Tachypnea and Abdominal Pain

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 2, Case 5

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Lynette L. Young, MD

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

This is a 6 year old male who was referred from a

rural ED for fever and possible pneumonia. He was

well until three days ago when he was stung by a bee

on his right forearm. He developed a moderate local

reaction with edema and erythema. He saw his primary

care physician the next day at which time he also

complained of chest pain. Chest radiographs were

obtained that day and they were negative. The next

evening (yesterday), he developed fever and worsening

of the swelling and erythema of his right forearm. He

was seen at a rural ED. Cellulitis and a hypersensitivity

reaction were considered. He was placed on oral

cephalexin and acetaminophen with codeine. He took

two doses of cephalexin. He returned to the rural ED in

the morning (today) because of abdominal pain. Chest

radiographs were repeated. This was interpreted as

showing a possible right lower lobe infiltrate. A CBC at

that time showed: WBC 20.4, 67% segs and 18%

bands.

Exam on arrival: VS T38.5 (oral), P145, R44, BP

140/89, oxygen saturation 96% (room air). He was

obese, crying, agitated, and uncooperative, making

examination difficult. HEENT exam significant for

slightly dry oral mucosa. Neck supple. Heart regular,

tachycardic, without murmurs or gallops. Lungs coarse

breath sounds with rhonchi in both bases. Abdominal

guarding noted throughout with tenderness. Bowel

sounds were hypoactive. His right arm was diffusely

indurated and erythematous (difficult to distinguish

cellulitis from hypersensitivity).

He was given a fleets enema for suspected

constipation. He passed large amounts of stool and

seemed to be better in that he was less agitated and

more cooperative. He was noted to be grunting at

times. His abdomen was still tender. More blood

studies were drawn. Radiographs of his chest and

abdomen were obtained.

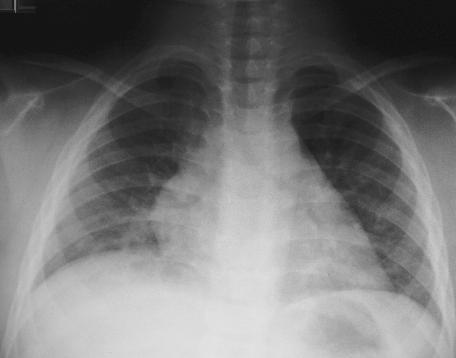

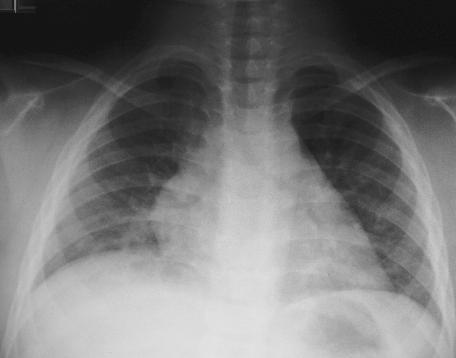

View CXR: PA view.

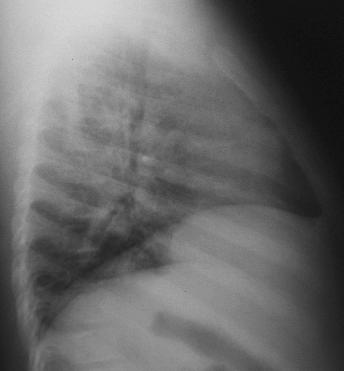

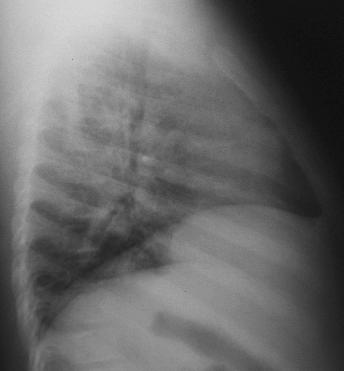

View CXR: Lateral view.

View CXR: Lateral view.

View Abdominal Series: Upright view.

View Abdominal Series: Upright view.

View Abdominal Series: Supine view.

View Abdominal Series: Supine view.

Although there some subtle abnormalities on his

CXR, there were no definite abnormalities to account

for his grunting and abdominal pain. There were some

possible central infiltrates and the right hemidiaphragm

appeared to be possibly elevated. The inspiratory effort

shown on the film was poor. This was also noted on

the CXR from the rural ED. His abdominal radiographs

showed some bowel distention, but consistent with an

ileus and not a bowel obstruction.

