Moyamoya Disease

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 3, Case 9

Karen R. Sevigny Brown, MD

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

This is a previously healthy, right-handed 7-year old

Asian female who presents to the E.D three hours after

developing right sided weakness of sudden onset. She

had been feeling well until noon, when she developed

weakness of her right hand and was unable to feed

herself. She sat up and tried to walk to her room. Her

father noted that her right leg was "crooked" and she

kept falling to the right. Her arm was "hanging to the

side" and was not swinging properly. Her father also

noted that her smile was "crooked." She has remained

alert through this illness. There is no history of fever,

trauma, seizures, loss of consciousness, headaches,

migraines or palpitations.

Exam: VS T37, P110, R24, BP 105/58. Weight 19

kg (10th percentile), Height 114 cm (10th percentile).

She is healthy appearing, cooperative, and alert in no

distress. She speaks well without dysarthria or

aphasia. Head normocephalic. Optic disc margins

sharp. TM's normal. Oral mucosa clear. Neck supple,

no bruits. Heart regular, grade 1/6 systolic ejection

murmur, vibratory in quality, at the left sternal border.

Lungs clear. Abdomen benign. Color and perfusion

are good.

Cranial nerve findings: Vision is intact. Pupils equal

and reactive. EOM's full. Peripheral fields full. Hearing

intact. Her tongue is midline. Her uvula deviates to the

left. There is an obvious flattening of the right

nasolabial fold and weakness of the right face.

Specifically, weak closure of the right eye and

movement of the forehead on the right. Her facial

sensation is intact. Her masseter function is not weak.

Trapezius function is good bilaterally.

Extremities: Using 4/4 as full strength, her right UE

is 2/4 and her right LE is 2/4. Her left side is not weak.

DTR's are 3+ bilaterally. There is a positive Babinski

sign on the right. Her left plantar reflex is downgoing.

Sensation is fully intact. Her observed gait is obviously

unsteady. She falls to the right. Her cerebellar function

is hard to test on her right because of her weakness.

Her left side is normal.

A CT scan is obtained. Before we see the result of

the CT scan, can you estimate where her CNS "lesion"

is likely to be.

1) Brain versus spinal cord ?

2) Are her findings due to a small lesion or a large

infarct as seen in the typical ACA (anterior cerebral

artery) and MCA (middle cerebral artery) distributions?

3) Is this likely to be a neoplasm, a hemorrhage, or

an infarct?

This is not a spinal cord lesion since she has

extensive facial involvement.

A large infarct is not likely since she is alert.

Additionally, her motor findings extend from her face to

her lower extremities without affecting speech and

language. This is most likely a smaller lesion.

The sudden onset makes a neoplasm less likely

although neoplasms can hemorrhage and undergo

sudden expansion. A hemorrhage is less likely since

her symptoms are not progressing, she has no

headache, and has no signs of increased intracranial

pressure. An infarct is uncommon in this age group,

however, a small infarct would account for her findings

and the sudden onset.

4) Where is her lesion likely to be?

It is most likely to be in a small area where the motor

fibers (both corticospinal and corticobulbar), originating

from the left brain, come together. Since her sensation

is unaffected, sensory pathways should be unaffected.

A likely possibility is the posterior limb of internal

capsule.

For a brief of review of the neuroanatomy of the

brain in this region, refer to the diagram at any time.

View neuroanatomy.

L = Lateral ventricles. The anterior horns and the

posterior horns are shown in this diagram.

3 = Third ventricle.

CC = Corpus callosum.

C = Caudate nucleus.

P = Putamen

G = Globus Pallidus. The putamen and globus

pallidus together form the lenticular (lentiform) nucleus.

T = Thalamus

Arrows = Internal Capsule [anterior limb, posterior

limb, genu (bend)].

O = Optic radiations.

A = Auditory radiations.

The corticospinal tract originates from the motor

strip of the cerebral cortex. The fibers collect as they

traverse through the posterior limb of internal capsule.

The tract largely crosses the midline in the decussation

of the pyramids. Fibers exit the spinal cord at their

respective levels.

View our patient's CT scan.

L = Lateral ventricles. The anterior horns and the

posterior horns are shown in this diagram.

3 = Third ventricle.

CC = Corpus callosum.

C = Caudate nucleus.

P = Putamen

G = Globus Pallidus. The putamen and globus

pallidus together form the lenticular (lentiform) nucleus.

T = Thalamus

Arrows = Internal Capsule [anterior limb, posterior

limb, genu (bend)].

O = Optic radiations.

A = Auditory radiations.

The corticospinal tract originates from the motor

strip of the cerebral cortex. The fibers collect as they

traverse through the posterior limb of internal capsule.

The tract largely crosses the midline in the decussation

of the pyramids. Fibers exit the spinal cord at their

respective levels.

View our patient's CT scan.

