Figure 1. The red reflex is visualized with an ophthalmoscope from a distance in a darkened room.

The editors and current author would like to thank and acknowledge the significant contribution of the previous author of this chapter from the 2004 first edition, Dr. Vince K. Yamashiroya. This current third edition chapter is a revision and update of the original author’s work.

This is a 6 month old baby girl who comes to your office for a well child examination. She has had no problems in the past with her eyes and according to her parents, she tracks well and reaches for objects. Her parents deny any crossing of the eyes when she looks at objects from a distance; however, her mother mentions that she had a lazy eye when she was a child and needed to be operated on.

Exam: Vital signs are normal for age. Her red reflex and corneal light reflex test are normal. Cover test is negative for strabismus. Her extraocular movements appear intact and she is able to follow objects 180 degrees.

You conclude that her eye examination is normal and reassure the mother. You schedule her next appointment when she is 9 months old or earlier if her mother notices a problem.

The examination of the eye is an essential part of an examination since disease or pathology of the eye can result in vision impairment or loss. Although there are diseases that are easily noticed, such as conjunctivitis, there are other conditions that are subtle. These conditions include leukocoria of retinoblastoma and strabismus that can lead to amblyopia. There are times that patients will come to us because of pain, itchiness, blurriness, redness, or discharge of the eye. As primary care physicians, we should be comfortable with the eye examination to be able to correctly diagnose, treat, or refer our patients for specialty care by an ophthalmologist. This chapter will focus on screening of the eye in the well child since some serious conditions can only be detected early enough through screening.

The basic anatomy of the eye is best understood by examining a diagram of the eye. The eye is made up of three layers. The outermost layer is the sclera, the white fibrous protective coating of the eye, and the cornea, which is the transparent continuation of the sclera. Deep to this is the uvea, which consists of the choroid, the ciliary body, and iris. The choroid is a vascular layer between the retina and sclera. The ciliary body, which produces aqueous humor, is on the sides of the lens that focusses the lens. Immediately anterior to the lens is the iris, which is a colored diaphragm that constricts or dilates, thereby regulating the amount of light entering through the lens. The innermost layer is the retina, which contains the rod and cones photoreceptors. The macula is a special part of the retina which is minimally vascular and is responsible for the most detailed vision. A pit in the center of the macula is the fovea, which corresponds to the central fixation of vision. Medial to the macula is the optic nerve, which transmits signals from the retina to the brain. There are two chambers within the globe, the anterior and posterior chamber, which are divided by the lens. The lens is flexible and functions to focus light onto the retina.. The anterior chamber is between the cornea and the lens, and is filled with the aqueous humor, which is a clear fluid. The posterior chamber contains the vitreous humor, which is a clear jelly filling. The conjunctiva is a mucus membrane that covers the anterior portion of the sclera (bulbar conjunctiva) and the inner part of the eyelids (palpebral conjunctiva). There are six extraocular muscles that move the eye. They are the four rectus muscles (superior, inferior, medial, and lateral) and the two oblique muscles (superior and inferior) which are innervated by cranial nerves 3, 4, and 6 (1).

The examination of the well child is primarily dependent on his or her age since infants and young children are less cooperative with the examination compared to older children. Screening for specific problems is essential at an early age to identify vision problems early.

