Letter to Tangata

Va ‘Ofi in the Tongan Mormon Family

Dear Tangata,

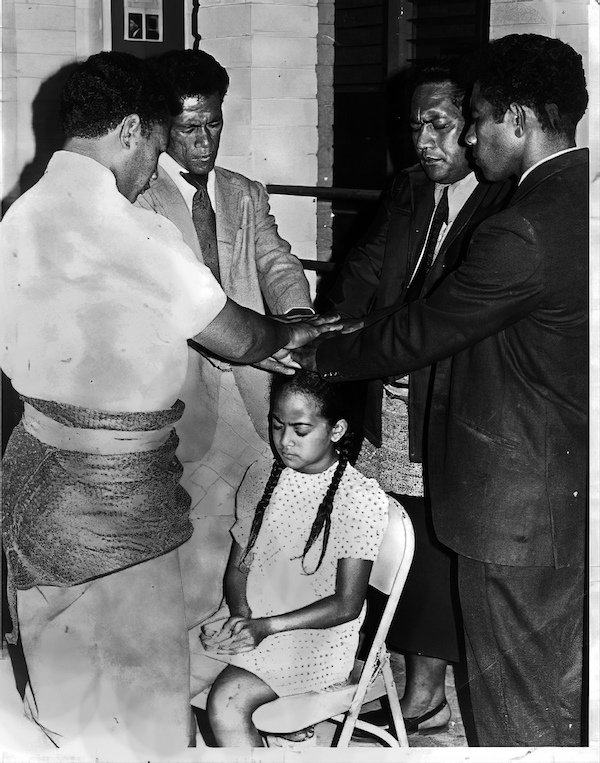

Remember that photograph taken shortly after you came back home?

Our patchwork of dreams had come true. Tangata, we were a family, once again.

The photograph memorializes my Mormon baptism that took place shortly after my eighth birthday at the Mormon chapel located in Ma‘ufanga. In the photo, I am wearing a white dress with blue polka dots that was sewed specifically for this important day. I am sitting on a metal foldout chair with my eyes closed and my small head fervently bowed in prayer.

I am surrounded by a circle, a formidable circle that consisted of Tongan men, Tongan patriarchs that held the authority of the Mormon Melchezidek Priesthood. You and three other Tongan men encircle me with your large brown bodies and your hands nestled gently on my small head. Three uncles; one, two, three, and there you are, my beloved father, Tangata, standing behind me offering a “father’s blessing.”

A few days earlier, Litia, my mother, told me the good news and we waited to tell you until you got back home from your new job as a Tongan language translator for the Mormon Church. You were overwhelmed and you had to sit down. You were recently bestowed to the office of the Melchizedek Priesthood. This new authority allowed you to participate in the circle of men and to offer me, your first-born daughter, a father’s blessing at “the ordinance of confirmation” ceremony at my baptism into the Mormon Church.

My baptism symbolized the many new changes in our home and it also revealed the promises and dreams that the future held for our family. Joy swept over our home like warm tides of salt water. That night all of us; you, Litia, Loa, baby ‘Amelia and me, participated in rituals that were previously unknown to us. We laughed together and we held each other and cried, grateful for the many new blessings in our lives and the promises that they offered. We were a family once again. We ate sapa, as we called the evening meal as kids in Tonga, and Loa and I sang along to our favorite ballad, Linda Rondstandt’s “Blue Bayou” on A3Z radio, “I’ll never be blue, my dreams come true on Blue Bayou.”

It was only a few months ago, Loa and I wept when we saw you nestled in the small bed at Vaiola Hosptial with needles, pipelines and sharp wires prodding endlessly into the veins of your frail body. Your Alcoholism had stolen everything except for the suffering brought by the tuberculosis. Your vibrant body grey with fever. It was at that moment when you tasted the veracity of death that you made a commitment to stay alive. When Litia introduced you to the smiling American missionaries with white button up shirts touting their Book of Mormon and the Mormon church offered you a lucrative new job as a Tongan language translator at their new office in Ma‘ufanga, you reluctantly accepted and agreed to conversion and baptism. Your choices were limited, Tangata. You lost your coveted government job as a Tongan language translator for the Tongan courts and the circle of hou‘eiki family, Western educated friends that had once embraced you, now remember you with pity.

