A Second Look at a Coin in the Stomach

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 2, Case 9

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Alson S. Inaba, MD

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

This is a 20 month old female who presents to the

emergency department after swallowing a coin,

according to two older children who were playing with

her at the time. They don't know what type of coin it

was. Her mother has not noted any difficulty

swallowing, drooling, or respiratory difficulty.

Exam VS T37.1 (tympanic), P100, R36, BP 100/65,

oxygen saturation 99% in room air. Alert, active, no

distress, no drooling. Eyes clear, TM's normal. Oral

clear, moist mucosa. Neck supple. Heart regular

without murmurs. Lungs clear. No stridor, no

wheezing, no coughing, no tachypnea, no retractions.

Abdomen soft, flat, non-tender, bowel sounds active.

Color, perfusion good. Speech normal for age.

Ambulating well.

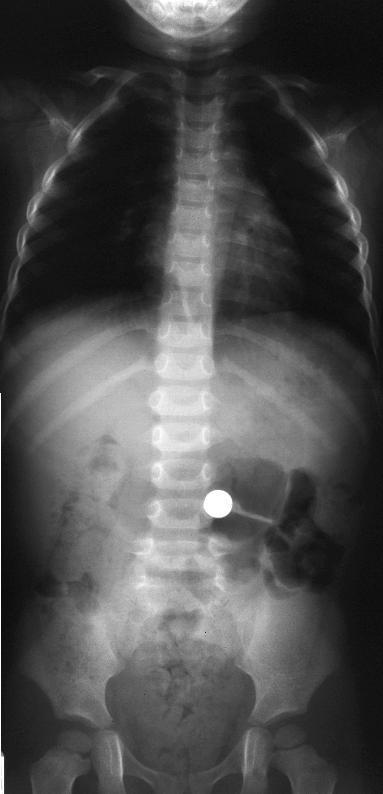

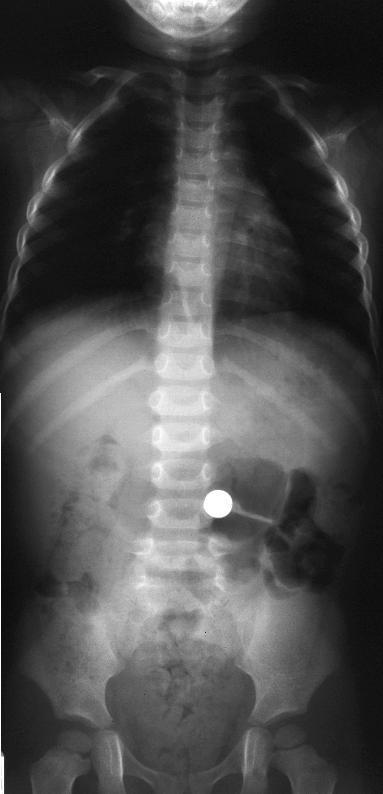

An AP radiograph of her trunk is taken.

View AP film.

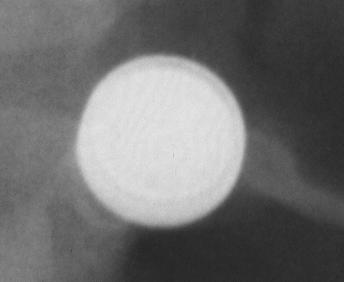

This radiograph shows a coin in her stomach.

However, upon closer inspection, it has an unusual

appearance.

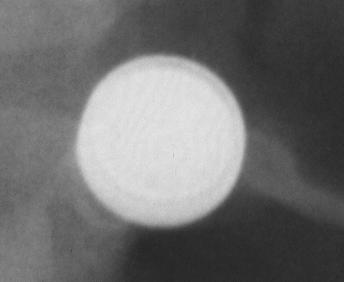

View close-up of coin.

This radiograph shows a coin in her stomach.

However, upon closer inspection, it has an unusual

appearance.

View close-up of coin.

The "coin" shows an internal ring just inside its

perimeter. This internal ring indicates that this is a disc

battery, not a coin. Since disk batteries (also called

button batteries) have different GI consequences

compared to coins, it is important to distinguish an

ingested coin from a disc battery by history or

radiographically. Disc batteries will often have the

characteristic internal ring appearance if taken in the AP

direction. If taken in the lateral position (on edge), it

may show a bulge on one side (bilaminar appearance).