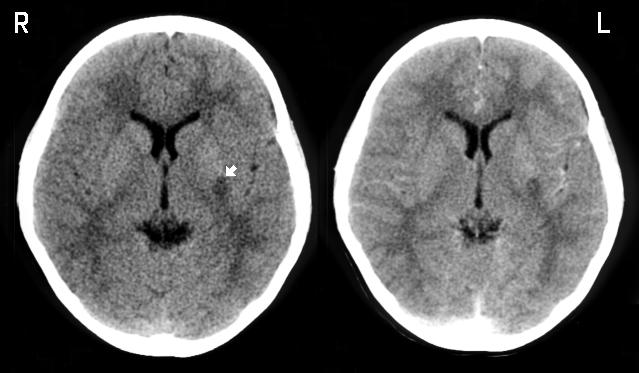

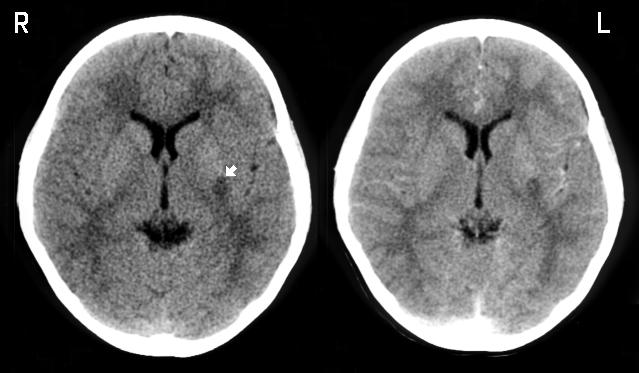

The image on the left is without contrast. The same

cut is shown on the right with contrast. The patient's

right is to the left of the image as marked. There is a

hypodense region in the left posterior basal ganglia.

The white arrow points to this region which is in the

area of the putamen adjacent to the posterior limb of

internal capsule. Although the neuroanatomy on the CT

scan is not well defined, you should still be able to

identify the caudate nucleus, the lenticular nucleus, and

the thalamus. The internal capsule can be identified

faintly. The posterior limb is located between the

thalamus and the lenticular nucleus. The anterior limb

is located between the caudate nucleus and the

lenticular nucleus. There is no significant mass

effect. This hypodensity does not enhance with

contrast suggesting that this is an ischemic lesion.

A pediatric neurologist is consulted and she is

admitted to the hospital. An MRI scan is obtained.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is also

performed.

View MRI scan.

The image on the left is without contrast. The same

cut is shown on the right with contrast. The patient's

right is to the left of the image as marked. There is a

hypodense region in the left posterior basal ganglia.

The white arrow points to this region which is in the

area of the putamen adjacent to the posterior limb of

internal capsule. Although the neuroanatomy on the CT

scan is not well defined, you should still be able to

identify the caudate nucleus, the lenticular nucleus, and

the thalamus. The internal capsule can be identified

faintly. The posterior limb is located between the

thalamus and the lenticular nucleus. The anterior limb

is located between the caudate nucleus and the

lenticular nucleus. There is no significant mass

effect. This hypodensity does not enhance with

contrast suggesting that this is an ischemic lesion.

A pediatric neurologist is consulted and she is

admitted to the hospital. An MRI scan is obtained.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is also

performed.

View MRI scan.

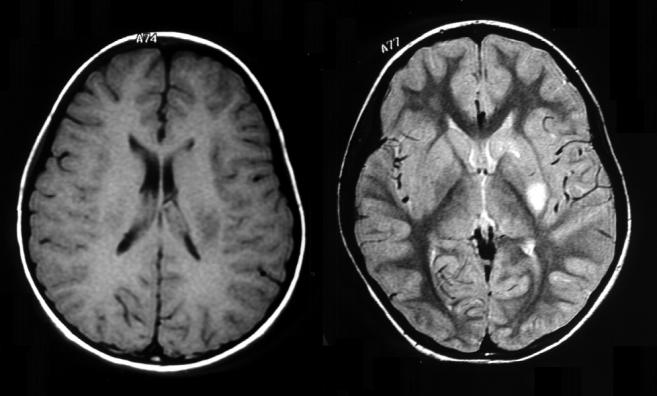

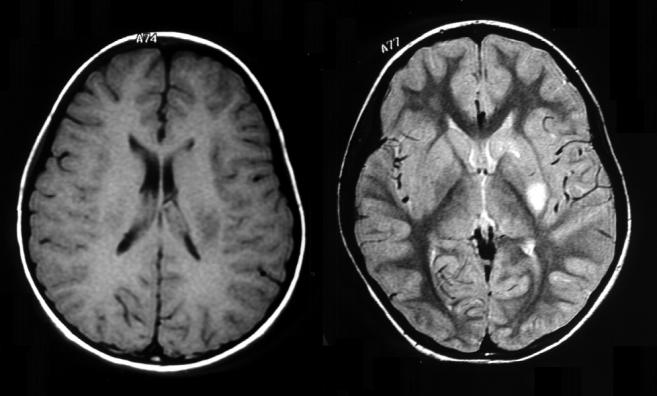

T1 (left image) and T2 (right image) weighted axial

images are shown (different levels). On the T1 image,

the ventricles appear to be dark and the infarct seen in

the left lenticular nucleus is dark as well. The T2 image

is a lower cut through the center of the infarct. The T2

image shows the CSF within the ventricles to be white.