But the American Mormon Gods picked you up and they breathed a new life into your lungs and in return, you vowed never to forget. You spent your new life effusively thanking and praising the Mormon Church and their new Mormon God for saving your life and bringing you salvation. You were the Prodigal Son and the White Mormon Father welcomed you back home. You sang praises to the Mormon God for many, many years until they forced you into early retirement from your Tongan language translation job at the Mormon Church headquarters in Salt Lake City, Utah many decades later after our family moved our lives from our home and relatives in Tongatapu to the small, white, xenophobic and working-class town, Orem, located in the state of Utah. Your early and unexpected retirement from your translation job broke your heart. It was yet another institutional reminder of your “smallness” in their eyes, but you kept your promise to them and although you never explicitly criticized the Mormon Church, you were not as grateful and obedient as you once were.

Tangata, when I was a child, I was often awakened by a recurring nightmare of a heinous giant like the one in the children’s story, Jack and the Bean Stalk that Litia often read to us before bed. In the threads of my nightmare, the Giant threatened to break down the walls of our Kolomotu’a home and he aimed to tear Loa and me into pieces. But just before the giant’s gigantic fingers caught us, you lifted us up to safety then I abruptly woke up and I immediately began embarking on another arduous task that I did often during that time in our lives. I always searched for you, scanning the darkness for clues that will lead me to you. Searching for you like I often did on those monsoon cold nights when Litia packed Loa and I in our small brown car and drove us to the front door of the Tongan Klub in downtown Nuku‘alofa.

Wives were not allowed at the Tongan Klub. The stories circulated around Nuku‘alofa telling about the “bad” Tongan wives that dared to enter the doors of the Tonga Klub to lure their husbands back home. As the stories tell, these wives were publicly beaten inside the Tongan Klub by the hands of their husbands until their faces were maimed by bruises and cuts and were often unrecognizable to their young children waiting at home. It was one of the many reminders that Tongan women must always remember “their place.”

Tangata, but I was a child and not easily detected in the darkness and as the saying goes, even drunk men can feel a sliver of mercy for a crying child. It was often my responsibility to enter through the front door of the Tonga Klub and to bring you back home. I often entered the front door, past the surprised faces and gasps and with wide open eyes, I scanned the darkness, looking past the long rows of inebriated men, many of whom were palangi expats and diplomats, Tongan men with Western education, some hou‘eiki and many with Tongan government jobs. Many of the men were familiar, either relatives or uncles. Most of the men at the Tonga Klub were fathers, just like you, with tired wives and young children just like me, holding their breaths and waiting for their fathers to return back home.

Yes, Tangata, but that was a past and why cry over the past when this present space and time was different and we all dreamt a new future far away from the past. My eyes scan the acres of darkness but this time around, I am able to quickly find you, locate you, yes there you are, snoring and deep in sleep next to my mother, Litia, in our small one bedroom home on Hala Sipu in Kolomotu‘a. The house is quiet. Everyone is asleep and we will wake up early to go to Church services at the Mormon Church located in Kolomotu‘a tomorrow morning. I was able to find my breath again; the heinous Giant will never hurt Loa or me again. You have returned home.

Tangata, in the photograph, you surround me. I am a young girl with a bowed head and your large hand surrounds me, you are a circle that envelope me, a formidable circle of Tongan men bestowed with the Priesthood. You are a part of a circle of Tongan patriarchs, a Tongan Mormon patriarchal circle, there are four of you, familiar, and related to me, uncles on your side and/or through Litia’s side, one, two, three and yes, there you are my beloved father, Tangata, with your head bowed in prayer,

Tangata, in the Tongan Mormon patriarchal circle, you began the blessing by calling out my full names, the many names, old Tongan names that remember and trace the cycles of ancestral va from Ha’apai, Vava’u circling to embrace our relatives in Havaiki and then back to our current home in Hala Sipu. And yet in the Mormon patriarchal circle that surround me, my name, the old names, the names of our beloved Tongan ancestors, titles of powerful women leaders, women that were heads of families, Tongan female warriors, beloved sisters and mothers, stumble and they fall out of place, tangled, like catching the past on a new global map that only turns its face forward.

Our Tongan names fall out of place, tangled, they become Other. Like when we migrated to the predominantly white and Mormon town, Provo, Utah after our baptism into the Mormon Church so that you and Litia could attend Brigham Young University. It was my first day at Ferrer Jr High School in Provo, Utah and after a long day of filling out paper work, paying fees with money we didn’t have and after hours of being stared-at by white faces reminding us of our second class status, you quietly took me aside and asked me if I wanted to change my name to Francis, Fran, Frannie or something that was more familiar for the palangi and easier for them to pronounce. We shortened my first name Fuifuilupe to Lupe. Lupe is the Tongan word for dove. Lining up my names and slicing them into compartments was like severing the wing of a still breathing bird. Lupe was designated as my new school name because you believed it was going to be much easier on the palangi tongue and in return for our sacrifice, you hoped that the palangi would go easy on their treatment of us.