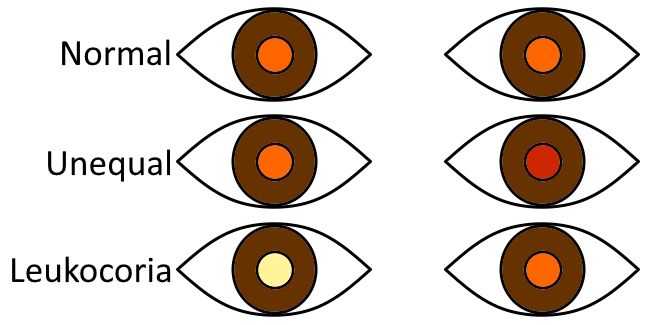

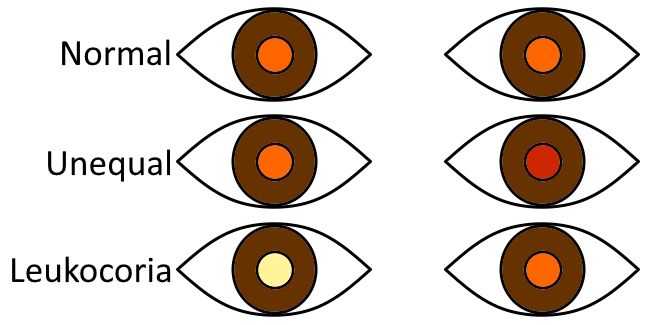

From birth to 6 months of age, screening tests include the red reflex, corneal light reflex, and external examination (2). The red reflex of an infant is visualized from a distance with the direct ophthalmoscope in a darkened room. Set the ophthalmoscope’s focus to 0 and view both eyes through the scope at the same time in order to compare the two (3). Many times, an infant's eyes are closed during the first several days of life. One trick to having them open their eyes is to gently swing them from a vertical to semi-upright position. Asymmetry or abnormalities in the red reflex in one or both eyes may be indicative of several problems, including refractive errors, corneal opacities and cataracts. A white is known as leukocoria which is suggestive of retinoblastoma. This white reflex is commonly detected by parents by chance during flash photography when they notice a "white eye" glow instead of the usual "red eye" glow. The red reflex is more of a peach/orange/red color. An absent red reflex appears dark gray or black. Sometimes parts of the red reflex are visible or focal opacities can be seen. Abnormal, asymmetric, or absent red reflexes or leukocoria warrant referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist.

Figure 1. The red reflex is visualized with an ophthalmoscope from a distance in a darkened room.

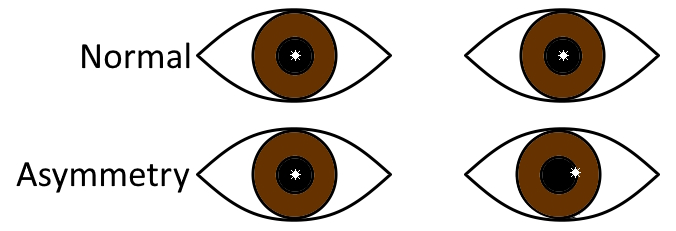

Another screening test is the corneal light reflex test in which the eyes are viewed with an ophthalmoscope or flashlight to see if the reflections off the corneas are symmetric. Asymmetry could signify strabismus (misalignment of the eyes) and warrants a referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist (2). Sometimes, the eyes might appear to be crossed, but this needs to be confirmed with asymmetry of the corneal light reflex.

Figure 2. The corneal light reflex should be symmetric in both eyes. Asymmetry is indicative of eye misalignment (strabismus).

Perform an external examination of the eyes and eyelids for symmetry of shape, position, and overall movement. Asymmetry may indicate proptosis, cranial nerve palsy, or lid masses (4). Note if the pupils are round and symmetrical. Irregularity could signify an iris coloboma, which is a "keyhole" shape (or other non-circular shape), caused by an embryological defect of closure of the eye. In a child with choanal atresia and ear anomalies, a coloboma (eye defect) can be part of CHARGE (coloboma and cranial nerve abnormalities, heart defects, atresia of the nasal choanae, restriction of growth and development, genital abnormalities, ear abnormalities) syndrome. Corneal size should be assessed since large corneas, together with excessive tearing and photophobia is a sign of infantile glaucoma.

From birth to 3 months of age, healthy infants can appear to have disconjugate or uneven gaze due to extraocular muscle weakness (5). Nystagmus, is abnormal at any age. By the age of 6 weeks, infants should respond to the examiner's face and should be able to fix and follow an object by the age of 2 months. If a strong binocular fix and follow is not seen by three months of age, referral to ophthalmology is recommended (2).

Subconjunctival in neonates can occur with birth trauma, and will resolve on its own. The color of the sclera should also be noted, since a blue sclera, in addition to multiple bone fractures can signify osteogenesis imperfecta. Also, a yellow or icteric sclera is seen in jaundiced babies. At times, there is mucoid discharge around the medial canthus of the eye, which can be due to nasolacrimal duct obstruction. This problem either resolves spontaneously or parents can be instructed to massage the duct which should result in resolution by 1 year of age. However, if it continues past a year, then referral to ophthalmology is indicated to assess whether the nasolacrimal ducts should be probed and/or dilated.

From 6 months to 4 years of age, the cover test can be used to assess strabismus and vision, as it is more accurate than the corneal light reflection test when testing for eye misalignment (2). This test is performed by covering one of the eyes and observing for movement (or a shift) in the contralateral eye, and when uncovered, observing for movement in the ipsilateral eye. This is best done by having the child focus on something at a distance (such as a light), holding the head still with your hand, and then covering and uncovering one eye while observing for movement, then repeating this for the other eye. No eye movement of either eye indicates normal eye alignment. The parents or caretakers can be questioned if they notice one eye being crossed or crooked when the child looks at something. This is sometimes due to pseudostrabismus in a child with epicanthal folds. This can usually be distinguished from abnormal with the corneal light reflex, but if there is any doubt, a referral to ophthalmology can be helpful (5).