The infarct appears as a white lesion in the caudate

nucleus and the left putamen. In the T2 image, internal

capsule is dark. Note the obvious distortion of the

anterior limb of the left internal capsule, compared to

the right. The posterior limb of the left internal capsule

is also slightly distorted (compared to the right) adjacent

to the infarct in the putamen. This study is read as an

infarct in the left basal ganglia, the posterior limb of

internal capsule, and the head of the caudate.

The structures of this T2 image are labeled if you

have difficulty identifying the structures.

T1 (left image) and T2 (right image) weighted axial

images are shown (different levels). On the T1 image,

the ventricles appear to be dark and the infarct seen in

the left lenticular nucleus is dark as well. The T2 image

is a lower cut through the center of the infarct. The T2

image shows the CSF within the ventricles to be white.

The infarct appears as a white lesion in the caudate

nucleus and the left putamen. In the T2 image, internal

capsule is dark. Note the obvious distortion of the

anterior limb of the left internal capsule, compared to

the right. The posterior limb of the left internal capsule

is also slightly distorted (compared to the right) adjacent

to the infarct in the putamen. This study is read as an

infarct in the left basal ganglia, the posterior limb of

internal capsule, and the head of the caudate.

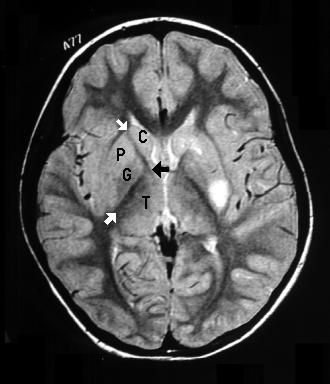

The structures of this T2 image are labeled if you

have difficulty identifying the structures.

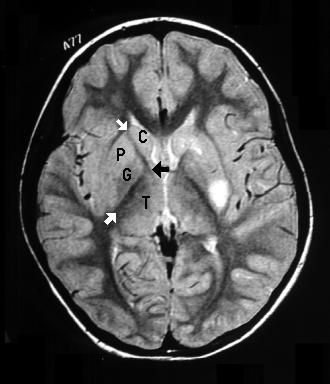

The white arrows point to the anterior and posterior limb

of internal capsule. The black arrow points to the genu.

The other labeled structures are the caudate nucleus

(C), globus pallidus (G), putamen (P), and thalamus

(T). The lateral ventricles are white.

View MRA study.

The white arrows point to the anterior and posterior limb

of internal capsule. The black arrow points to the genu.

The other labeled structures are the caudate nucleus

(C), globus pallidus (G), putamen (P), and thalamus

(T). The lateral ventricles are white.

View MRA study.

There is obvious narrowing and irregularity of the left

internal carotid artery and its branches. The arrow on

the right points to the supraclinoid portion of the internal

carotid. The arrow on the left points to the horizonal

section of the anterior cerebral artery. She is

tentatively diagnosed with Moyamoya syndrome. An

angiogram is ordered.

View angiogram.

There is obvious narrowing and irregularity of the left

internal carotid artery and its branches. The arrow on

the right points to the supraclinoid portion of the internal

carotid. The arrow on the left points to the horizonal

section of the anterior cerebral artery. She is

tentatively diagnosed with Moyamoya syndrome. An

angiogram is ordered.

View angiogram.

The image displayed here is an AP view of her left

internal carotid angiogram. The arrows point to

narrowed regions in the internal carotid artery and its

branches. The classic "puff of smoke" pattern seen in

Moyamoya disease was not visualized. This patient

turns out to have probable fibromuscular displasia (a

rare cerebrovascular disease).

View "puff of smoke".

The image displayed here is an AP view of her left

internal carotid angiogram. The arrows point to

narrowed regions in the internal carotid artery and its

branches. The classic "puff of smoke" pattern seen in

Moyamoya disease was not visualized. This patient

turns out to have probable fibromuscular displasia (a

rare cerebrovascular disease).

View "puff of smoke".

The image displayed here is an internal carotid

angiogram taken from a different patient with a more

typical Moyamoya disease angiogram. The black arrow

points to the "puff of smoke" which represents

neovascularization providing collateral blood flow.

There is stenosis of the internal carotid artery proximal

to this puff of smoke. The white arrow points to a

dilated ophthalmic artery which is providing collateral

circulation as well.

Moyamoya disease is a disease of the large cerebral

vessels that results in a network of small collateral

vessels that form a pattern on angiography resembling

a "puff" or "hazy cloud" of smoke (the English

translation of the Japanese term, moyamoya).

Diseased vessels may narrow and occlude resulting in

transient ischemic attacks and/or cerebral infarcts, or

they may rupture resulting in spontaneous intracranial

hemorrhage. Patients may also present with

headaches. This condition presents largely in childhood

and is uncommon (Despite this, three likely cases have

been diagnosed in our center this year). Moyamoya is

often divided into a syndrome and a disease, however,

both are not specific. Not much is known about its

etiology. Its course typically results in progressive

neurological deterioration. While steroids and

vasodilators have little or no effect in the long term

outcome, a surgical procedure shunting intracerebral

vessels may have long term benefit. This patient's

angiographic studies are not diagnostic of Moyamoya.

This may be an early case of Moyamoya or some other

type of vasculopathy.