Laboratory results: CBC WBC 33.6, 1 meta, 29

bands, 63 segs, 5 lymphs, 2 monos, Hgb 13.1, Hct

39.0, platelet count 310,000. Na 136, K 4.0, Cl 102,

Bicarb 21, glucose 142. UA SG 1.031, 0-2 WBC,

3-5 RBC.

An abdominal ultrasound was performed looking for

an intra-abdominal abscess. This study showed a

suspicious right lower quadrant mass, but it was unable

to define it further. A surgical consultation was

obtained. The likelihood of acute appendicitis was felt

to be low. A CT scan of the abdomen was obtained.

This study was unremarkable except for a view of the

upper abdomen.

View CT scan.

Although there some subtle abnormalities on his

CXR, there were no definite abnormalities to account

for his grunting and abdominal pain. There were some

possible central infiltrates and the right hemidiaphragm

appeared to be possibly elevated. The inspiratory effort

shown on the film was poor. This was also noted on

the CXR from the rural ED. His abdominal radiographs

showed some bowel distention, but consistent with an

ileus and not a bowel obstruction.

Laboratory results: CBC WBC 33.6, 1 meta, 29

bands, 63 segs, 5 lymphs, 2 monos, Hgb 13.1, Hct

39.0, platelet count 310,000. Na 136, K 4.0, Cl 102,

Bicarb 21, glucose 142. UA SG 1.031, 0-2 WBC,

3-5 RBC.

An abdominal ultrasound was performed looking for

an intra-abdominal abscess. This study showed a

suspicious right lower quadrant mass, but it was unable

to define it further. A surgical consultation was

obtained. The likelihood of acute appendicitis was felt

to be low. A CT scan of the abdomen was obtained.

This study was unremarkable except for a view of the

upper abdomen.

View CT scan.

This CT cut is through the upper abdomen. It shows

the liver, parts of the diaphragm, and the lower portions

of the lungs. Pulmonary infiltrates are noted in the

posterior portion of the right lower lobe. Note the

pleural effusion adjacent to the infiltrates (arrows). He

was given IV ceftriaxone and hospitalization was

arranged.

Six hours after leaving the ED, house officers

ordered a follow-up CXR (13 hours after the ED CXR,

and 8 hours after the CT scan).

View follow-up CXR.

This CT cut is through the upper abdomen. It shows

the liver, parts of the diaphragm, and the lower portions

of the lungs. Pulmonary infiltrates are noted in the

posterior portion of the right lower lobe. Note the

pleural effusion adjacent to the infiltrates (arrows). He

was given IV ceftriaxone and hospitalization was

arranged.

Six hours after leaving the ED, house officers

ordered a follow-up CXR (13 hours after the ED CXR,

and 8 hours after the CT scan).

View follow-up CXR.

This CXR shows a large right pleural effusion. This

is a significant change over the 13 hour period since the

previous CXR suggesting a rapidly progressive

pneumonia. This is highly suspicious for a

staphylococcal pneumonia. The source of the staph

was suspected to be the cellulitis on his arm. The

pleural effusion worsened, at which time it was drained

through a tube thoracostomy. Gram stain of the fluid

revealed gram positive cocci. Cell counts 50,000

RBC's, 29,000 WBC's, 70% segs, 18% bands. Protein

5.4 grams/dl, pH 7.0, glucose 8 mg/dl. He required a

second chest tube to drain a loculated empyema.

Other than this, he did remarkably well. He did not

develop any pneumatoceles or a pneumothorax. He

was discharged after 6 weeks of IV antibiotics.

Teaching Points and Discussion

Staphylococcal pneumonia is rapidly progressive in

all age groups. This is a serious pulmonary infection

that is associated with significant morbidity and a high

potential for death.

There are two main forms of staphylococcal

pneumonia. Primary pneumonia is caused by direct

inoculation through the respiratory tract. Secondary or

metastatic hematogenous lung infection is due to

bacteremic seeding of the lung during the course of

endocarditis or septicemia associated with infection at

other sites. It is not unusual to see severe impetigo

associated with staphylococcal pneumonia.

Primary staphylococcal pneumonia is a disease of

infancy and childhood with three-quarters of the cases

involving patients less than one-year old. Predisposing

factors include cystic fibrosis, chronic lung disease,

leukemia, preexisting skin infection, and viral respiratory

infection (measles, influenza, adenovirus).