One complication of uncorrected strabismus is amblyopia. While strabismus refers to the physical misalignment of the eyes, amblyopia refers to reduced visual acuity that results in the brain favoring one eye over the other (6). The brain normally develops binocular vision (stereopsis) to perceive and process our surroundings in 3 dimensions. Each eye views a slightly different image and our brain merges these to provide depth perception (7). Patients presenting with even mild forms of amblyopia have reduced degrees of steropsis since less visual information is being processed and integrated from one of the eyes (7).

From 4 years of age and onward, the eye exam can be performed in a similar fashion as with adults. Eye charts commonly used for children are the HOTV letters chart, the Sloan chart (capital alphabets), and the Lea symbols® (house, apple, square, circle) chart. Other charts known as the Allen figures, sailboat chart, lighthouse chart, etc., utilize optotypes (images) that have not been as well validated to be used for visual acuity testing in children (2). At 3 years of age, average visual acuity is 20/30 which improves to 20/20 at the age of 6 to 8 years (8). Referral to an ophthalmologist is indicated if a 3 to 4 year old child has vision that is 20/50 vision or worse or/and if a 4 to 5 year old child has 20/40 vision or worse (5).

Fundoscopy can be done, even in younger children. One method is to remain stationary while viewing the eye, and have the child move their eye on their own, asking them to look at different body parts to examine the different areas of the retina (9). As you move closer, ensure that the red reflex is equal in all four quadrants, visualize the optic disk and then look for the bright fovea reflection by telling the child to look at the light.

There are instrument-based screening techniques which include photoscreening and autorefraction machinery. These techniques are useful for assessing amblyopia and reduced-vision risk factors in children 1 to 5 years old. These tests can be performed in primary care but are more routine in an ophthalmologist’s office. Instrument-based vision-screening can be useful for younger children and those with developmental delays (2).

Questions

1. What is the differential diagnosis of an absent pupillary light reflex (red reflex)?

2. What condition causes leukocoria?

3. A parent is worried that her Asian baby has crooked eyes. How would you assess whether this is pseudostrabismus?

4. What is one way you can look at the fundus in the uncooperative child?

5. What is the difference between strabismus and amblyopia?

References

1. Riordan-Eva P. Chapter 1. Anatomy & Embryology of the Eye. In: Riordan-Eva P, Augsburger JJ (eds). Vaughan & Asbury's General Ophthalmology, 19th edition. McGraw Hill, New York. 2018. pp:1-35.

2. Hutchinson AK, Morse CL, Hercinovic A, et al, American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus Panel. Pediatric Eye Evaluations Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology. 2023;130(3):P222-P270. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.10.030

3. Donahue SP, Baker CN. Procedures for the Evaluation of the Visual System by Pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):10.1542/peds.2015-3597. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3597

4. Wan MJ, VanderVeen DK. Eye disorders in newborn infants (excluding retinopathy of prematurity). Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100(3):F264-F269. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306215

5. Martin EF. Performing pediatric eye exams in primary care. Nurse Pract. 2017;42(8):41-47. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000520791.94940

6. Repka MX. Chapter 74. Amblyopia: the basics, the questions, and the practical management. In: Lyons CJ, Lambert SR (eds). Taylor and Hoyt's Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 6th edition. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2023. pp:838-845.

7. Birch EE, O’Connor AR. Chapter 73. Binocular Vision. In: Lyons CJ, Lambert SR (eds). Taylor and Hoyt's Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 6th edition. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2023. pp:830-837.

8. Birch, EE, Kelly KR. Chapter 3. Normal and Abnormal Visual Development. In: Lyons CJ, Lambert SR (eds). Taylor and Hoyt's Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 6th edition. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2023. pp:32-41

9. LaRoche GR. Chapter 5. Examination, history, and special tests in pediatric ophthalmology. In: Lyons CJ, Lambert SR (eds). Taylor and Hoyt's Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 6th edition. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2023. pp:52-62.

Answers to questions

1. Cataracts, retinal detachment, and other pathology that is obscuring the vitreous or aqueous clarity.

2. Retinoblastoma.

3. Performing a cover test and corneal light test.

4. By being patient, looking at the child's red reflex in all four quadrants in a stationary position from about 12 inches (30 cm) away, and as you move closer, viewing the optic disk as it passes by, and lastly the fovea by telling the child to look directly at your magic light. Despite these maneuvers, it can still be very difficult.

5. Strabismus is eye misalignment. Amblyopia results from strabismus that is not corrected. Due to eye misalignment, the brain suppresses vision from one eye. Without correction, this can result in loss of vision from one of the eyes. With correction, amblyopia is prevented, or its severity is reduced.