Strokes in Children

Stroke can be defined as an acute onset neurologic

deficit lasting more than one hour. The

pathophysiologic mechanisms for vascular dysfunction

include cerebral embolism, arterial and/or venous

thrombosis, and intraparenchymal/subarachnoid

hemorrhage. In contrast to adults, cerebral vascular

disease is not usually associated with atherosclerosis,

hypertension, or diabetes.

Sudden loss of function is usually characteristic for a

cerebral embolism. Incomplete improvement may be

seen as the embolus fragments and reperfusion occurs.

Cerebral embolism in children is most often associated

with cardiac disease.

Thrombotic infarction may be difficult to distinguish

from embolic infarction. Cerebral artery thrombosis

takes longer to develop than embolism and may be

preceded by transient ischemic attacks. In children,

arterial thrombosis is related to vasculopathy of cerebral

blood vessels, hemoglobinopathy, and vasculitis.

Venous thrombosis often presents with seizures and

increased intracranial pressure with the most common

causes including infection, dehydration,

hemoglobinopathy, and malignancy.

The presenting signs and symptoms of

intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhage

include severe headache, vomiting, and deterioration of

function. However, the findings may be very subtle,

such as alteration in mental status and a bulging

fontanelle in infants. Trauma, hematologic disorders

(sickle cell disease), vascular malformations (aneurysm

and arteriovenous malformations) and inflammatory

disease are among the most common causes of

strokes in children. Child abuse should be suspected in

any child with an unexplained intracranial hemorrhage.

When considering stroke in children, a diverse

differential diagnosis must be considered. Hemiplegia

with other focal deficits can follow a seizure (Todd's

paralysis). Usually this dysfunction resolves within 6

hours with complete resolution by 24 hours. A child

may frequently be found hemiplegic in the morning

following an unwitnessed nocturnal seizure. An

intracranial mass, either neoplasm or abscess, may

mimic a vascular lesion. Tumors may often

hemorrhage into a necrotic area, with localized

compression or invasion of intracranial vascular

structures. Infection must be considered since multiple

micro-infarcts are a common complication of bacterial

meningitis. Complicated and basilar migraines may be

accompanied by neurologic symptoms, with alternating

hemiplegia attributed to basilar migraine in children.

Several conditions cause stroke in children. Heart

disease is the most common of these, responsible for

one-third of all ischemic infarctions in children. Right to

left (cyanotic) intracardiac shunts can cause

polycythemia, leading to thrombosis and embolism.

Congenital heart disease with valvular defects and/or

cardiomyopathies can lead to thrombus formation and

stroke. Another common cause is hematologic

disorders such as sickle cell disease which is

associated with multiple infarcts. Coagulation disorders

such as hemophilia and platelet disorders have an

increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage and stroke.

Homocystinuria, an uncommon autosomal recessive

disorder, leads to an increased tendency for thrombosis

as a result of endothelial damage from excessive

homocystine, thus leading to platelet aggregation and

thrombus formation. Inherited disorders of the blood

vessel wall can result in hemorrhage (AVM's,

aneurysms, tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis,

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, fibromuscular

dysplasia, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and Fabry

disease).

References

Riela AR, Roach ES. Etiology of Stoke in Children.

Journal of Child Neurology 1993;8:201-220.

Pavlakis SG, Gould RJ, Zito JL. Stroke in Children.

Advances in Pediatrics 1991:151-179.

Matsushima Y, Aoyagi M, Niimi Y, Masaoka H,

Ohno K. Symptoms and Their Pattern of Progression

in Childhood Moyamoya Disease. Brain &

Development 1990;12:784.

Rooney CM, Kaye EM, Scott M, Klucznik RP,

Rosman NP. Modified Encephaloduro-

arteriosynangiosis as a Surgical Treatment of

Childhood Moyamoya Disease: Report of Five Cases.

Journal of Child Neurology 1991;6:24-31.

The image displayed here is an internal carotid

angiogram taken from a different patient with a more

typical Moyamoya disease angiogram. The black arrow

points to the "puff of smoke" which represents

neovascularization providing collateral blood flow.

There is stenosis of the internal carotid artery proximal

to this puff of smoke. The white arrow points to a

dilated ophthalmic artery which is providing collateral

circulation as well.

Moyamoya disease is a disease of the large cerebral

vessels that results in a network of small collateral

vessels that form a pattern on angiography resembling

a "puff" or "hazy cloud" of smoke (the English

translation of the Japanese term, moyamoya).

Diseased vessels may narrow and occlude resulting in

transient ischemic attacks and/or cerebral infarcts, or

they may rupture resulting in spontaneous intracranial

hemorrhage. Patients may also present with

headaches. This condition presents largely in childhood

and is uncommon (Despite this, three likely cases have

been diagnosed in our center this year). Moyamoya is

often divided into a syndrome and a disease, however,

both are not specific. Not much is known about its

etiology. Its course typically results in progressive

neurological deterioration. While steroids and

vasodilators have little or no effect in the long term

outcome, a surgical procedure shunting intracerebral

vessels may have long term benefit. This patient's

angiographic studies are not diagnostic of Moyamoya.

This may be an early case of Moyamoya or some other

type of vasculopathy.