The patients with staphylococcal pneumonia may

present with fever, lethargy, severe respiratory distress

(tachypnea, grunting, retractions, cyanosis), and

gastrointestinal disturbances (anorexia, vomiting,

abdominal distention). About 75% of patients present

with fever, cough, and dyspnea. The rapid progression

of clinical symptoms is characteristic of staphylococcal

pneumonia.

Chest radiographs in the early stage of

staphylococcal pneumonia may be normal or show a

minimal focal infiltrate. In general, there is a rapid

progression of radiographic findings over just a few

hours. The segmental bronchopneumonia pattern is

usually unilateral and then expands to involve other

lobes. In the case of our patient here, he presented

with abdominal pain and tachypnea. A small infiltrate

was noted which progressed to a large pleural effusion

over a few hours.

About 71% of pneumonias due to Staph aureus

have associated pleural effusions. The effusion is on

the right in 65%, on the left in 15% and bilateral 20% of

the time. This frequently progresses to an empyema.

Ultrasound or CT is often helpful in locating the

loculated fluid.

A pulmonary pneumatocele is a frequent

complication of staphylococcal pneumonia with an

incidence of greater than 85%. There are usually

multiple pneumatoceles which vary in size.

Pneumatoceles are believed to be caused by a partial

airway obstruction by intraluminal exudate or a

peribronchial abscess.

A lung abscess is another complication of

staphylococcal pneumonia. An abscess is a relatively

thick-walled cavity, in contrast to a pneumatocele which

is usually a thin-walled radiolucent area. Fluid levels

may be present in both pneumatoceles and abscesses.

The incidence of pneumothorax associated with

staphylococcal pneumonia is between 40% to 60%. A

pneumothorax may result from a pneumatocele rupture

or formation of a bronchopleural fistula (localized

bronchial wall necrosis). A pyopneumothorax

(pneumothorax + empyema) is highly suggestive of

staphylococcal pneumonia.

Empyemas require drainage with large bore tube

thoracostomies. The empyema is often rapidly

progressive, which leads to compression of the lung

and respiratory failure unless the empyema is drained.

It is likely to reaccumulate following a thoracentesis.

Chest tube thoracostomy also has the benefit of

maintaining lung expansion if a pneumothorax

develops.

A pathogen is recovered from patients with

pneumonia and effusions about 76% of the time. Of

these, pleural fluid cultures are positive in 86% and

blood cultures are positive in 10%.

Although antibiotic coverage with anti-staphylococcal

penicillins (e.g., oxacillin) or first generation

cephalosporins (e.g.. cefazolin) is usually sufficient,

there is a substantial rate of resistance to these drugs.

Methicillin resistant staph aureus will usually be

cephalosporin resistant as well. Vancomycin should be

added to the anti-staphylococcal antibiotic regimen until

sensitivities of the organism are determined.

Complications of staphylococcal pneumonia include

endocarditis, purulent pericarditis, osteomyelitis, deep

tissue abscess, septic arthritis, and meningitis.

References

Chartrand SA, McCracken GH. Staphylococcal

pneumonia in infants and children. Ped Infect Dis

1982;1:19-23.

Forbes GB, Emerson GL. Staphylococcal

pneumonia and empyema. Pediat Clin N Amer

1957;4:215-229.

Melish ME. Staphylococcal Infections. In: Feigin

RD, Cherry JD (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Infectious

Diseases, 2nd edition, 1987, Philadelphia, WB

Saunders Company, pp. 1260-1292.

This CXR shows a large right pleural effusion. This

is a significant change over the 13 hour period since the

previous CXR suggesting a rapidly progressive

pneumonia. This is highly suspicious for a

staphylococcal pneumonia. The source of the staph

was suspected to be the cellulitis on his arm. The

pleural effusion worsened, at which time it was drained

through a tube thoracostomy. Gram stain of the fluid

revealed gram positive cocci. Cell counts 50,000

RBC's, 29,000 WBC's, 70% segs, 18% bands. Protein

5.4 grams/dl, pH 7.0, glucose 8 mg/dl. He required a

second chest tube to drain a loculated empyema.

Other than this, he did remarkably well. He did not

develop any pneumatoceles or a pneumothorax. He

was discharged after 6 weeks of IV antibiotics.

Teaching Points and Discussion

Staphylococcal pneumonia is rapidly progressive in

all age groups. This is a serious pulmonary infection

that is associated with significant morbidity and a high

potential for death.