When viewed obliquely, it may be difficult to distinguish

a coin from a disc battery since none of these signs

may be radiographically evident.

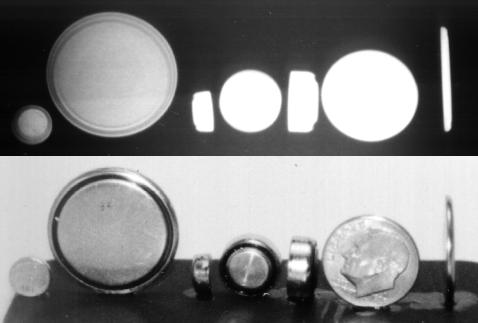

View lineup of disc batteries.

The "coin" shows an internal ring just inside its

perimeter. This internal ring indicates that this is a disc

battery, not a coin. Since disk batteries (also called

button batteries) have different GI consequences

compared to coins, it is important to distinguish an

ingested coin from a disc battery by history or

radiographically. Disc batteries will often have the

characteristic internal ring appearance if taken in the AP

direction. If taken in the lateral position (on edge), it

may show a bulge on one side (bilaminar appearance).

When viewed obliquely, it may be difficult to distinguish

a coin from a disc battery since none of these signs

may be radiographically evident.

View lineup of disc batteries.

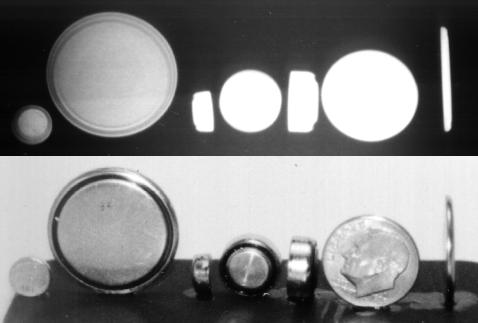

This lineup shows a radiograph of a series of 6 disc

batteries and a dime. The first disc battery on the left

has the positive terminal facing toward us. The second

battery from the left has its negative terminal facing

toward us. On this second battery, the black plastic

insulator is visible in the photograph. However, the

radiograph of both the first and the second disc

batteries show the internal ring sign of the plastic

insulator. The black plastic insulator on the first battery

is on the other side of the battery. The radiograph will

still show the internal ring of the plastic insulator

regardless of which way the battery is facing (AP or

PA). The fourth battery from the left also shows a

plastic insulator, but the radiograph of this battery does

not show the internal ring. It could be absent because

the battery casing is thicker than the first and second

batteries. Thus, the absence of the internal ring

radiographically does not rule out a disc battery since

the appearance of the internal ring is highly dependent

on the degree of X-ray penetration, the angle of the

battery, and the thickness of the battery casing.

The third and fifth batteries from the left are viewed

from the side. On its side view, the battery has a

rectangular appearance with a bulge on one end. This

bulge represents the negative terminal of the battery as

shown in the corresponding photo below it. The

radiographic shadow also identifies this bulge which can

be described as frosting on the cake (bilaminar

appearance). However, this radiographic sign may be

absent if the battery is oriented obliquely, or if the

battery is very thin. The battery to the extreme right is

oriented on edge. The side view of this battery does

not easily show the bulge of the negative terminal

because this battery is very thin as can be seen in the

photograph.

Disc batteries contain various chemicals depending

on the type. Standard dry cell batteries contain

zinc-carbon, alkaline, and nickel-cadmium compounds,

but these are generally not found in disc batteries. Disc

batteries generally contain silver oxide, mercuric oxide,

or lithium salts. They may also contain concentrated

caustics of potassium or sodium hydroxide. Most disc

batteries in use today are the silver oxide or lithium

types. However, many inexpensive or disposable child

toys may still contain the less expensive mercuric oxide

disc batteries.

Disc batteries lodged in the esophagus can

potentially cause serious problems in three ways: 1)

Direct pressure necrosis (similar to coins or other inert

foreign bodies). 2) Caustic injury due to the leakage of

sodium or potassium hydroxide from a leaking battery.

3) The esophagus can also sustain injury from low

voltage burns from a disc battery that still has a charge.

For these reasons, all disc batteries lodged in the

esophagus should be removed expeditiously to avoid

these injuries.

