Orbital Injury

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 6, Case 9

Brunhild Halm, MD, PhD

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

This is an 8 year old boy who was playing with his

brother who accidentally kicked him in the left side of

the face with his knee. The boy developed epistaxis

immediately after the injury and he complained of

intermittent double vision in his left eye. He did not

loose consciousness, but his parents noted increased

somnolence and 3 episodes of emesis.

Past medical history is negative.

Exam: VS T36.6, HR 90, RR 16, BP 137/83,

oxygen saturation 100% in room air. He is somnolent,

but easily arousable. Eyes: Visual acuity 20/25 OU.

There is no proptosis. There is ecchymosis and

swelling of his left lower eyelid. There is mild left

periorbital swelling but no obvious tenderness or step

off deformity on palpation. The cornea, lens and

anterior chamber are clear. There is no hyphema.

Pupils are equal and reactive. There is restricted

upward and downward gaze in his left eye, but normal

ab/adduction. EOM's are normal in the right eye.

Sensation in the distribution of the infraorbital nerve is

intact.

TM's clear, no blood. There is blood in his nares.

No septal swelling is noted. His pharynx is clear. His

neck is nontender with full range of motion. His chest

is clear to auscultation. Heart regular without murmurs.

Abdomen nontender with active bowel sounds. His

speech is normal. Deep tendon reflexes are normal.

His strength is normal.

A CT scan of the brain and orbits is obtained.

View CT scan.

The brain is normal. The CT cut shown is taken in

the axial projection (i.e., the long axis of his body is

perpendicular to the plane of the CT scanner) through

the orbits using a "bone window" contrast setting. The

black arrow points to the medial wall of the left orbit

which is fractured and pushed medially.

Additional coronal CT views are taken of the orbits

by hyperextending his neck so that the long axis of his

head is closer to being parallel with the plane of the CT

scanner. Since axial cuts are parallel with the floor of

the orbit, some fractures of the orbital floor are not well

visualized. By repositioning the patient so that the CT

cuts are perpendicular to the orbital floor, a fracture of

the orbital floor can be more accurately visualized.

View coronal CT cut.

The brain is normal. The CT cut shown is taken in

the axial projection (i.e., the long axis of his body is

perpendicular to the plane of the CT scanner) through

the orbits using a "bone window" contrast setting. The

black arrow points to the medial wall of the left orbit

which is fractured and pushed medially.

Additional coronal CT views are taken of the orbits

by hyperextending his neck so that the long axis of his

head is closer to being parallel with the plane of the CT

scanner. Since axial cuts are parallel with the floor of

the orbit, some fractures of the orbital floor are not well

visualized. By repositioning the patient so that the CT

cuts are perpendicular to the orbital floor, a fracture of

the orbital floor can be more accurately visualized.

View coronal CT cut.

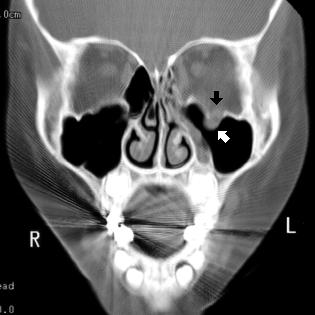

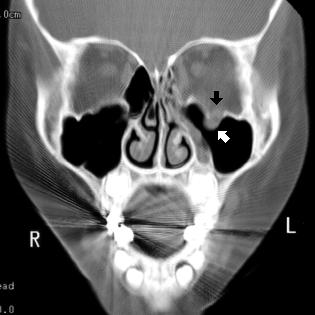

These coronal views reveal a fracture of the left

orbital floor (black arrow). The white arrow points to the

inferior rectus muscle protruding into the maxillary

sinus through the orbital floor fracture site. The clinical

findings suggest that there may be entrapment of the

left inferior rectus muscle, leading to restriction in

upward and downward gaze and diplopia when trying to

look in these directions. The small depressed fracture

of the medial wall of the left orbit with opacification of

the left ethmoid air cells is again visible.

Fractures of the orbital floor may be difficult to

visualize on an axial CT scan through the orbits since

the orbital floor is parallel to the plane of the scan.