There are two main forms of staphylococcal

pneumonia. Primary pneumonia is caused by direct

inoculation through the respiratory tract. Secondary or

metastatic hematogenous lung infection is due to

bacteremic seeding of the lung during the course of

endocarditis or septicemia associated with infection at

other sites. It is not unusual to see severe impetigo

associated with staphylococcal pneumonia.

Primary staphylococcal pneumonia is a disease of

infancy and childhood with three-quarters of the cases

involving patients less than one-year old. Predisposing

factors include cystic fibrosis, chronic lung disease,

leukemia, preexisting skin infection, and viral respiratory

infection (measles, influenza, adenovirus).

The patients with staphylococcal pneumonia may

present with fever, lethargy, severe respiratory distress

(tachypnea, grunting, retractions, cyanosis), and

gastrointestinal disturbances (anorexia, vomiting,

abdominal distention). About 75% of patients present

with fever, cough, and dyspnea. The rapid progression

of clinical symptoms is characteristic of staphylococcal

pneumonia.

Chest radiographs in the early stage of

staphylococcal pneumonia may be normal or show a

minimal focal infiltrate. In general, there is a rapid

progression of radiographic findings over just a few

hours. The segmental bronchopneumonia pattern is

usually unilateral and then expands to involve other

lobes. In the case of our patient here, he presented

with abdominal pain and tachypnea. A small infiltrate

was noted which progressed to a large pleural effusion

over a few hours.

About 71% of pneumonias due to Staph aureus

have associated pleural effusions. The effusion is on

the right in 65%, on the left in 15% and bilateral 20% of

the time. This frequently progresses to an empyema.

Ultrasound or CT is often helpful in locating the

loculated fluid.

A pulmonary pneumatocele is a frequent

complication of staphylococcal pneumonia with an

incidence of greater than 85%. There are usually

multiple pneumatoceles which vary in size.

Pneumatoceles are believed to be caused by a partial

airway obstruction by intraluminal exudate or a

peribronchial abscess.

A lung abscess is another complication of

staphylococcal pneumonia. An abscess is a relatively

thick-walled cavity, in contrast to a pneumatocele which

is usually a thin-walled radiolucent area. Fluid levels

may be present in both pneumatoceles and abscesses.

The incidence of pneumothorax associated with

staphylococcal pneumonia is between 40% to 60%. A

pneumothorax may result from a pneumatocele rupture

or formation of a bronchopleural fistula (localized

bronchial wall necrosis). A pyopneumothorax

(pneumothorax + empyema) is highly suggestive of

staphylococcal pneumonia.

Empyemas require drainage with large bore tube

thoracostomies. The empyema is often rapidly

progressive, which leads to compression of the lung

and respiratory failure unless the empyema is drained.

It is likely to reaccumulate following a thoracentesis.

Chest tube thoracostomy also has the benefit of

maintaining lung expansion if a pneumothorax

develops.

A pathogen is recovered from patients with

pneumonia and effusions about 76% of the time. Of

these, pleural fluid cultures are positive in 86% and

blood cultures are positive in 10%.

Although antibiotic coverage with anti-staphylococcal

penicillins (e.g., oxacillin) or first generation

cephalosporins (e.g.. cefazolin) is usually sufficient,

there is a substantial rate of resistance to these drugs.

Methicillin resistant staph aureus will usually be

cephalosporin resistant as well. Vancomycin should be

added to the anti-staphylococcal antibiotic regimen until

sensitivities of the organism are determined.

Complications of staphylococcal pneumonia include

endocarditis, purulent pericarditis, osteomyelitis, deep

tissue abscess, septic arthritis, and meningitis.

References

Chartrand SA, McCracken GH. Staphylococcal

pneumonia in infants and children. Ped Infect Dis

1982;1:19-23.

Forbes GB, Emerson GL. Staphylococcal

pneumonia and empyema. Pediat Clin N Amer

1957;4:215-229.

Melish ME. Staphylococcal Infections. In: Feigin

RD, Cherry JD (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Infectious

Diseases, 2nd edition, 1987, Philadelphia, WB

Saunders Company, pp. 1260-1292.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

View CXR: Lateral view.

View CXR: Lateral view.

View Abdominal Series: Upright view.

View Abdominal Series: Upright view.

View Abdominal Series: Supine view.

View Abdominal Series: Supine view.