Strokes in Children

Stroke can be defined as an acute onset neurologic

deficit lasting more than one hour. The

pathophysiologic mechanisms for vascular dysfunction

include cerebral embolism, arterial and/or venous

thrombosis, and intraparenchymal/subarachnoid

hemorrhage. In contrast to adults, cerebral vascular

disease is not usually associated with atherosclerosis,

hypertension, or diabetes.

Sudden loss of function is usually characteristic for a

cerebral embolism. Incomplete improvement may be

seen as the embolus fragments and reperfusion occurs.

Cerebral embolism in children is most often associated

with cardiac disease.

Thrombotic infarction may be difficult to distinguish

from embolic infarction. Cerebral artery thrombosis

takes longer to develop than embolism and may be

preceded by transient ischemic attacks. In children,

arterial thrombosis is related to vasculopathy of cerebral

blood vessels, hemoglobinopathy, and vasculitis.

Venous thrombosis often presents with seizures and

increased intracranial pressure with the most common

causes including infection, dehydration,

hemoglobinopathy, and malignancy.

The presenting signs and symptoms of

intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhage

include severe headache, vomiting, and deterioration of

function. However, the findings may be very subtle,

such as alteration in mental status and a bulging

fontanelle in infants. Trauma, hematologic disorders

(sickle cell disease), vascular malformations (aneurysm

and arteriovenous malformations) and inflammatory

disease are among the most common causes of

strokes in children. Child abuse should be suspected in

any child with an unexplained intracranial hemorrhage.

When considering stroke in children, a diverse

differential diagnosis must be considered. Hemiplegia

with other focal deficits can follow a seizure (Todd's

paralysis). Usually this dysfunction resolves within 6

hours with complete resolution by 24 hours. A child

may frequently be found hemiplegic in the morning

following an unwitnessed nocturnal seizure. An

intracranial mass, either neoplasm or abscess, may

mimic a vascular lesion. Tumors may often

hemorrhage into a necrotic area, with localized

compression or invasion of intracranial vascular

structures. Infection must be considered since multiple

micro-infarcts are a common complication of bacterial

meningitis. Complicated and basilar migraines may be

accompanied by neurologic symptoms, with alternating

hemiplegia attributed to basilar migraine in children.

Several conditions cause stroke in children. Heart

disease is the most common of these, responsible for

one-third of all ischemic infarctions in children. Right to

left (cyanotic) intracardiac shunts can cause

polycythemia, leading to thrombosis and embolism.

Congenital heart disease with valvular defects and/or

cardiomyopathies can lead to thrombus formation and

stroke. Another common cause is hematologic

disorders such as sickle cell disease which is

associated with multiple infarcts. Coagulation disorders

such as hemophilia and platelet disorders have an

increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage and stroke.

Homocystinuria, an uncommon autosomal recessive

disorder, leads to an increased tendency for thrombosis

as a result of endothelial damage from excessive

homocystine, thus leading to platelet aggregation and

thrombus formation. Inherited disorders of the blood

vessel wall can result in hemorrhage (AVM's,

aneurysms, tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis,

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, fibromuscular

dysplasia, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and Fabry

disease).

References

Riela AR, Roach ES. Etiology of Stoke in Children.

Journal of Child Neurology 1993;8:201-220.

Pavlakis SG, Gould RJ, Zito JL. Stroke in Children.

Advances in Pediatrics 1991:151-179.

Matsushima Y, Aoyagi M, Niimi Y, Masaoka H,

Ohno K. Symptoms and Their Pattern of Progression

in Childhood Moyamoya Disease. Brain &

Development 1990;12:784.

Rooney CM, Kaye EM, Scott M, Klucznik RP,

Rosman NP. Modified Encephaloduro-

arteriosynangiosis as a Surgical Treatment of

Childhood Moyamoya Disease: Report of Five Cases.

Journal of Child Neurology 1991;6:24-31.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

L = Lateral ventricles. The anterior horns and the

posterior horns are shown in this diagram.

3 = Third ventricle.

CC = Corpus callosum.

C = Caudate nucleus.

P = Putamen

G = Globus Pallidus. The putamen and globus

pallidus together form the lenticular (lentiform) nucleus.

T = Thalamus

Arrows = Internal Capsule [anterior limb, posterior

limb, genu (bend)].

O = Optic radiations.

A = Auditory radiations.

The corticospinal tract originates from the motor

strip of the cerebral cortex. The fibers collect as they

traverse through the posterior limb of internal capsule.

The tract largely crosses the midline in the decussation

of the pyramids. Fibers exit the spinal cord at their

respective levels.

View our patient's CT scan.

L = Lateral ventricles. The anterior horns and the

posterior horns are shown in this diagram.

3 = Third ventricle.

CC = Corpus callosum.

C = Caudate nucleus.

P = Putamen

G = Globus Pallidus. The putamen and globus

pallidus together form the lenticular (lentiform) nucleus.

T = Thalamus

Arrows = Internal Capsule [anterior limb, posterior

limb, genu (bend)].

O = Optic radiations.

A = Auditory radiations.

The corticospinal tract originates from the motor

strip of the cerebral cortex. The fibers collect as they

traverse through the posterior limb of internal capsule.