Fractures are best seen when the fracture is

perpendicular or oblique to the plane of the scan.

Thus, when an orbital floor fracture is suspected, as in

trauma to the orbit, coronal scans of the orbit should be

obtained, provided that the patient can be positioned

properly.

Orbital wall fractures:

The orbital bones are very delicate and their

thickness is similar to that of an eggshell. Orbital wall

fractures most often occur in the orbital floor and

sometimes in the medial wall, because these are the

weakest regions of the bony orbit. The proximity of the

paranasal sinuses, nerves, vessels, extraocular

muscles, globe and other orbital structures predispose

them to a wide variety of possible damage from injury

producing orbital fractures.

An orbital blow out fracture refers to a fracture of the

orbital floor, usually without involvement of the orbital

rim. The impacting object typically has a diameter that

is larger than that of the orbital opening. Examples

include a fist, tennis ball, baseball, snowball or door

knob. The mechanism of a blow out fracture is

controversial. There are two main theories that are

likely: 1) The fracture results from a sudden increase in

intraorbital pressure when the globe is being pushed

posteriorly. 2) The fracture is the result of "buckling"

forces which are transmitted to the orbital bones by

transient deformity of the orbital rim.

An aide to the evaluation of children with orbital

fractures is the mnemonic HEADER:

Hyphema: Evaluate the child for bleeding in the

anterior chamber and for other intraocular injuries.

Emphysema: Orbital emphysema is due to a

fracture of the medial wall and/or inferior wall which

permits communication between the ethmoid sinus

and/or the maxillary sinus with the orbital contents. In

order to make the diagnosis of orbital emphysema

clinically, the orbit should be palpated for crepitus.

Subcutaneous air can be dramatic when the patient

blows his/her nose. Patients may notice eye swelling

when blowing their nose. Orbital emphysema may be

visible on a plain radiograph of the orbit. It is also

visible on CT scans.

Epistaxis: A fracture of the medial orbital wall can

result in a significant nose bleed.

Anesthesia or hypoaesthesia in the distribution of

the second branch of the trigeminal nerve must be

suspected in any fracture involving the infraorbital

canal. The distribution involves the lower eyelid and

the cheek down to the upper lip on the side of the

injury.

Diplopia: Double vision has essentially two primary

mechanisms: 1) A mechanical entrapment of an eye

muscle, most commonly, the inferior rectus muscle, or

the inferior oblique muscle. 2) A paralytic component

where injury to the third cranial nerve has occurred.

The third cranial nerve innervates both the inferior

rectus and the inferior oblique muscle. Hemorrhage

and edema within the extraocular muscles may also

cause transient paresis.

Exophthalmos is secondary to intraorbital

hemorrhage and edema which pushes the globe

anteriorly. However, a large fracture of the medial

wall or orbital floor may result in enophthalmos.

Restriction: Entrapment of extraocular muscles and

orbital tissue in the fracture site leads to decreased

ocular motility. With orbital floor fractures, the inferior

rectus muscle most commonly is entrapped leading to

limitation in upward gaze. With medial wall fractures,

limited abduction due to medial rectus incarceration

may result.

Diagnosis:

CT scanning is highly useful in the assessment of

orbital trauma and associated injures to the brain and

sinuses. Coronal views (direct or reconstructed) should

be requested when orbital trauma is present.

Plain radiographs are not sufficient. They may be

helpful in confirming fractures and in the delineation of

air-fluid levels in the paranasal sinuses, but they may

fail to show the existence and extent of orbital

fractures.

Surgical repair of a fractured orbital wall would be

indicated in the following instances: 1) Significant

enophthalmos. 2) Diplopia in primary gaze or in a

functional gaze. 3) Significant limitation of extraocular

movements.

References:

1. Levin AV. Eye trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine,

3rd edition. 1993, Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, pp. 1200-1209.

2. Mead MD. Evaluation and Initial Management of

Patients with Ocular and Adnexal Trauma. In: Albert

DM, Jakobiec FA (eds). Principles and Practice of

Ophthalmology. 1994, Philadelphia, Saunders, Volume

5, pp. 3362-3375.