Disc batteries that leak can also cause toxicity from

the absorption of metal compounds. Mercuric oxide

batteries can potentially cause mercury poisoning

resulting in gastritis, vomiting, and hypovolemic shock.

This is not likely to occur for several reasons: 1) Most

disc batteries do not leak. They negotiate the GI tract

and are passed intact in the stool. 2) Most of the

mercuric oxide from old batteries is converted to

insoluble metallic mercury which is not absorbed. 3)

Any mercuric oxide that happens to leak out of the

battery is converted to elemental mercury in the

presence of gastric acids.

Silver salts from silver oxide batteries may be

corrosive, but they are minimally toxic. Lithium is a

highly reactive metal under extreme conditions such as

fire. Complications have not been reported in the

literature following ingestion of a lithium disc battery.

Most disc batteries will pass through the GI tract

without difficulty. A radiograph should be taken to

localize the battery. Esophageal batteries should be

removed expeditiously. If the battery is beyond the

esophagus, the patient may be sent home and

instructed to watch for symptoms of toxicity and

passage of the battery in the stool by straining all

stools. Induction of emesis is generally not successful

and it may be potentially harmful since the battery is

potentially caustic. A repeat radiograph is usually not

indicated until 4 to 7 days after the ingestion if the

battery has not been recovered. Cathartics may

accelerate passage of the battery. If passage is

delayed, the risk of leakage and the potential for

complications depending on the contents of the battery

must be assessed to determine the need for

endoscopic or surgical removal. Although most

batteries will remain intact for two weeks or more, some

batteries may have defective casings or they may be

old and be leaking at the time the battery is swallowed.

References.

Poisindex. Volume 83, Expires 2/28/95. Micromdex

Inc.

Kuhns DW, Dire DJ. Button battery ingestions. Ann

Emerg Med 1989;18:293.

Maves MD, Lloyd TV, Carithers JS. Radiographic

identification of ingested disk batteries. Pediatr Radiol

1986;16:154.

Sheikh A. Button battery ingestions in children.

Pediatr Emerg Care 1993;9:224.

Temple DM, McNeese MC. Hazards of battery

ingestion. Pediatrics 1983;71:100.

This lineup shows a radiograph of a series of 6 disc

batteries and a dime. The first disc battery on the left

has the positive terminal facing toward us. The second

battery from the left has its negative terminal facing

toward us. On this second battery, the black plastic

insulator is visible in the photograph. However, the

radiograph of both the first and the second disc

batteries show the internal ring sign of the plastic

insulator. The black plastic insulator on the first battery

is on the other side of the battery. The radiograph will

still show the internal ring of the plastic insulator

regardless of which way the battery is facing (AP or

PA). The fourth battery from the left also shows a

plastic insulator, but the radiograph of this battery does

not show the internal ring. It could be absent because

the battery casing is thicker than the first and second

batteries. Thus, the absence of the internal ring

radiographically does not rule out a disc battery since

the appearance of the internal ring is highly dependent

on the degree of X-ray penetration, the angle of the

battery, and the thickness of the battery casing.

The third and fifth batteries from the left are viewed

from the side. On its side view, the battery has a

rectangular appearance with a bulge on one end. This

bulge represents the negative terminal of the battery as

shown in the corresponding photo below it. The

radiographic shadow also identifies this bulge which can

be described as frosting on the cake (bilaminar

appearance). However, this radiographic sign may be

absent if the battery is oriented obliquely, or if the

battery is very thin. The battery to the extreme right is

oriented on edge. The side view of this battery does

not easily show the bulge of the negative terminal

because this battery is very thin as can be seen in the

photograph.

Disc batteries contain various chemicals depending

on the type. Standard dry cell batteries contain

zinc-carbon, alkaline, and nickel-cadmium compounds,

but these are generally not found in disc batteries. Disc

batteries generally contain silver oxide, mercuric oxide,

or lithium salts. They may also contain concentrated

caustics of potassium or sodium hydroxide. Most disc

batteries in use today are the silver oxide or lithium

types. However, many inexpensive or disposable child

toys may still contain the less expensive mercuric oxide

disc batteries.

Disc batteries lodged in the esophagus can

potentially cause serious problems in three ways: 1)

Direct pressure necrosis (similar to coins or other inert

foreign bodies). 2) Caustic injury due to the leakage of

sodium or potassium hydroxide from a leaking battery.