Our old Tongan names stumble and fall as if out of place, tangled, like catching the past on a new global map that only turns its face forward.

Tangata, standing in the Tongan Mormon patriarchal circle, you taught me the politics of desire. You taught me how and what to desire. You reminded me that my role was to marry a man with the Priesthood and to become a good wife. Your deep voice was filled with hope and dreams for the future of our family and with your new Priesthood authority, you confirm me as a member of the Mormon Church. You relayed the laws and its promises, the promises were the dreams we shared. If I obeyed and followed the laws of the Mormon Church, happiness would ensue.

I was committed to the dreams. I vowed to be a good daughter in our family and to do my part to make the dreams come true. I vowed to obey the laws of the Mormon Church so that this time you would stay, so that this time around, you would choose us—Loa, Baby ‘Amelia, Litia and me—so that we would be a family, once again, and like the Mormon church leaders’ promised us, we would be a family, forever for time and for all eternity.

My beloved father, it’s been five years since your death. Your legacy is one that I attempt to confront, hold and mourn here in the space of this historical archive. I still remember the panic that struck me when Loa came to give me the news of your death. I knew the news before she said anything. Loa and I were in a crowded room and I began running in circles away from her reach, as if we were children, once again, at Tonga Side School playing a game of hide-go-seek after school with the rich half-caste palangi kids while waiting for you, Tangata, to pick us from school like you often did when you first returned back home. But on that afternoon in Berkeley, California, Loa caught me, abruptly. “Fui, stop. You already know what I’m going to tell you. Stop.” You passed away in your sleep in your own bed in Sandy, Utah in the Summer of June, 2013. Although I had prepared myself for this news for many years after first hearing about your cancer diagnosis, the shock was still sharp as if I was hearing it for the first time.

I had just finished giving a presentation in a conference panel on political activism. I talked about the work that Loa and I do with queer Pacific Islander communities in the Bay Area, California. Loa and I helped to found a Pacific Islander queer women’s organization called OLO; One Love Oceania, an Indigenous Pacific Islander feminist response to the mainstream Pacific Islander Community’s ardent support for California’s Prop 8.

Most of the support for Prop 8 was orchestrated by white Mormon Church leaders from their privileged positions in Salt Lake City. OLO’s aim was to speak out against homophobia in our Pacific Islander families and communities and we denounced the mainstream’s racist representations of Tongan and Pacific Islander communities as “essentially” homophobic and misogynist.

The mainstream media’s imagery of Tonganness was enticing. The big brown bodies of our Tongan men were militarized and used as weapons to police Mormon temples from Oakland, San Diego reaching all the way to LA. Tongan male bodies were deployed as borders to draw lines of separation from the crowds of gay rights activists. The images were depicted matter-of-factly as if they were true. As if Tonganness is a spatiality devoid of gay or queer. The mainstream media fed us endless images but one in particular still haunts me. The image portrayed in the LA Times depicts volatile Tongan male rage vying on a national stage against a small and white lesbian woman. This image still breaks my heart. What was not shown was the wealthy white male Mormon Church leaders issuing the orders while sitting behind desks in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Yes, Tangata, my life here in Huichin, the Ohlone name for the East Bay, California, is far from my life growing up under your heavy hand and the oppressive hand of the Mormon Church in Tonga, Hawai’i, and Utah.

How do I stop all this running so that I can identify and count the losses, touch the broken pieces, the dreams, oh the many dreams with edges that never coalesced?

In the photograph, we are a family, once again. You’ve returned back home Tangata. Your large hands nestled on my young 8-year-old head used to offer the “father’s blessing” in the Mormon patriarchal circle are the same hands that I feared because you often used them as weapons to terrorize me. You used your hands and your new Priesthood authority to create a landscape dominated by violence and fear and to enforce the new laws of patriarchy in our home. I was always reminded through violence or the threat of violence that as your daughter and as a woman in our family, my only options were obedience and silence to the laws of the Priesthood.

Tangata, as you know well, I worked hard to be obedient and to be the “good Tongan Mormon daughter” in our family, the many scholarships, academic and community awards and recognition, the numerous church callings, etc., but my contributions were never enough. Tell me what does a Tongan Mormon daughter do when obedience fails her? What does a Tongan Mormon daughter do when obedience and silence can no longer sustain her?