3. Friendly DS, Jaafar MS. Ocular Trauma. In:

Eichelberger MR. Pediatric Trauma. 1993, St. Louis,

pp. 401-410.

These coronal views reveal a fracture of the left

orbital floor (black arrow). The white arrow points to the

inferior rectus muscle protruding into the maxillary

sinus through the orbital floor fracture site. The clinical

findings suggest that there may be entrapment of the

left inferior rectus muscle, leading to restriction in

upward and downward gaze and diplopia when trying to

look in these directions. The small depressed fracture

of the medial wall of the left orbit with opacification of

the left ethmoid air cells is again visible.

Fractures of the orbital floor may be difficult to

visualize on an axial CT scan through the orbits since

the orbital floor is parallel to the plane of the scan.

Fractures are best seen when the fracture is

perpendicular or oblique to the plane of the scan.

Thus, when an orbital floor fracture is suspected, as in

trauma to the orbit, coronal scans of the orbit should be

obtained, provided that the patient can be positioned

properly.

Orbital wall fractures:

The orbital bones are very delicate and their

thickness is similar to that of an eggshell. Orbital wall

fractures most often occur in the orbital floor and

sometimes in the medial wall, because these are the

weakest regions of the bony orbit. The proximity of the

paranasal sinuses, nerves, vessels, extraocular

muscles, globe and other orbital structures predispose

them to a wide variety of possible damage from injury

producing orbital fractures.

An orbital blow out fracture refers to a fracture of the

orbital floor, usually without involvement of the orbital

rim. The impacting object typically has a diameter that

is larger than that of the orbital opening. Examples

include a fist, tennis ball, baseball, snowball or door

knob. The mechanism of a blow out fracture is

controversial. There are two main theories that are

likely: 1) The fracture results from a sudden increase in

intraorbital pressure when the globe is being pushed

posteriorly. 2) The fracture is the result of "buckling"

forces which are transmitted to the orbital bones by

transient deformity of the orbital rim.

An aide to the evaluation of children with orbital

fractures is the mnemonic HEADER:

Hyphema: Evaluate the child for bleeding in the

anterior chamber and for other intraocular injuries.

Emphysema: Orbital emphysema is due to a

fracture of the medial wall and/or inferior wall which

permits communication between the ethmoid sinus

and/or the maxillary sinus with the orbital contents. In

order to make the diagnosis of orbital emphysema

clinically, the orbit should be palpated for crepitus.

Subcutaneous air can be dramatic when the patient

blows his/her nose. Patients may notice eye swelling

when blowing their nose. Orbital emphysema may be

visible on a plain radiograph of the orbit. It is also

visible on CT scans.

Epistaxis: A fracture of the medial orbital wall can

result in a significant nose bleed.

Anesthesia or hypoaesthesia in the distribution of

the second branch of the trigeminal nerve must be

suspected in any fracture involving the infraorbital

canal. The distribution involves the lower eyelid and

the cheek down to the upper lip on the side of the

injury.

Diplopia: Double vision has essentially two primary

mechanisms: 1) A mechanical entrapment of an eye

muscle, most commonly, the inferior rectus muscle, or

the inferior oblique muscle. 2) A paralytic component

where injury to the third cranial nerve has occurred.

The third cranial nerve innervates both the inferior

rectus and the inferior oblique muscle. Hemorrhage

and edema within the extraocular muscles may also

cause transient paresis.

Exophthalmos is secondary to intraorbital

hemorrhage and edema which pushes the globe

anteriorly. However, a large fracture of the medial

wall or orbital floor may result in enophthalmos.

Restriction: Entrapment of extraocular muscles and

orbital tissue in the fracture site leads to decreased

ocular motility. With orbital floor fractures, the inferior

rectus muscle most commonly is entrapped leading to

limitation in upward gaze. With medial wall fractures,

limited abduction due to medial rectus incarceration

may result.

