Many who are familiar with Lahaina town on Maui will tell you that walking down Front Street can be like traveling through history. The catastrophic August 2023 deadly wildfire claimed structures and landmarks connected to the area’s storied whaling era, the 1820s arrival of the missionaries and the plantation period, which stretched from one end of the iconic street to the other.

Historians at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa recall the area’s significance even farther back in time during the days of Native Hawaiian kings and flourishing kalo terraces.

Related: Rebuilding, preserving Lahaina’s historic district.

“It’s an area that carries deep, deep mana (power), it’s a central place of mana for the island. It’s where our aliʻi resided and we trained the leaders of the kingdom,” said Ty Kāwika Tengan, ethnic studies and anthropology professor at UH Mānoa.

Despite the English translation of Lahaina to cruel sun, said to stem from ongoing drought, early explorers describe it as teeming with fresh waterways and verdant manicured fields of ʻulu (breadfruit) and ʻuala (sweet potato).

Royal island

From 1837 to 1845, King Kamehameha III lived on the tiny island of Mokuʻula surrounded by a 17-acre pond in the heart of the area. Under his rule, Lahaina became the official first capital of the constitutional monarchy that set the foundation for judicial and executive branches of government.

Traditionally called Lele, the West Maui district was favored by aliʻi (royalty) for its abundance of food from ʻāina (land) and kai (ocean), and balanced climate. Geographically, it also served as an integral lookout for intruders.

More on how to help Maui ʻohana and the Maui wildfires.

“It’s sort of the seat of power and it’s a good vantage point. You can see all the islands that are a part of Maui Nui,” said Kalei Nuʻuhiwa, a lecturer at Hawaiʻinuiākea and native of Lahaina. “You can see if anyone is coming from Hawaiʻi Island, very easily. It’s hard to sneak up on people.”

For generations, Nuʻuhiwa’s ʻohana (family) were caretakers of Mokuʻula long before the island that once housed Hawaiian royalty was eventually buried under a modern-day baseball field.

Royal resting place

The 200-year-old Waiola Church is among hundreds of structures destroyed in the Lahaina wildfires. Founded by Keōpuōlani, the mother of King Kamehameha II and III, it’s the parish where Christianity began on Maui.

Keōpuōlani combined forces with Kaʻahumanu (Kamehameha I’s favored wife) to convince Kamehameha II to eliminate ancient religion and the kapu system, a traditional Hawaiian code of conduct of laws and regulations.

“Kaʻahumanu had accepted Christianity and converted to Christianity wholeheartedly. She was so enthusiastic about Christianity, she made the Ten Commandments law and enforced it,” said Davianna Pomaikaʻi McGregor, a UH Mānoa ethnic studies professor emerita. “People were arrested and sentenced to go to Kahoʻolawe for adultery.”

Keōpuōlani rests at Waiola Church’s graveyard alongside notable aliʻi such as her daughter, Princess Nāhiʻenaʻena and Kaumualiʻi, the last reigning king of Kauaʻi.

Educating Hawaiʻi’s future leaders

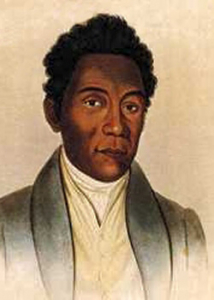

Founded in 1831, early missionaries opened Lahainaluna School, which was put under direct control of the Hawaiian monarchy. Currently a public secondary school, at the base of Puʻu Paʻupaʻu (Hill of Struggle) in Lahaina, the institution is the oldest high school west of the Mississippi River and facilitated the education of renowned scholars and government leaders in Hawaiʻi’s Kingdom. Among its most renowned graduates is Native Hawaiian politician, educator and author David Malo, who is still praised today for his accounts of ancient Hawaiian practices, religious beliefs and legends documented in his book, Hawaiian Antiquities.

Lahainaluna also printed the first newspaper west of the Rockies, Ka Lama (The Torch). It was also the first newspaper printed in the Hawaiian language. This kickstarted a massive movement from 1834 to 1948, when more than 100 independent newspapers were printed in Hawaiian.

- Related UH News story: Native Hawaiian newspapers of the past reveal destruction of 1871 hurricane, April 4, 2018

Last fall, the UH Center for Oral History (COH) launched a special project interviewing Native Hawaiians who were enrolled in the school’s boarding program from the 1950s to 1990s. Since last year, Tengan’s team has connected with Lahainaluna graduates who still recall the generosity of Lahaina residents.

“They shared a deep love and connection for the school and the people of Lahaina who took them in,” said Tengan. “They relied on a classmates’ family who would take them in for the weekend. Many of them shared how loving and how open families in Lahaina were.”

Tengan said given the tragic events that wiped out much of the beloved town, the mission to complete the Center’s Lahainaluna Boarders project is now more important than ever.

Upon completion, interviews will be made public on COH’s website.

—By Moanikeʻala Nabarro