3) The esophagus can also sustain injury from low

voltage burns from a disc battery that still has a charge.

For these reasons, all disc batteries lodged in the

esophagus should be removed expeditiously to avoid

these injuries.

Disc batteries that leak can also cause toxicity from

the absorption of metal compounds. Mercuric oxide

batteries can potentially cause mercury poisoning

resulting in gastritis, vomiting, and hypovolemic shock.

This is not likely to occur for several reasons: 1) Most

disc batteries do not leak. They negotiate the GI tract

and are passed intact in the stool. 2) Most of the

mercuric oxide from old batteries is converted to

insoluble metallic mercury which is not absorbed. 3)

Any mercuric oxide that happens to leak out of the

battery is converted to elemental mercury in the

presence of gastric acids.

Silver salts from silver oxide batteries may be

corrosive, but they are minimally toxic. Lithium is a

highly reactive metal under extreme conditions such as

fire. Complications have not been reported in the

literature following ingestion of a lithium disc battery.

Most disc batteries will pass through the GI tract

without difficulty. A radiograph should be taken to

localize the battery. Esophageal batteries should be

removed expeditiously. If the battery is beyond the

esophagus, the patient may be sent home and

instructed to watch for symptoms of toxicity and

passage of the battery in the stool by straining all

stools. Induction of emesis is generally not successful

and it may be potentially harmful since the battery is

potentially caustic. A repeat radiograph is usually not

indicated until 4 to 7 days after the ingestion if the

battery has not been recovered. Cathartics may

accelerate passage of the battery. If passage is

delayed, the risk of leakage and the potential for

complications depending on the contents of the battery

must be assessed to determine the need for

endoscopic or surgical removal. Although most

batteries will remain intact for two weeks or more, some

batteries may have defective casings or they may be

old and be leaking at the time the battery is swallowed.

References.

Poisindex. Volume 83, Expires 2/28/95. Micromdex

Inc.

Kuhns DW, Dire DJ. Button battery ingestions. Ann

Emerg Med 1989;18:293.

Maves MD, Lloyd TV, Carithers JS. Radiographic

identification of ingested disk batteries. Pediatr Radiol

1986;16:154.

Sheikh A. Button battery ingestions in children.

Pediatr Emerg Care 1993;9:224.

Temple DM, McNeese MC. Hazards of battery

ingestion. Pediatrics 1983;71:100.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

This radiograph shows a coin in her stomach.

However, upon closer inspection, it has an unusual

appearance.

View close-up of coin.

This radiograph shows a coin in her stomach.

However, upon closer inspection, it has an unusual

appearance.

View close-up of coin.

The "coin" shows an internal ring just inside its

perimeter. This internal ring indicates that this is a disc

battery, not a coin. Since disk batteries (also called

button batteries) have different GI consequences

compared to coins, it is important to distinguish an

ingested coin from a disc battery by history or

radiographically. Disc batteries will often have the

characteristic internal ring appearance if taken in the AP

direction. If taken in the lateral position (on edge), it

may show a bulge on one side (bilaminar appearance).

When viewed obliquely, it may be difficult to distinguish

a coin from a disc battery since none of these signs

may be radiographically evident.

View lineup of disc batteries.

The "coin" shows an internal ring just inside its

perimeter. This internal ring indicates that this is a disc

battery, not a coin. Since disk batteries (also called

button batteries) have different GI consequences

compared to coins, it is important to distinguish an

ingested coin from a disc battery by history or

radiographically. Disc batteries will often have the

characteristic internal ring appearance if taken in the AP

direction. If taken in the lateral position (on edge), it

may show a bulge on one side (bilaminar appearance).

When viewed obliquely, it may be difficult to distinguish

a coin from a disc battery since none of these signs

may be radiographically evident.

View lineup of disc batteries.

This lineup shows a radiograph of a series of 6 disc

batteries and a dime. The first disc battery on the left

has the positive terminal facing toward us. The second

battery from the left has its negative terminal facing

toward us. On this second battery, the black plastic

insulator is visible in the photograph. However, the

radiograph of both the first and the second disc

batteries show the internal ring sign of the plastic

insulator. The black plastic insulator on the first battery

is on the other side of the battery. The radiograph will

still show the internal ring of the plastic insulator

regardless of which way the battery is facing (AP or

PA). The fourth battery from the left also shows a

plastic insulator, but the radiograph of this battery does

not show the internal ring. It could be absent because

the battery casing is thicker than the first and second

batteries. Thus, the absence of the internal ring

radiographically does not rule out a disc battery since

the appearance of the internal ring is highly dependent

on the degree of X-ray penetration, the angle of the

battery, and the thickness of the battery casing.