Although there some subtle abnormalities on his

CXR, there were no definite abnormalities to account

for his grunting and abdominal pain. There were some

possible central infiltrates and the right hemidiaphragm

appeared to be possibly elevated. The inspiratory effort

shown on the film was poor. This was also noted on

the CXR from the rural ED. His abdominal radiographs

showed some bowel distention, but consistent with an

ileus and not a bowel obstruction.

Laboratory results: CBC WBC 33.6, 1 meta, 29

bands, 63 segs, 5 lymphs, 2 monos, Hgb 13.1, Hct

39.0, platelet count 310,000. Na 136, K 4.0, Cl 102,

Bicarb 21, glucose 142. UA SG 1.031, 0-2 WBC,

3-5 RBC.

An abdominal ultrasound was performed looking for

an intra-abdominal abscess. This study showed a

suspicious right lower quadrant mass, but it was unable

to define it further. A surgical consultation was

obtained. The likelihood of acute appendicitis was felt

to be low. A CT scan of the abdomen was obtained.

This study was unremarkable except for a view of the

upper abdomen.

View CT scan.

Although there some subtle abnormalities on his

CXR, there were no definite abnormalities to account

for his grunting and abdominal pain. There were some

possible central infiltrates and the right hemidiaphragm

appeared to be possibly elevated. The inspiratory effort

shown on the film was poor. This was also noted on

the CXR from the rural ED. His abdominal radiographs

showed some bowel distention, but consistent with an

ileus and not a bowel obstruction.

Laboratory results: CBC WBC 33.6, 1 meta, 29

bands, 63 segs, 5 lymphs, 2 monos, Hgb 13.1, Hct

39.0, platelet count 310,000. Na 136, K 4.0, Cl 102,

Bicarb 21, glucose 142. UA SG 1.031, 0-2 WBC,

3-5 RBC.

An abdominal ultrasound was performed looking for

an intra-abdominal abscess. This study showed a

suspicious right lower quadrant mass, but it was unable

to define it further. A surgical consultation was

obtained. The likelihood of acute appendicitis was felt

to be low. A CT scan of the abdomen was obtained.

This study was unremarkable except for a view of the

upper abdomen.

View CT scan.

This CT cut is through the upper abdomen. It shows

the liver, parts of the diaphragm, and the lower portions

of the lungs. Pulmonary infiltrates are noted in the

posterior portion of the right lower lobe. Note the

pleural effusion adjacent to the infiltrates (arrows). He

was given IV ceftriaxone and hospitalization was

arranged.

Six hours after leaving the ED, house officers

ordered a follow-up CXR (13 hours after the ED CXR,

and 8 hours after the CT scan).

View follow-up CXR.

This CT cut is through the upper abdomen. It shows

the liver, parts of the diaphragm, and the lower portions

of the lungs. Pulmonary infiltrates are noted in the

posterior portion of the right lower lobe. Note the

pleural effusion adjacent to the infiltrates (arrows). He

was given IV ceftriaxone and hospitalization was

arranged.

Six hours after leaving the ED, house officers

ordered a follow-up CXR (13 hours after the ED CXR,

and 8 hours after the CT scan).

View follow-up CXR.

This CXR shows a large right pleural effusion. This

is a significant change over the 13 hour period since the

previous CXR suggesting a rapidly progressive

pneumonia. This is highly suspicious for a

staphylococcal pneumonia. The source of the staph

was suspected to be the cellulitis on his arm. The

pleural effusion worsened, at which time it was drained

through a tube thoracostomy. Gram stain of the fluid

revealed gram positive cocci. Cell counts 50,000

RBC's, 29,000 WBC's, 70% segs, 18% bands. Protein

5.4 grams/dl, pH 7.0, glucose 8 mg/dl. He required a

second chest tube to drain a loculated empyema.

Other than this, he did remarkably well. He did not

develop any pneumatoceles or a pneumothorax. He

was discharged after 6 weeks of IV antibiotics.

Teaching Points and Discussion

Staphylococcal pneumonia is rapidly progressive in

all age groups. This is a serious pulmonary infection

that is associated with significant morbidity and a high

potential for death.

There are two main forms of staphylococcal

pneumonia. Primary pneumonia is caused by direct

inoculation through the respiratory tract. Secondary or

metastatic hematogenous lung infection is due to

bacteremic seeding of the lung during the course of

endocarditis or septicemia associated with infection at

other sites. It is not unusual to see severe impetigo

associated with staphylococcal pneumonia.