The tract largely crosses the midline in the decussation

of the pyramids. Fibers exit the spinal cord at their

respective levels.

View our patient's CT scan.

The image on the left is without contrast. The same

cut is shown on the right with contrast. The patient's

right is to the left of the image as marked. There is a

hypodense region in the left posterior basal ganglia.

The white arrow points to this region which is in the

area of the putamen adjacent to the posterior limb of

internal capsule. Although the neuroanatomy on the CT

scan is not well defined, you should still be able to

identify the caudate nucleus, the lenticular nucleus, and

the thalamus. The internal capsule can be identified

faintly. The posterior limb is located between the

thalamus and the lenticular nucleus. The anterior limb

is located between the caudate nucleus and the

lenticular nucleus. There is no significant mass

effect. This hypodensity does not enhance with

contrast suggesting that this is an ischemic lesion.

A pediatric neurologist is consulted and she is

admitted to the hospital. An MRI scan is obtained.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is also

performed.

View MRI scan.

The image on the left is without contrast. The same

cut is shown on the right with contrast. The patient's

right is to the left of the image as marked. There is a

hypodense region in the left posterior basal ganglia.

The white arrow points to this region which is in the

area of the putamen adjacent to the posterior limb of

internal capsule. Although the neuroanatomy on the CT

scan is not well defined, you should still be able to

identify the caudate nucleus, the lenticular nucleus, and

the thalamus. The internal capsule can be identified

faintly. The posterior limb is located between the

thalamus and the lenticular nucleus. The anterior limb

is located between the caudate nucleus and the

lenticular nucleus. There is no significant mass

effect. This hypodensity does not enhance with

contrast suggesting that this is an ischemic lesion.

A pediatric neurologist is consulted and she is

admitted to the hospital. An MRI scan is obtained.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is also

performed.

View MRI scan.

T1 (left image) and T2 (right image) weighted axial

images are shown (different levels). On the T1 image,

the ventricles appear to be dark and the infarct seen in

the left lenticular nucleus is dark as well. The T2 image

is a lower cut through the center of the infarct. The T2

image shows the CSF within the ventricles to be white.

The infarct appears as a white lesion in the caudate

nucleus and the left putamen. In the T2 image, internal

capsule is dark. Note the obvious distortion of the

anterior limb of the left internal capsule, compared to

the right. The posterior limb of the left internal capsule

is also slightly distorted (compared to the right) adjacent

to the infarct in the putamen. This study is read as an

infarct in the left basal ganglia, the posterior limb of

internal capsule, and the head of the caudate.

The structures of this T2 image are labeled if you

have difficulty identifying the structures.

T1 (left image) and T2 (right image) weighted axial

images are shown (different levels). On the T1 image,

the ventricles appear to be dark and the infarct seen in

the left lenticular nucleus is dark as well. The T2 image

is a lower cut through the center of the infarct. The T2

image shows the CSF within the ventricles to be white.

The infarct appears as a white lesion in the caudate

nucleus and the left putamen. In the T2 image, internal

capsule is dark. Note the obvious distortion of the

anterior limb of the left internal capsule, compared to

the right. The posterior limb of the left internal capsule

is also slightly distorted (compared to the right) adjacent

to the infarct in the putamen. This study is read as an

infarct in the left basal ganglia, the posterior limb of

internal capsule, and the head of the caudate.

The structures of this T2 image are labeled if you

have difficulty identifying the structures.

The white arrows point to the anterior and posterior limb

of internal capsule. The black arrow points to the genu.

The other labeled structures are the caudate nucleus

(C), globus pallidus (G), putamen (P), and thalamus

(T). The lateral ventricles are white.

View MRA study.

The white arrows point to the anterior and posterior limb

of internal capsule. The black arrow points to the genu.

The other labeled structures are the caudate nucleus

(C), globus pallidus (G), putamen (P), and thalamus

(T). The lateral ventricles are white.

View MRA study.

There is obvious narrowing and irregularity of the left

internal carotid artery and its branches. The arrow on

the right points to the supraclinoid portion of the internal

carotid. The arrow on the left points to the horizonal

section of the anterior cerebral artery. She is

tentatively diagnosed with Moyamoya syndrome. An

angiogram is ordered.

View angiogram.

There is obvious narrowing and irregularity of the left

internal carotid artery and its branches. The arrow on

the right points to the supraclinoid portion of the internal

carotid. The arrow on the left points to the horizonal

section of the anterior cerebral artery. She is

tentatively diagnosed with Moyamoya syndrome. An

angiogram is ordered.

View angiogram.

The image displayed here is an AP view of her left

internal carotid angiogram. The arrows point to

narrowed regions in the internal carotid artery and its

branches. The classic "puff of smoke" pattern seen in

Moyamoya disease was not visualized. This patient

turns out to have probable fibromuscular displasia (a

rare cerebrovascular disease).

View "puff of smoke".

The image displayed here is an AP view of her left

internal carotid angiogram. The arrows point to

narrowed regions in the internal carotid artery and its

branches. The classic "puff of smoke" pattern seen in

Moyamoya disease was not visualized. This patient

turns out to have probable fibromuscular displasia (a

rare cerebrovascular disease).

View "puff of smoke".