The third and fifth batteries from the left are viewed

from the side. On its side view, the battery has a

rectangular appearance with a bulge on one end. This

bulge represents the negative terminal of the battery as

shown in the corresponding photo below it. The

radiographic shadow also identifies this bulge which can

be described as frosting on the cake (bilaminar

appearance). However, this radiographic sign may be

absent if the battery is oriented obliquely, or if the

battery is very thin. The battery to the extreme right is

oriented on edge. The side view of this battery does

not easily show the bulge of the negative terminal

because this battery is very thin as can be seen in the

photograph.

Disc batteries contain various chemicals depending

on the type. Standard dry cell batteries contain

zinc-carbon, alkaline, and nickel-cadmium compounds,

but these are generally not found in disc batteries. Disc

batteries generally contain silver oxide, mercuric oxide,

or lithium salts. They may also contain concentrated

caustics of potassium or sodium hydroxide. Most disc

batteries in use today are the silver oxide or lithium

types. However, many inexpensive or disposable child

toys may still contain the less expensive mercuric oxide

disc batteries.

Disc batteries lodged in the esophagus can

potentially cause serious problems in three ways: 1)

Direct pressure necrosis (similar to coins or other inert

foreign bodies). 2) Caustic injury due to the leakage of

sodium or potassium hydroxide from a leaking battery.

3) The esophagus can also sustain injury from low

voltage burns from a disc battery that still has a charge.

For these reasons, all disc batteries lodged in the

esophagus should be removed expeditiously to avoid

these injuries.

Disc batteries that leak can also cause toxicity from

the absorption of metal compounds. Mercuric oxide

batteries can potentially cause mercury poisoning

resulting in gastritis, vomiting, and hypovolemic shock.

This is not likely to occur for several reasons: 1) Most

disc batteries do not leak. They negotiate the GI tract

and are passed intact in the stool. 2) Most of the

mercuric oxide from old batteries is converted to

insoluble metallic mercury which is not absorbed. 3)

Any mercuric oxide that happens to leak out of the

battery is converted to elemental mercury in the

presence of gastric acids.

Silver salts from silver oxide batteries may be

corrosive, but they are minimally toxic. Lithium is a

highly reactive metal under extreme conditions such as

fire. Complications have not been reported in the

literature following ingestion of a lithium disc battery.

Most disc batteries will pass through the GI tract

without difficulty. A radiograph should be taken to

localize the battery. Esophageal batteries should be

removed expeditiously. If the battery is beyond the

esophagus, the patient may be sent home and

instructed to watch for symptoms of toxicity and

passage of the battery in the stool by straining all

stools. Induction of emesis is generally not successful

and it may be potentially harmful since the battery is

potentially caustic. A repeat radiograph is usually not

indicated until 4 to 7 days after the ingestion if the

battery has not been recovered. Cathartics may

accelerate passage of the battery. If passage is

delayed, the risk of leakage and the potential for

complications depending on the contents of the battery

must be assessed to determine the need for

endoscopic or surgical removal. Although most

batteries will remain intact for two weeks or more, some

batteries may have defective casings or they may be

old and be leaking at the time the battery is swallowed.

References.

Poisindex. Volume 83, Expires 2/28/95. Micromdex

Inc.

Kuhns DW, Dire DJ. Button battery ingestions. Ann

Emerg Med 1989;18:293.

Maves MD, Lloyd TV, Carithers JS. Radiographic

identification of ingested disk batteries. Pediatr Radiol

1986;16:154.

Sheikh A. Button battery ingestions in children.

Pediatr Emerg Care 1993;9:224.

Temple DM, McNeese MC. Hazards of battery

ingestion. Pediatrics 1983;71:100.