Primary staphylococcal pneumonia is a disease of

infancy and childhood with three-quarters of the cases

involving patients less than one-year old. Predisposing

factors include cystic fibrosis, chronic lung disease,

leukemia, preexisting skin infection, and viral respiratory

infection (measles, influenza, adenovirus).

The patients with staphylococcal pneumonia may

present with fever, lethargy, severe respiratory distress

(tachypnea, grunting, retractions, cyanosis), and

gastrointestinal disturbances (anorexia, vomiting,

abdominal distention). About 75% of patients present

with fever, cough, and dyspnea. The rapid progression

of clinical symptoms is characteristic of staphylococcal

pneumonia.

Chest radiographs in the early stage of

staphylococcal pneumonia may be normal or show a

minimal focal infiltrate. In general, there is a rapid

progression of radiographic findings over just a few

hours. The segmental bronchopneumonia pattern is

usually unilateral and then expands to involve other

lobes. In the case of our patient here, he presented

with abdominal pain and tachypnea. A small infiltrate

was noted which progressed to a large pleural effusion

over a few hours.

About 71% of pneumonias due to Staph aureus

have associated pleural effusions. The effusion is on

the right in 65%, on the left in 15% and bilateral 20% of

the time. This frequently progresses to an empyema.

Ultrasound or CT is often helpful in locating the

loculated fluid.

A pulmonary pneumatocele is a frequent

complication of staphylococcal pneumonia with an

incidence of greater than 85%. There are usually

multiple pneumatoceles which vary in size.

Pneumatoceles are believed to be caused by a partial

airway obstruction by intraluminal exudate or a

peribronchial abscess.

A lung abscess is another complication of

staphylococcal pneumonia. An abscess is a relatively

thick-walled cavity, in contrast to a pneumatocele which

is usually a thin-walled radiolucent area. Fluid levels

may be present in both pneumatoceles and abscesses.

The incidence of pneumothorax associated with

staphylococcal pneumonia is between 40% to 60%. A

pneumothorax may result from a pneumatocele rupture

or formation of a bronchopleural fistula (localized

bronchial wall necrosis). A pyopneumothorax

(pneumothorax + empyema) is highly suggestive of

staphylococcal pneumonia.

Empyemas require drainage with large bore tube

thoracostomies. The empyema is often rapidly

progressive, which leads to compression of the lung

and respiratory failure unless the empyema is drained.

It is likely to reaccumulate following a thoracentesis.

Chest tube thoracostomy also has the benefit of

maintaining lung expansion if a pneumothorax

develops.

A pathogen is recovered from patients with

pneumonia and effusions about 76% of the time. Of

these, pleural fluid cultures are positive in 86% and

blood cultures are positive in 10%.

Although antibiotic coverage with anti-staphylococcal

penicillins (e.g., oxacillin) or first generation

cephalosporins (e.g.. cefazolin) is usually sufficient,

there is a substantial rate of resistance to these drugs.

Methicillin resistant staph aureus will usually be

cephalosporin resistant as well. Vancomycin should be

added to the anti-staphylococcal antibiotic regimen until

sensitivities of the organism are determined.

Complications of staphylococcal pneumonia include

endocarditis, purulent pericarditis, osteomyelitis, deep

tissue abscess, septic arthritis, and meningitis.

References

Chartrand SA, McCracken GH. Staphylococcal

pneumonia in infants and children. Ped Infect Dis

1982;1:19-23.

Forbes GB, Emerson GL. Staphylococcal

pneumonia and empyema. Pediat Clin N Amer

1957;4:215-229.

Melish ME. Staphylococcal Infections. In: Feigin

RD, Cherry JD (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Infectious

Diseases, 2nd edition, 1987, Philadelphia, WB

Saunders Company, pp. 1260-1292.

This CXR shows a large right pleural effusion. This

is a significant change over the 13 hour period since the

previous CXR suggesting a rapidly progressive

pneumonia. This is highly suspicious for a

staphylococcal pneumonia. The source of the staph

was suspected to be the cellulitis on his arm. The

pleural effusion worsened, at which time it was drained

through a tube thoracostomy. Gram stain of the fluid

revealed gram positive cocci. Cell counts 50,000

RBC's, 29,000 WBC's, 70% segs, 18% bands. Protein

5.4 grams/dl, pH 7.0, glucose 8 mg/dl. He required a

second chest tube to drain a loculated empyema.

