Rethinking Rapa Nui

Work by a UH archaeologist sheds new light on the history of this mysterious island

Artwork related to the birdman cult, associated with post-moai governance

The island’s oldest moai watches over the tent-shaded dig near Anakena Beach, where the first inhabitants settled, and a replanted palm grove that serves as present-day picnic grounds

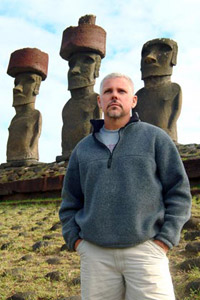

Terry Hunt’s research on moai, like the late-design top-knotted giants at Ahu Nau Nau, has scientists reconsidering the origin of Rapa Nui’s people and the role of the giant stone statues

A Rapanui woman, in white, and UH students examine a manavai built to provide shelter from the wind on the rugged and remote northwest coast

Students measure a fallen moai that lies face down along one of four roads leading from the quarry

Students measure a fallen moai that lies face down along one of four roads leading from the quarry

At the bottom of an 8-foot-deep pit, teaching assistant Kelley Esh shovels sandy brown earth into a bucket. With a grunt, she hoists the heavy container to the waiting hands of another worker on a ladder. Several students painstakingly sift through the bucket’s contents, unearthing chunks of animal bone, charcoal and obsidian; others sort and record the findings in a log. Nearby, a young Rapanui boy playfully gallops his horse across the shifting sand and several people picnic in a grove of palm trees. Silently observing it all, gigantic stone moai of Rapa Nui stand guard as they have for more than a thousand years.

"This island is one of the archaeological treasures of the world," reflects UH Mānoa Associate Professor of Anthropology Terry Hunt, who has organized this field class for the past three summers.

"We’re looking at the oldest intact archaeological deposit on the island. We’re the first ones to touch something that the original people here touched and used. We’re gathering the evidence to find out what those people were doing, and it’s telling a very different story."

Digging at Anakena Beach, the landing and settlement site of Rapa Nui’s first inhabitants, Hunt’s team has found dolphin and seal bones as well as pieces of obsidian once fashioned into tools. But the most surprising find has been an abundance of rat bones.

Not just any rat, according to Hunt, but tiny, furry Polynesian rats brought here as an alternative food source by the original settlers. The rats, says Hunt, played a significant role in Rapa Nui’s history, a role that until recently has been overlooked.

History and Mystery

About the size of Kahoʻolawe, the 64-square-mile island of Rapa Nui lies alone in the Pacific Ocean at a remote corner of the Polynesian triangle—4,300 miles south of Hawaiʻi and roughly 2,500 miles equidistant from Tahiti to the west and the South American continent to the east. Since the Easter Sunday 1722 visit by Dutch explorer Admiral Jacob Roggeveen (hence the Easter Island name) Rapa Nui has intrigued the rest of the world. Where did the Rapanui people come from? How did they get to this isolated spot? Who built the mammoth stone statues and how were they moved?

Over the years, theories have come and gone, including outlandish claims involving outer-space aliens and the lost continent of Mu. In 1947, adventurer Thor Heyerdahl sailed the Kon-Tiki raft from Peru to Polynesia in an attempt to prove that Pacific Islands such as Easter were originally settled by Incas from South America.

Since then, studies of language, DNA, oral histories and archaeological findings indicate that seafaring Polynesians, not Incas, inhabited Rapa Nui. They arrived around 700 AD, probably from the Austral Islands in what is now French Polynesia.

As for the moai—those stern-faced statues said to represent a revered chief or ancestor, a visit to the island’s Rano Raraku quarry provides proof enough of their origins. Enormous stone carvings weighing an average of 25 tons each lie about in various stages of completion. Some are still attached to their volcanic womb. Others need only finishing touches. Still others stand expectantly at the quarry's base, waiting for a moving day that will never arrive. An exhibit at Rapa Nui’s Sebastian Englert Museum displays tools used to carve the behemoths: crude and dull-edged basalt chisels, one of the few implements available to a stone-age society.