Diagnosis:

CT scanning is highly useful in the assessment of

orbital trauma and associated injures to the brain and

sinuses. Coronal views (direct or reconstructed) should

be requested when orbital trauma is present.

Plain radiographs are not sufficient. They may be

helpful in confirming fractures and in the delineation of

air-fluid levels in the paranasal sinuses, but they may

fail to show the existence and extent of orbital

fractures.

Surgical repair of a fractured orbital wall would be

indicated in the following instances: 1) Significant

enophthalmos. 2) Diplopia in primary gaze or in a

functional gaze. 3) Significant limitation of extraocular

movements.

References:

1. Levin AV. Eye trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine,

3rd edition. 1993, Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, pp. 1200-1209.

2. Mead MD. Evaluation and Initial Management of

Patients with Ocular and Adnexal Trauma. In: Albert

DM, Jakobiec FA (eds). Principles and Practice of

Ophthalmology. 1994, Philadelphia, Saunders, Volume

5, pp. 3362-3375.

3. Friendly DS, Jaafar MS. Ocular Trauma. In:

Eichelberger MR. Pediatric Trauma. 1993, St. Louis,

pp. 401-410.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

The brain is normal. The CT cut shown is taken in

the axial projection (i.e., the long axis of his body is

perpendicular to the plane of the CT scanner) through

the orbits using a "bone window" contrast setting. The

black arrow points to the medial wall of the left orbit

which is fractured and pushed medially.

Additional coronal CT views are taken of the orbits

by hyperextending his neck so that the long axis of his

head is closer to being parallel with the plane of the CT

scanner. Since axial cuts are parallel with the floor of

the orbit, some fractures of the orbital floor are not well

visualized. By repositioning the patient so that the CT

cuts are perpendicular to the orbital floor, a fracture of

the orbital floor can be more accurately visualized.

View coronal CT cut.

The brain is normal. The CT cut shown is taken in

the axial projection (i.e., the long axis of his body is

perpendicular to the plane of the CT scanner) through

the orbits using a "bone window" contrast setting. The

black arrow points to the medial wall of the left orbit

which is fractured and pushed medially.

Additional coronal CT views are taken of the orbits

by hyperextending his neck so that the long axis of his

head is closer to being parallel with the plane of the CT

scanner. Since axial cuts are parallel with the floor of

the orbit, some fractures of the orbital floor are not well

visualized. By repositioning the patient so that the CT

cuts are perpendicular to the orbital floor, a fracture of

the orbital floor can be more accurately visualized.

View coronal CT cut.

These coronal views reveal a fracture of the left

orbital floor (black arrow). The white arrow points to the

inferior rectus muscle protruding into the maxillary

sinus through the orbital floor fracture site. The clinical

findings suggest that there may be entrapment of the

left inferior rectus muscle, leading to restriction in

upward and downward gaze and diplopia when trying to

look in these directions. The small depressed fracture

of the medial wall of the left orbit with opacification of

the left ethmoid air cells is again visible.

Fractures of the orbital floor may be difficult to

visualize on an axial CT scan through the orbits since

the orbital floor is parallel to the plane of the scan.

Fractures are best seen when the fracture is

perpendicular or oblique to the plane of the scan.

Thus, when an orbital floor fracture is suspected, as in

trauma to the orbit, coronal scans of the orbit should be

obtained, provided that the patient can be positioned

properly.

Orbital wall fractures:

The orbital bones are very delicate and their

thickness is similar to that of an eggshell. Orbital wall

fractures most often occur in the orbital floor and

sometimes in the medial wall, because these are the

weakest regions of the bony orbit. The proximity of the

paranasal sinuses, nerves, vessels, extraocular

muscles, globe and other orbital structures predispose

them to a wide variety of possible damage from injury

producing orbital fractures.

An orbital blow out fracture refers to a fracture of the

orbital floor, usually without involvement of the orbital

rim. The impacting object typically has a diameter that

is larger than that of the orbital opening. Examples

include a fist, tennis ball, baseball, snowball or door

knob. The mechanism of a blow out fracture is

controversial. There are two main theories that are

likely: 1) The fracture results from a sudden increase in

intraorbital pressure when the globe is being pushed

posteriorly. 2) The fracture is the result of "buckling"

forces which are transmitted to the orbital bones by

transient deformity of the orbital rim.