This lineup shows a radiograph of a series of 6 disc

batteries and a dime. The first disc battery on the left

has the positive terminal facing toward us. The second

battery from the left has its negative terminal facing

toward us. On this second battery, the black plastic

insulator is visible in the photograph. However, the

radiograph of both the first and the second disc

batteries show the internal ring sign of the plastic

insulator. The black plastic insulator on the first battery

is on the other side of the battery. The radiograph will

still show the internal ring of the plastic insulator

regardless of which way the battery is facing (AP or

PA). The fourth battery from the left also shows a

plastic insulator, but the radiograph of this battery does

not show the internal ring. It could be absent because

the battery casing is thicker than the first and second

batteries. Thus, the absence of the internal ring

radiographically does not rule out a disc battery since

the appearance of the internal ring is highly dependent

on the degree of X-ray penetration, the angle of the

battery, and the thickness of the battery casing.

The third and fifth batteries from the left are viewed

from the side. On its side view, the battery has a

rectangular appearance with a bulge on one end. This

bulge represents the negative terminal of the battery as

shown in the corresponding photo below it. The

radiographic shadow also identifies this bulge which can

be described as frosting on the cake (bilaminar

appearance). However, this radiographic sign may be

absent if the battery is oriented obliquely, or if the

battery is very thin. The battery to the extreme right is

oriented on edge. The side view of this battery does

not easily show the bulge of the negative terminal

because this battery is very thin as can be seen in the

photograph.

Disc batteries contain various chemicals depending

on the type. Standard dry cell batteries contain

zinc-carbon, alkaline, and nickel-cadmium compounds,

but these are generally not found in disc batteries. Disc

batteries generally contain silver oxide, mercuric oxide,

or lithium salts. They may also contain concentrated

caustics of potassium or sodium hydroxide. Most disc

batteries in use today are the silver oxide or lithium

types. However, many inexpensive or disposable child

toys may still contain the less expensive mercuric oxide

disc batteries.

Disc batteries lodged in the esophagus can

potentially cause serious problems in three ways: 1)

Direct pressure necrosis (similar to coins or other inert

foreign bodies). 2) Caustic injury due to the leakage of

sodium or potassium hydroxide from a leaking battery.

3) The esophagus can also sustain injury from low

voltage burns from a disc battery that still has a charge.

For these reasons, all disc batteries lodged in the

esophagus should be removed expeditiously to avoid

these injuries.

Disc batteries that leak can also cause toxicity from

the absorption of metal compounds. Mercuric oxide

batteries can potentially cause mercury poisoning

resulting in gastritis, vomiting, and hypovolemic shock.

This is not likely to occur for several reasons: 1) Most

disc batteries do not leak. They negotiate the GI tract

and are passed intact in the stool. 2) Most of the

mercuric oxide from old batteries is converted to

insoluble metallic mercury which is not absorbed. 3)

Any mercuric oxide that happens to leak out of the

battery is converted to elemental mercury in the

presence of gastric acids.

Silver salts from silver oxide batteries may be

corrosive, but they are minimally toxic. Lithium is a

highly reactive metal under extreme conditions such as

fire. Complications have not been reported in the

literature following ingestion of a lithium disc battery.

Most disc batteries will pass through the GI tract

without difficulty. A radiograph should be taken to

localize the battery. Esophageal batteries should be

removed expeditiously. If the battery is beyond the

esophagus, the patient may be sent home and

instructed to watch for symptoms of toxicity and

passage of the battery in the stool by straining all

stools. Induction of emesis is generally not successful

and it may be potentially harmful since the battery is

potentially caustic. A repeat radiograph is usually not

indicated until 4 to 7 days after the ingestion if the

battery has not been recovered. Cathartics may

accelerate passage of the battery. If passage is

delayed, the risk of leakage and the potential for

complications depending on the contents of the battery

must be assessed to determine the need for

endoscopic or surgical removal. Although most

batteries will remain intact for two weeks or more, some

batteries may have defective casings or they may be

old and be leaking at the time the battery is swallowed.

References.

Poisindex. Volume 83, Expires 2/28/95. Micromdex

Inc.

Kuhns DW, Dire DJ. Button battery ingestions. Ann

Emerg Med 1989;18:293.

Maves MD, Lloyd TV, Carithers JS. Radiographic

identification of ingested disk batteries. Pediatr Radiol

1986;16:154.

Sheikh A. Button battery ingestions in children.

Pediatr Emerg Care 1993;9:224.

Temple DM, McNeese MC. Hazards of battery

ingestion. Pediatrics 1983;71:100.