It’s commonly believed that during 900 years of moai building, the Rapanui people chopped down all the island’s trees, using them as rollers or support beams to transport each moai across the island to its ahu (ceremonial platform). The lack of trees supposedly led to declining food production, warfare, cannibalism and near annihilation.

By 1877 only 111 Rapanui remained from an estimated, late-prehistoric population of 10,000. But the culprit "was not a mania for moai," Hunt points out. Moai building stopped more than a hundred years before Roggeveen’s arrival. Yet according to the admiral’s log, even without most of their trees the island’s inhabitants appeared well-fed and thriving. Less than 160 years later, the Rapanui found themselves near extinction thanks in large part to diseases introduced by sailors on whaling ships, a smallpox epidemic and slave trade that carried off Rapa Nui’s king, priests and civilians to labor in Peru.

What about the rats? "The Rapanui may have chopped down trees to move the moai," says Hunt, "but the growing number of rats played a part in deforestation. As recent work in Hawaiʻi shows, rats have an appetite for seeds that are the hope of the next generation of trees." Including, he adds, the coconut-flavored nut of the Jubaea palm, once one of Rapa Nui’s most plentiful species. Without seeds, new trees couldn’t grow.

Charcoal found at the beach dig also provides a clue to the island’s once treeless state. "Accidental fires could have taken much of the forest down," says Hunt, "and severe droughts may have contributed to the fire problem."

Build Moai and Prosper

Hunt also challenges the assumption that moai building created a food shortage. "Just the opposite," he insists. "According to evolutionary theory, if a civilization invests its energy into erecting giant statues or other cultural elaborations, its people have less energy for procreation and surplus food production. Thus by creating moai instead of offspring and the means to support them, the Rapanui kept their population down to a level that could be sustained by the island’s available resources. And they didn’t just survive, they prospered."

Even without trees, the Rapanui were able to adapt to their harsh environment using ingenuity and the one resource they had in abundance-rocks. On the island’s steep and rugged northwest coast, several of Hunt’s students measure manavai, circular enclosures made of stacked rocks that protected crops from the island’s pervasive winds. Some extend, like a patio garden, from hillside caves once used as shelter. Others are freestanding—rock circles amid a rock-strewn sea of tall grass.

On the way to a manavai site, Hunt stops at a moai that fell from its carrier during transport. How the massive moai were moved is still a mystery. A few theories have been tested with limited success, but "no one has ever systematically examined and documented the evidence to find out if these or other methods could have actually been used," says Hunt as he measures the moai’s size and the slope of the ground, records the giant’s position (face down, in this case) and takes a soil sample from beneath the moai for luminescence dating (measuring stored energy in minerals to determine when they were last exposed to sunlight).

The test provides a fairly accurate estimate of when the moai toppled off its transport vehicle. Aided by satellite imagery, Hunt and his students will locate and examine all the fallen moai along four ancient moai-transport roads leading from Rano Raraku quarry.

With plans to return again in the summer of 2005, Hunt is eager to fit together more pieces of the Rapa Nui puzzle. "Every little detail is a witness to what happened here," he says, "and we’re uncovering those details. I’ve spent so much time in the remains of the ancient peoples’ living areas that there’s a sense of how many of them were once here, like a ghost town. In a way it feels like they’re still here, watching us."

What happened to the trees?

The first western visitors to Rapa Nui found an island bare of native trees. But new research suggests Easter Island’s state had less to do with improvident actions of the inhabitants than with its fragile environment.

Writing in the Sept. 23, 2004, issue of Nature, Mānoa anthropologist Barry Rolett and a UCLA geographer identify nine variables that predispose a Pacific island to deforestation.

Like the equally barren Northwest Hawaiian Islands of Necker and Nihoa, Easter Island is old, low, dry and small—factors that reduce soil fertility and plant diversity. All three are located far both from trading partners (increasing dependence on local resources) and from sources of windborne dust or volcanic ash that can replenish soil nutrients. Pacific islands with more advantageous conditions and locations retained more of their tree cover.

Deforestation has been linked to societal decline. Rolett believes the environmental vulnerability model could help explain why Fertile Crescent and Mayan societies collapsed while Japan and highland New Guinea thrived. He and his colleague hope to further refine their analysis and test it on additional locations.