An aide to the evaluation of children with orbital

fractures is the mnemonic HEADER:

Hyphema: Evaluate the child for bleeding in the

anterior chamber and for other intraocular injuries.

Emphysema: Orbital emphysema is due to a

fracture of the medial wall and/or inferior wall which

permits communication between the ethmoid sinus

and/or the maxillary sinus with the orbital contents. In

order to make the diagnosis of orbital emphysema

clinically, the orbit should be palpated for crepitus.

Subcutaneous air can be dramatic when the patient

blows his/her nose. Patients may notice eye swelling

when blowing their nose. Orbital emphysema may be

visible on a plain radiograph of the orbit. It is also

visible on CT scans.

Epistaxis: A fracture of the medial orbital wall can

result in a significant nose bleed.

Anesthesia or hypoaesthesia in the distribution of

the second branch of the trigeminal nerve must be

suspected in any fracture involving the infraorbital

canal. The distribution involves the lower eyelid and

the cheek down to the upper lip on the side of the

injury.

Diplopia: Double vision has essentially two primary

mechanisms: 1) A mechanical entrapment of an eye

muscle, most commonly, the inferior rectus muscle, or

the inferior oblique muscle. 2) A paralytic component

where injury to the third cranial nerve has occurred.

The third cranial nerve innervates both the inferior

rectus and the inferior oblique muscle. Hemorrhage

and edema within the extraocular muscles may also

cause transient paresis.

Exophthalmos is secondary to intraorbital

hemorrhage and edema which pushes the globe

anteriorly. However, a large fracture of the medial

wall or orbital floor may result in enophthalmos.

Restriction: Entrapment of extraocular muscles and

orbital tissue in the fracture site leads to decreased

ocular motility. With orbital floor fractures, the inferior

rectus muscle most commonly is entrapped leading to

limitation in upward gaze. With medial wall fractures,

limited abduction due to medial rectus incarceration

may result.

Diagnosis:

CT scanning is highly useful in the assessment of

orbital trauma and associated injures to the brain and

sinuses. Coronal views (direct or reconstructed) should

be requested when orbital trauma is present.

Plain radiographs are not sufficient. They may be

helpful in confirming fractures and in the delineation of

air-fluid levels in the paranasal sinuses, but they may

fail to show the existence and extent of orbital

fractures.

Surgical repair of a fractured orbital wall would be

indicated in the following instances: 1) Significant

enophthalmos. 2) Diplopia in primary gaze or in a

functional gaze. 3) Significant limitation of extraocular

movements.

References:

1. Levin AV. Eye trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine,

3rd edition. 1993, Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, pp. 1200-1209.

2. Mead MD. Evaluation and Initial Management of

Patients with Ocular and Adnexal Trauma. In: Albert

DM, Jakobiec FA (eds). Principles and Practice of

Ophthalmology. 1994, Philadelphia, Saunders, Volume

5, pp. 3362-3375.

3. Friendly DS, Jaafar MS. Ocular Trauma. In:

Eichelberger MR. Pediatric Trauma. 1993, St. Louis,

pp. 401-410.

These coronal views reveal a fracture of the left

orbital floor (black arrow). The white arrow points to the

inferior rectus muscle protruding into the maxillary

sinus through the orbital floor fracture site. The clinical

findings suggest that there may be entrapment of the

left inferior rectus muscle, leading to restriction in

upward and downward gaze and diplopia when trying to

look in these directions. The small depressed fracture

of the medial wall of the left orbit with opacification of

the left ethmoid air cells is again visible.

Fractures of the orbital floor may be difficult to

visualize on an axial CT scan through the orbits since

the orbital floor is parallel to the plane of the scan.

Fractures are best seen when the fracture is

perpendicular or oblique to the plane of the scan.

Thus, when an orbital floor fracture is suspected, as in

trauma to the orbit, coronal scans of the orbit should be

obtained, provided that the patient can be positioned

properly.