Tangata, I spent my life searching for you. I looked for acceptance, warmth, and for renditions of what I thought was love in the hands of men that were familiar for they resembled the Tongan Mormon patriarchal circle. Many of them were Priesthood holders and just like you, they used their large hands not only to show generous acts of compassion but their hands were used as weapons to create multiple forms of violence on my body and spirit to remind me that my role as a woman was limited to obedience and silence. These men, many of them lovers, followed cycles of the familiar; they followed the examples of violence against women passed down from father to son that they witnessed within the spatiality of their respective Tongan Mormon Families and Tongan community. The familiarity of violence shaped the va, the relationalities of intimacy we shared, the ways that we cared, desired and loved each other as Tongans.

It’s been five years since you passed away Tangata, and I still mourn your loss every day. Your spirit visits me, awakens me at night, tells me funny jokes and we laugh and laugh and eat sweets until morning. You sit with me as I weep and unravel the painful narratives on the table. You listen as I shout and yell and you tell me, “Si’i Fuifuilupe, please tell the stories. Tell the stories so that you can heal, tell the stories so that we can both heal. Tell the stories so that we can be free.”

Yes, ours is a complicated and often painful history. Yet, you have always been my hero, my beloved father, Tangata.

Tangata, thank you for embarking on a different type of homecoming this time around. Thank you for returning back home to mentor me so that I can attempt to tell these stories that we hold, collectively, because ours is a va that continues to breathe and thrive even after death. Ours is a va that is invariably connected to a commitment and love for each other, for our ancestors and for healing the wounds of our Tonganness.

‘ofa lahi atu from your loving daughter,

Fuifuilupe ‘Alilia Funaki Toutai

Journal Entry: Short Story of the Sacred

Dear Journal,

What happens to the spirits of our Tongan ancestors, our Tongan Sacred, once they are cast as criminal and forgotten? What happens to the spirits of our ancestors after we have severed va with them and cast them from our homes, erased them from the flesh bodies of salt water that archive our memories? Do the spirits sleep meekly and keep their mouths sliced shut like good Christians for the duration of centuries? Do they live inside the prison walls of our Tongan amnesia, within the complicity of our silence, or do the spirits of the dead, our Tongan ancestors, our Tongan Sacred, grow weary of loneliness,

do they become angered by the encroaching monsoons, waters growing into acres aching without end, floods of mourning created by the hands of European and U.S. greed, and militarization, courting the native as if we were ever consensual lovers

oh the seduction of surrender,

falling on their knees in prayer to new white Male Gods, rows stacked like missiles of friendly Tongan faces, missionaries, academics and businessmen that recite the alphabet of white “progress” on the decapitated bodies of Tongan women.

There is a taste that lingers, aroused, a flesh of memory that the colonizers are unable to mine, although they tried and tried and tried

it keeps refuge for centuries inside the salted corridors of my copious Tongan woman thighs, rain water, vai melie, sweet water, the black sand caves of ‘Oholei are moist with the young leaves of si, mohokoi, ripe fekika fruit, saplings of kape, taro, ‘ufi and manioke, enough to feed generations, kava root and koloa offered to the female God Felehune, our mother, circles of octopus body, generous like Ceremony circling the heartbeat of our Moana Nui tracing va, genealogies from Havaiki to the shores of Sogorea Te, the Ohlone Sacred Site, the occupied land now known as Vallejo, California.

Yes, let me reach inside this darkness, po‘uli, night, vai tafe tafe, water trickling, crooning without end, touch the heartbeat of Tonganness, our Sacred, the beginning that leads me to tell you the ending of this story

the spirits of our Tongan ancestors, our Tongan Sacred, the old ones, names of those of us that were criminalized, raped, killed and forgotten, the names of Tongan women warriors,

they and we

steal the Mormon missionaries’ matches and kerosene and burn down these Mutha Fucken prison walls!

September 8, 2019

Oakland California, Occupied Ohlone Land

Fuifuilupe Niumeitolu is a Tongan scholar and community organizer. She recently filed her PhD dissertation, The Mana of the Tongan Everyday: Tongan Grief and Mourning, Patriarchal Violence, and Remembering Va at the University of California, Berkeley, in May 2019. She is on the founding committee of the Moana Nui Pacific Islander Climate Justice Project and Oceania Coalition of Northern California (OCNC), community organizations working for Pacific Islander self determination through land justice, facilitating Ceremony with Pacific Islander prisoners in Northern California as well as working with California American Indian tribes to protect Indigenous Sacred spaces in California and in the Pacific. Fui hosts a radio segment titled “From Moana Nui to California; Indigenous Stories of Land” on 94.1 KPFA radio. She is currently working with the Sogorea Te Land Trust, an Urban Indigenous women’s land trust located in Oakland, California.