The image displayed here is an internal carotid

angiogram taken from a different patient with a more

typical Moyamoya disease angiogram. The black arrow

points to the "puff of smoke" which represents

neovascularization providing collateral blood flow.

There is stenosis of the internal carotid artery proximal

to this puff of smoke. The white arrow points to a

dilated ophthalmic artery which is providing collateral

circulation as well.

Moyamoya disease is a disease of the large cerebral

vessels that results in a network of small collateral

vessels that form a pattern on angiography resembling

a "puff" or "hazy cloud" of smoke (the English

translation of the Japanese term, moyamoya).

Diseased vessels may narrow and occlude resulting in

transient ischemic attacks and/or cerebral infarcts, or

they may rupture resulting in spontaneous intracranial

hemorrhage. Patients may also present with

headaches. This condition presents largely in childhood

and is uncommon (Despite this, three likely cases have

been diagnosed in our center this year). Moyamoya is

often divided into a syndrome and a disease, however,

both are not specific. Not much is known about its

etiology. Its course typically results in progressive

neurological deterioration. While steroids and

vasodilators have little or no effect in the long term

outcome, a surgical procedure shunting intracerebral

vessels may have long term benefit. This patient's

angiographic studies are not diagnostic of Moyamoya.

This may be an early case of Moyamoya or some other

type of vasculopathy.

Strokes in Children

Stroke can be defined as an acute onset neurologic

deficit lasting more than one hour. The

pathophysiologic mechanisms for vascular dysfunction

include cerebral embolism, arterial and/or venous

thrombosis, and intraparenchymal/subarachnoid

hemorrhage. In contrast to adults, cerebral vascular

disease is not usually associated with atherosclerosis,

hypertension, or diabetes.

Sudden loss of function is usually characteristic for a

cerebral embolism. Incomplete improvement may be

seen as the embolus fragments and reperfusion occurs.

Cerebral embolism in children is most often associated

with cardiac disease.

Thrombotic infarction may be difficult to distinguish

from embolic infarction. Cerebral artery thrombosis

takes longer to develop than embolism and may be

preceded by transient ischemic attacks. In children,

arterial thrombosis is related to vasculopathy of cerebral

blood vessels, hemoglobinopathy, and vasculitis.

Venous thrombosis often presents with seizures and

increased intracranial pressure with the most common

causes including infection, dehydration,

hemoglobinopathy, and malignancy.

The presenting signs and symptoms of

intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhage

include severe headache, vomiting, and deterioration of

function. However, the findings may be very subtle,

such as alteration in mental status and a bulging

fontanelle in infants. Trauma, hematologic disorders

(sickle cell disease), vascular malformations (aneurysm

and arteriovenous malformations) and inflammatory

disease are among the most common causes of

strokes in children. Child abuse should be suspected in

any child with an unexplained intracranial hemorrhage.

When considering stroke in children, a diverse

differential diagnosis must be considered. Hemiplegia

with other focal deficits can follow a seizure (Todd's

paralysis). Usually this dysfunction resolves within 6

hours with complete resolution by 24 hours. A child

may frequently be found hemiplegic in the morning

following an unwitnessed nocturnal seizure. An

intracranial mass, either neoplasm or abscess, may

mimic a vascular lesion. Tumors may often

hemorrhage into a necrotic area, with localized

compression or invasion of intracranial vascular

structures. Infection must be considered since multiple

micro-infarcts are a common complication of bacterial

meningitis. Complicated and basilar migraines may be

accompanied by neurologic symptoms, with alternating

hemiplegia attributed to basilar migraine in children.

Several conditions cause stroke in children. Heart

disease is the most common of these, responsible for

one-third of all ischemic infarctions in children. Right to

left (cyanotic) intracardiac shunts can cause

polycythemia, leading to thrombosis and embolism.

Congenital heart disease with valvular defects and/or

cardiomyopathies can lead to thrombus formation and

stroke. Another common cause is hematologic

disorders such as sickle cell disease which is

associated with multiple infarcts. Coagulation disorders

such as hemophilia and platelet disorders have an

increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage and stroke.

Homocystinuria, an uncommon autosomal recessive

disorder, leads to an increased tendency for thrombosis

as a result of endothelial damage from excessive

homocystine, thus leading to platelet aggregation and

thrombus formation. Inherited disorders of the blood

vessel wall can result in hemorrhage (AVM's,

aneurysms, tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis,

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, fibromuscular

dysplasia, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and Fabry

disease).

References

Riela AR, Roach ES. Etiology of Stoke in Children.

Journal of Child Neurology 1993;8:201-220.

Pavlakis SG, Gould RJ, Zito JL. Stroke in Children.

Advances in Pediatrics 1991:151-179.

Matsushima Y, Aoyagi M, Niimi Y, Masaoka H,

Ohno K. Symptoms and Their Pattern of Progression

in Childhood Moyamoya Disease. Brain &

Development 1990;12:784.

Rooney CM, Kaye EM, Scott M, Klucznik RP,

Rosman NP. Modified Encephaloduro-

arteriosynangiosis as a Surgical Treatment of

Childhood Moyamoya Disease: Report of Five Cases.

Journal of Child Neurology 1991;6:24-31.

