants to go

home. He is given discharge instructions regarding

abdominal pain. He is instructed to see his physician in

the morning.

In a follow-up visit with his physician, he has

continued to improve. However, as a follow-up to

identify the cause of the right upper quadrant

opacifications, an abdominal ultrasound is performed.

View ultrasound.

This ultrasound transducer is over the anterior

abdomen in the right upper quadrant. The liver is

shown here. The "S" is the spine. The black arrow

points to the gall bladder. A stone is seen in the gall

bladder in this view. Note the echo "shadow" cast by

the stone. Other views reveal other stones in the gall

bladder. There are no stones in the common duct.

Discussion

Gallstones in children are not felt to be common.

However, many of them are asymptomatic. While most

gallstones in children are classically associated with

hemolytic disease and hemoglobinopathies (hereditary

spherocytosis, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, etc.), an

increasing incidence of cholesterol stones have been

noted. It is now felt that cholesterol stones are more

common than pigment stones in children. Cholecystitis

and cholelithiasis are more common in childhood than is

generally appreciated. Other children at increased risk

include premature infants on furosemide and children

receiving parenteral nutrition.

The usual clinical presentation of cholecystitis and

cholelithiasis is often not present in children. Most

children present with non-specific abdominal pain. Liver

function studies may be normal. Plain film abdominal

radiographs may reveal calcifications, however, they

are often normal. Ultrasound is the easiest means of

making a definitive diagnosis of cholelithiasis. Acute

cholecystitis may require a bile duct flow study such as

a nuclear medicine excretion study. Cholecystitis may

sometimes occur without cholelithiasis (acalculous

cholecystitis).

Pediatric experience with newer therapeutic

approaches such as lithotripsy and bile acid stone

dissolution are lacking. Treatment has been

traditionally surgical, however, this may be evolving.

References

Holcomb GW. Gallbladder Disease. In: Welch KJ,

Randolph JG, Ravitch MM, etal (eds). Pediatric

Surgery, fourth edition. Year Book Medical Publishers,

Inc., Chicago, 1986, pp. 1060-1067.

Karrer FM, Lilly JR, Hall RJ. Biliary Tract Disorders

and Portal Hypertension. In: Ashcraft

KW, Holder TM. Pediatric Surgery, second edition.

W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1993, pp.

493-494.

Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Imaging of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

third edition. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994, pp.

254-258.

This ultrasound transducer is over the anterior

abdomen in the right upper quadrant. The liver is

shown here. The "S" is the spine. The black arrow

points to the gall bladder. A stone is seen in the gall

bladder in this view. Note the echo "shadow" cast by

the stone. Other views reveal other stones in the gall

bladder. There are no stones in the common duct.

Discussion

Gallstones in children are not felt to be common.

However, many of them are asymptomatic. While most

gallstones in children are classically associated with

hemolytic disease and hemoglobinopathies (hereditary

spherocytosis, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, etc.), an

increasing incidence of cholesterol stones have been

noted. It is now felt that cholesterol stones are more

common than pigment stones in children. Cholecystitis

and cholelithiasis are more common in childhood than is

generally appreciated. Other children at increased risk

include premature infants on furosemide and children

receiving parenteral nutrition.

The usual clinical presentation of cholecystitis and

cholelithiasis is often not present in children. Most

children present with non-specific abdominal pain. Liver

function studies may be normal. Plain film abdominal

radiographs may reveal calcifications, however, they

are often normal. Ultrasound is the easiest means of

making a definitive diagnosis of cholelithiasis. Acute

cholecystitis may require a bile duct flow study such as

a nuclear medicine excretion study. Cholecystitis may

sometimes occur without cholelithiasis (acalculous

cholecystitis).

Pediatric experience with newer therapeutic

approaches such as lithotripsy and bile acid stone

dissolution are lacking. Treatment has been

traditionally surgical, however, this may be evolving.

References

Holcomb GW. Gallbladder Disease. In: Welch KJ,

Randolph JG, Ravitch MM, etal (eds). Pediatric

Surgery, fourth edition. Year Book Medical Publishers,

Inc., Chicago, 1986, pp. 1060-1067.

Karrer FM, Lilly JR, Hall RJ. Biliary Tract Disorders

and Portal Hypertension. In: Ashcraft

KW, Holder TM. Pediatric Surgery, second edition.

W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1993, pp.

493-494.

Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Imaging of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

third edition. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994, pp.

254-258.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

[Upright view]

[Upright view]

Laboratory studies: CBC WBC 7,000 with 24%

lymphs, 5% monos, and 71% segs. Hgb 13, Hct 34,

platelet count 329,000. Amylase 66. UA normal.

The abdominal series shows some dilated bowel.

The gas pattern is not distributed well. Most of the gas

is in the central abdomen. The flat view shows a small

opacification in the right upper quadrant. There may be

other small densities overlying the bowel gas inferiorly,

but this is not certain. The upright view shows a small

opacification on the right but it is located lower than the

opacity seen on the supine film. Either this is a different

lesion, or the opacification is mobile, and it moves

inferiorly with gravity.

Since this is not likely to be a vascular calcification in

a 10-year old, the differential includes urolithiasis,

cholelithiasis, or a high appendicolith.

View a close-up of the calcifications.

Laboratory studies: CBC WBC 7,000 with 24%

lymphs, 5% monos, and 71% segs. Hgb 13, Hct 34,

platelet count 329,000. Amylase 66. UA normal.

The abdominal series shows some dilated bowel.

The gas pattern is not distributed well. Most of the gas

is in the central abdomen. The flat view shows a small

opacification in the right upper quadrant. There may be

other small densities overlying the bowel gas inferiorly,

but this is not certain. The upright view shows a small

opacification on the right but it is located lower than the

opacity seen on the supine film. Either this is a different

lesion, or the opacification is mobile, and it moves

inferiorly with gravity.