Other than this, he did remarkably well. He did not

develop any pneumatoceles or a pneumothorax. He

was discharged after 6 weeks of IV antibiotics.

Teaching Points and Discussion

Staphylococcal pneumonia is rapidly progressive in

all age groups. This is a serious pulmonary infection

that is associated with significant morbidity and a high

potential for death.

There are two main forms of staphylococcal

pneumonia. Primary pneumonia is caused by direct

inoculation through the respiratory tract. Secondary or

metastatic hematogenous lung infection is due to

bacteremic seeding of the lung during the course of

endocarditis or septicemia associated with infection at

other sites. It is not unusual to see severe impetigo

associated with staphylococcal pneumonia.

Primary staphylococcal pneumonia is a disease of

infancy and childhood with three-quarters of the cases

involving patients less than one-year old. Predisposing

factors include cystic fibrosis, chronic lung disease,

leukemia, preexisting skin infection, and viral respiratory

infection (measles, influenza, adenovirus).

The patients with staphylococcal pneumonia may

present with fever, lethargy, severe respiratory distress

(tachypnea, grunting, retractions, cyanosis), and

gastrointestinal disturbances (anorexia, vomiting,

abdominal distention). About 75% of patients present

with fever, cough, and dyspnea. The rapid progression

of clinical symptoms is characteristic of staphylococcal

pneumonia.

Chest radiographs in the early stage of

staphylococcal pneumonia may be normal or show a

minimal focal infiltrate. In general, there is a rapid

progression of radiographic findings over just a few

hours. The segmental bronchopneumonia pattern is

usually unilateral and then expands to involve other

lobes. In the case of our patient here, he presented

with abdominal pain and tachypnea. A small infiltrate

was noted which progressed to a large pleural effusion

over a few hours.

About 71% of pneumonias due to Staph aureus

have associated pleural effusions. The effusion is on

the right in 65%, on the left in 15% and bilateral 20% of

the time. This frequently progresses to an empyema.

Ultrasound or CT is often helpful in locating the

loculated fluid.

A pulmonary pneumatocele is a frequent

complication of staphylococcal pneumonia with an

incidence of greater than 85%. There are usually

multiple pneumatoceles which vary in size.

Pneumatoceles are believed to be caused by a partial

airway obstruction by intraluminal exudate or a

peribronchial abscess.

A lung abscess is another complication of

staphylococcal pneumonia. An abscess is a relatively

thick-walled cavity, in contrast to a pneumatocele which

is usually a thin-walled radiolucent area. Fluid levels

may be present in both pneumatoceles and abscesses.

The incidence of pneumothorax associated with

staphylococcal pneumonia is between 40% to 60%. A

pneumothorax may result from a pneumatocele rupture

or formation of a bronchopleural fistula (localized

bronchial wall necrosis). A pyopneumothorax

(pneumothorax + empyema) is highly suggestive of

staphylococcal pneumonia.

Empyemas require drainage with large bore tube

thoracostomies. The empyema is often rapidly

progressive, which leads to compression of the lung

and respiratory failure unless the empyema is drained.

It is likely to reaccumulate following a thoracentesis.

Chest tube thoracostomy also has the benefit of

maintaining lung expansion if a pneumothorax

develops.

A pathogen is recovered from patients with

pneumonia and effusions about 76% of the time. Of

these, pleural fluid cultures are positive in 86% and

blood cultures are positive in 10%.

Although antibiotic coverage with anti-staphylococcal

penicillins (e.g., oxacillin) or first generation

cephalosporins (e.g.. cefazolin) is usually sufficient,

there is a substantial rate of resistance to these drugs.

Methicillin resistant staph aureus will usually be

cephalosporin resistant as well. Vancomycin should be

added to the anti-staphylococcal antibiotic regimen until

sensitivities of the organism are determined.

Complications of staphylococcal pneumonia include

endocarditis, purulent pericarditis, osteomyelitis, deep

tissue abscess, septic arthritis, and meningitis.

References

Chartrand SA, McCracken GH. Staphylococcal

pneumonia in infants and children. Ped Infect Dis

1982;1:19-23.

Forbes GB, Emerson GL. Staphylococcal

pneumonia and empyema. Pediat Clin N Amer

1957;4:215-229.

Melish ME. Staphylococcal Infections. In: Feigin

RD, Cherry JD (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Infectious

Diseases, 2nd edition, 1987, Philadelphia, WB

Saunders Company, pp. 1260-1292.