The image displayed here is an internal carotid

angiogram taken from a different patient with a more

typical Moyamoya disease angiogram. The black arrow

points to the "puff of smoke" which represents

neovascularization providing collateral blood flow.

There is stenosis of the internal carotid artery proximal

to this puff of smoke. The white arrow points to a

dilated ophthalmic artery which is providing collateral

circulation as well.

Moyamoya disease is a disease of the large cerebral

vessels that results in a network of small collateral

vessels that form a pattern on angiography resembling

a "puff" or "hazy cloud" of smoke (the English

translation of the Japanese term, moyamoya).

Diseased vessels may narrow and occlude resulting in

transient ischemic attacks and/or cerebral infarcts, or

they may rupture resulting in spontaneous intracranial

hemorrhage. Patients may also present with

headaches. This condition presents largely in childhood

and is uncommon (Despite this, three likely cases have

been diagnosed in our center this year). Moyamoya is

often divided into a syndrome and a disease, however,

both are not specific. Not much is known about its

etiology. Its course typically results in progressive

neurological deterioration. While steroids and

vasodilators have little or no effect in the long term

outcome, a surgical procedure shunting intracerebral

vessels may have long term benefit. This patient's

angiographic studies are not diagnostic of Moyamoya.

This may be an early case of Moyamoya or some other

type of vasculopathy.

Strokes in Children

Stroke can be defined as an acute onset neurologic

deficit lasting more than one hour. The

pathophysiologic mechanisms for vascular dysfunction

include cerebral embolism, arterial and/or venous

thrombosis, and intraparenchymal/subarachnoid

hemorrhage. In contrast to adults, cerebral vascular

disease is not usually associated with atherosclerosis,

hypertension, or diabetes.

Sudden loss of function is usually characteristic for a

cerebral embolism. Incomplete improvement may be

seen as the embolus fragments and reperfusion occurs.

Cerebral embolism in children is most often associated

with cardiac disease.

Thrombotic infarction may be difficult to distinguish

from embolic infarction. Cerebral artery thrombosis

takes longer to develop than embolism and may be

preceded by transient ischemic attacks. In children,

arterial thrombosis is related to vasculopathy of cerebral

blood vessels, hemoglobinopathy, and vasculitis.

Venous thrombosis often presents with seizures and

increased intracranial pressure with the most common

causes including infection, dehydration,

hemoglobinopathy, and malignancy.

The presenting signs and symptoms of

intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhage

include severe headache, vomiting, and deterioration of

function. However, the findings may be very subtle,

such as alteration in mental status and a bulging

fontanelle in infants. Trauma, hematologic disorders

(sickle cell disease), vascular malformations (aneurysm

and arteriovenous malformations) and inflammatory

disease are among the most common causes of

strokes in children. Child abuse should be suspected in

any child with an unexplained intracranial hemorrhage.

When considering stroke in children, a diverse

differential diagnosis must be considered. Hemiplegia

with other focal deficits can follow a seizure (Todd's

paralysis). Usually this dysfunction resolves within 6

hours with complete resolution by 24 hours. A child

may frequently be found hemiplegic in the morning

following an unwitnessed nocturnal seizure. An

intracranial mass, either neoplasm or abscess, may

mimic a vascular lesion. Tumors may often

hemorrhage into a necrotic area, with localized

compression or invasion of intracranial vascular

structures. Infection must be considered since multiple

micro-infarcts are a common complication of bacterial

meningitis. Complicated and basilar migraines may be

accompanied by neurologic symptoms, with alternating

hemiplegia attributed to basilar migraine in children.

Several conditions cause stroke in children. Heart

disease is the most common of these, responsible for

one-third of all ischemic infarctions in children. Right to

left (cyanotic) intracardiac shunts can cause

polycythemia, leading to thrombosis and embolism.

Congenital heart disease with valvular defects and/or

cardiomyopathies can lead to thrombus formation and

stroke. Another common cause is hematologic

disorders such as sickle cell disease which is

associated with multiple infarcts. Coagulation disorders

such as hemophilia and platelet disorders have an

increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage and stroke.

Homocystinuria, an uncommon autosomal recessive

disorder, leads to an increased tendency for thrombosis

as a result of endothelial damage from excessive

homocystine, thus leading to platelet aggregation and

thrombus formation. Inherited disorders of the blood

vessel wall can result in hemorrhage (AVM's,

aneurysms, tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis,

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, fibromuscular

dysplasia, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and Fabry

disease).

References

Riela AR, Roach ES. Etiology of Stoke in Children.

Journal of Child Neurology 1993;8:201-220.

Pavlakis SG, Gould RJ, Zito JL. Stroke in Children.

Advances in Pediatrics 1991:151-179.

Matsushima Y, Aoyagi M, Niimi Y, Masaoka H,

Ohno K. Symptoms and Their Pattern of Progression

in Childhood Moyamoya Disease. Brain &

Development 1990;12:784.

Rooney CM, Kaye EM, Scott M, Klucznik RP,

Rosman NP. Modified Encephaloduro-

arteriosynangiosis as a Surgical Treatment of

Childhood Moyamoya Disease: Report of Five Cases.

Journal of Child Neurology 1991;6:24-31.