Since this is not likely to be a vascular calcification in

a 10-year old, the differential includes urolithiasis,

cholelithiasis, or a high appendicolith.

View a close-up of the calcifications.

Following the antacid and a period of observation,

his abdominal pain subsides without other analgesics.

He does not have CVA tenderness and there is no

hematuria making urolithiasis unlikely. His exam is now

only positive for mild right upper quadrant tenderness

without rebound. His bowel sounds are active. He can

ambulate well and he tells the staff that he wants to go

home. He is given discharge instructions regarding

abdominal pain. He is instructed to see his physician in

the morning.

In a follow-up visit with his physician, he has

continued to improve. However, as a follow-up to

identify the cause of the right upper quadrant

opacifications, an abdominal ultrasound is performed.

View ultrasound.

Following the antacid and a period of observation,

his abdominal pain subsides without other analgesics.

He does not have CVA tenderness and there is no

hematuria making urolithiasis unlikely. His exam is now

only positive for mild right upper quadrant tenderness

without rebound. His bowel sounds are active. He can

ambulate well and he tells the staff that he wants to go

home. He is given discharge instructions regarding

abdominal pain. He is instructed to see his physician in

the morning.

In a follow-up visit with his physician, he has

continued to improve. However, as a follow-up to

identify the cause of the right upper quadrant

opacifications, an abdominal ultrasound is performed.

View ultrasound.

This ultrasound transducer is over the anterior

abdomen in the right upper quadrant. The liver is

shown here. The "S" is the spine. The black arrow

points to the gall bladder. A stone is seen in the gall

bladder in this view. Note the echo "shadow" cast by

the stone. Other views reveal other stones in the gall

bladder. There are no stones in the common duct.

Discussion

Gallstones in children are not felt to be common.

However, many of them are asymptomatic. While most

gallstones in children are classically associated with

hemolytic disease and hemoglobinopathies (hereditary

spherocytosis, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, etc.), an

increasing incidence of cholesterol stones have been

noted. It is now felt that cholesterol stones are more

common than pigment stones in children. Cholecystitis

and cholelithiasis are more common in childhood than is

generally appreciated. Other children at increased risk

include premature infants on furosemide and children

receiving parenteral nutrition.

The usual clinical presentation of cholecystitis and

cholelithiasis is often not present in children. Most

children present with non-specific abdominal pain. Liver

function studies may be normal. Plain film abdominal

radiographs may reveal calcifications, however, they

are often normal. Ultrasound is the easiest means of

making a definitive diagnosis of cholelithiasis. Acute

cholecystitis may require a bile duct flow study such as

a nuclear medicine excretion study. Cholecystitis may

sometimes occur without cholelithiasis (acalculous

cholecystitis).

Pediatric experience with newer therapeutic

approaches such as lithotripsy and bile acid stone

dissolution are lacking. Treatment has been

traditionally surgical, however, this may be evolving.

References

Holcomb GW. Gallbladder Disease. In: Welch KJ,

Randolph JG, Ravitch MM, etal (eds). Pediatric

Surgery, fourth edition. Year Book Medical Publishers,

Inc., Chicago, 1986, pp. 1060-1067.

Karrer FM, Lilly JR, Hall RJ. Biliary Tract Disorders

and Portal Hypertension. In: Ashcraft

KW, Holder TM. Pediatric Surgery, second edition.

W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1993, pp.

493-494.

Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Imaging of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

third edition. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994, pp.

254-258.

This ultrasound transducer is over the anterior

abdomen in the right upper quadrant. The liver is

shown here. The "S" is the spine. The black arrow

points to the gall bladder. A stone is seen in the gall

bladder in this view. Note the echo "shadow" cast by

the stone. Other views reveal other stones in the gall

bladder. There are no stones in the common duct.

Discussion

Gallstones in children are not felt to be common.

However, many of them are asymptomatic. While most

gallstones in children are classically associated with

hemolytic disease and hemoglobinopathies (hereditary

spherocytosis, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, etc.), an

increasing incidence of cholesterol stones have been

noted. It is now felt that cholesterol stones are more

common than pigment stones in children. Cholecystitis

and cholelithiasis are more common in childhood than is

generally appreciated. Other children at increased risk

include premature infants on furosemide and children

receiving parenteral nutrition.

The usual clinical presentation of cholecystitis and

cholelithiasis is often not present in children. Most

children present with non-specific abdominal pain. Liver

function studies may be normal. Plain film abdominal

radiographs may reveal calcifications, however, they

are often normal. Ultrasound is the easiest means of

making a definitive diagnosis of cholelithiasis. Acute

cholecystitis may require a bile duct flow study such as

a nuclear medicine excretion study. Cholecystitis may

sometimes occur without cholelithiasis (acalculous

cholecystitis).

Pediatric experience with newer therapeutic

approaches such as lithotripsy and bile acid stone

dissolution are lacking. Treatment has been

traditionally surgical, however, this may be evolving.

References

Holcomb GW. Gallbladder Disease. In: Welch KJ,

Randolph JG, Ravitch MM, etal (eds). Pediatric

Surgery, fourth edition. Year Book Medical Publishers,

Inc., Chicago, 1986, pp. 1060-1067.

Karrer FM, Lilly JR, Hall RJ. Biliary Tract Disorders

and Portal Hypertension. In: Ashcraft

KW, Holder TM. Pediatric Surgery, second edition.

W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1993, pp.

493-494.

Swischuk LE. The Abdomen. In: Swischuk LE.

Emergency Imaging of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child,

third edition. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994, pp.

254-258.