Orbital wall fractures:

The orbital bones are very delicate and their

thickness is similar to that of an eggshell. Orbital wall

fractures most often occur in the orbital floor and

sometimes in the medial wall, because these are the

weakest regions of the bony orbit. The proximity of the

paranasal sinuses, nerves, vessels, extraocular

muscles, globe and other orbital structures predispose

them to a wide variety of possible damage from injury

producing orbital fractures.

An orbital blow out fracture refers to a fracture of the

orbital floor, usually without involvement of the orbital

rim. The impacting object typically has a diameter that

is larger than that of the orbital opening. Examples

include a fist, tennis ball, baseball, snowball or door

knob. The mechanism of a blow out fracture is

controversial. There are two main theories that are

likely: 1) The fracture results from a sudden increase in

intraorbital pressure when the globe is being pushed

posteriorly. 2) The fracture is the result of "buckling"

forces which are transmitted to the orbital bones by

transient deformity of the orbital rim.

An aide to the evaluation of children with orbital

fractures is the mnemonic HEADER:

Hyphema: Evaluate the child for bleeding in the

anterior chamber and for other intraocular injuries.

Emphysema: Orbital emphysema is due to a

fracture of the medial wall and/or inferior wall which

permits communication between the ethmoid sinus

and/or the maxillary sinus with the orbital contents. In

order to make the diagnosis of orbital emphysema

clinically, the orbit should be palpated for crepitus.

Subcutaneous air can be dramatic when the patient

blows his/her nose. Patients may notice eye swelling

when blowing their nose. Orbital emphysema may be

visible on a plain radiograph of the orbit. It is also

visible on CT scans.

Epistaxis: A fracture of the medial orbital wall can

result in a significant nose bleed.

Anesthesia or hypoaesthesia in the distribution of

the second branch of the trigeminal nerve must be

suspected in any fracture involving the infraorbital

canal. The distribution involves the lower eyelid and

the cheek down to the upper lip on the side of the

injury.

Diplopia: Double vision has essentially two primary

mechanisms: 1) A mechanical entrapment of an eye

muscle, most commonly, the inferior rectus muscle, or

the inferior oblique muscle. 2) A paralytic component

where injury to the third cranial nerve has occurred.

The third cranial nerve innervates both the inferior

rectus and the inferior oblique muscle. Hemorrhage

and edema within the extraocular muscles may also

cause transient paresis.

Exophthalmos is secondary to intraorbital

hemorrhage and edema which pushes the globe

anteriorly. However, a large fracture of the medial

wall or orbital floor may result in enophthalmos.

Restriction: Entrapment of extraocular muscles and

orbital tissue in the fracture site leads to decreased

ocular motility. With orbital floor fractures, the inferior

rectus muscle most commonly is entrapped leading to

limitation in upward gaze. With medial wall fractures,

limited abduction due to medial rectus incarceration

may result.

Diagnosis:

CT scanning is highly useful in the assessment of

orbital trauma and associated injures to the brain and

sinuses. Coronal views (direct or reconstructed) should

be requested when orbital trauma is present.

Plain radiographs are not sufficient. They may be

helpful in confirming fractures and in the delineation of

air-fluid levels in the paranasal sinuses, but they may

fail to show the existence and extent of orbital

fractures.

Surgical repair of a fractured orbital wall would be

indicated in the following instances: 1) Significant

enophthalmos. 2) Diplopia in primary gaze or in a

functional gaze. 3) Significant limitation of extraocular

movements.

References:

1. Levin AV. Eye trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine,

3rd edition. 1993, Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, pp. 1200-1209.

2. Mead MD. Evaluation and Initial Management of

Patients with Ocular and Adnexal Trauma. In: Albert

DM, Jakobiec FA (eds). Principles and Practice of

Ophthalmology. 1994, Philadelphia, Saunders, Volume

5, pp. 3362-3375.

3. Friendly DS, Jaafar MS. Ocular Trauma. In:

Eichelberger MR. Pediatric Trauma. 1993, St. Louis,

pp. 401-410.