Through the opening months of 1938 a regular free-for-all ensued as organizers from the HWWA, the Sailor's Union of the Pacific (SUP) and the Marine Firemen, Oilers, Batertenders and Wipers Association (MFOWWA) wrestled each other for the ILWU and IBU Inter-Island workers. Finally, disgusted with the company delays and the resulting jurisdictional raids of the AFL's HWWA, the IBU struck Inter-Island the week of February 4th to force an end to the squabbles and demonstrate its true strength and support. Of the 215 crewmen on three ships, 180 walked off, and the matter was at last settled. In the end, Wilson was only able to pick up a handful of drydock workers, not otherwise represented by the Metal Trades Council.

With recognition issues out the way, the stage was finally set for the real negotiations to begin.

Part Two:

The Inter-Island Strike

As the bargaining began with a most reluctant employer, the three unions, the IBU, the ILWU and the MTC were in complete agreement on the two major issues: 1) parity or equity of wages and conditions with the West Coast workers; and 2) the closed or union shop or some kind preferential hiring arrangement.

But Hawai'i employers were committed to fight the issue of wage parity or mainland wage standards in every industry as a matter of principle. No matter how well their businesses were doing or how enormous the profits, the adamantly resisted the very notion that local workers should be compared to their mainland counterparts. That lower standard or pay in the standard of pay in the islands was jealously guarded as their competitive edge that would insure profitability through whatever economic times might lie ahead.

Inter-Island was having a particularly difficult time with this issue. The public was aware that the company's years of monopoly control of the light freight traffic had resulted in exorbitantly high rates. In the years previous to the strike, net profits and stock dividends generally exceeded 10%, while most local people felt that service was not particularly good and compared poorly to cheaper mainland lines.1

The question of wage parity, though, was somewhat different for the different I-I workers. At first glance, the seamen seemed to be making slightly more than some of the West Coast workers, but their working conditions were more severe, and resulted in an actual loss of take home-pay. On the West Coast, the seamen had a regular work week of 5 and a half days; the I-I men worked nine-hour days six or seven days a week with irregular and inconvenient hours at less than the overtime rates of their West Coast brothers. And on the Coast there were special premium rates for difficult or dangerous cargoes as well as meal and rent allowances, all of which left the I-I men lagging behind the mainland standard.2 For the Metal Trades workers the issue was more dramatic. The I-I drydock workers made 20% to 25% less than men doing the same work at Pearl Harbor.3

The second major issue, that of the preferential hiring hall was, like the wage issue, one that hinged on the ideas of recognition and dignity. Just as the unions were insistent that their work be given the same value and remuneration as mainland workers received, they also sought control over the greatest weapon the employers had used to fight the union. Since the early days of the movement, unionists had seen the employers' fire then blacklist their best organizers and representatives. Longshoremen in particular suffered from the shape-up hiring system whereby for each new shipment ready for unloading, all the workers, the veterans along with young new applicants, had to muster in a humiliating line-up like so much meat at an auction before the employer, hoping to be picked out. Sometimes they stood for hours, only to be turned away in the end; often they wasted the whole day for only an hour or two of paid work. More often than not men would try to improve their bid for work by tendering little bribes to the time keeper: Japanese sake during prohibition days, a chicken, or even a straight cut of their wages was likely to be required. Or, if a man were a good athlete, he stood a better chance of getting work since the company fielded its own sports teams. These were the arbitrary and capricious ways men got jobs on the waterfront. And, if someone had been identified as a union member, all the bribes he could put together wouldn't help. Any labor union that hoped to survive would have to stop the shape-up and prevent the I-I and the Big Five from being able to continue to use the blacklist against them.

In 1934 the West Coast dockworkers had won a closed shop hiring hall that put an end to that kind of management harassment, and the Hawaiian workers were determined to get the same protection from Inter-Island.

I-I went all out to sway public opinion against the union on this issue. They ran full page advertisements in the local papers on May 12th and 13th which were, later in the strike, followed by a front page editorial in the Advertiser on July 29th, each denouncing the “closed shop.”4

In March and April of 1938 the unions tried negotiating individually but the Inter-Island's position was unequivocal. Between April 19th and the 26th, the I-I negotiators rejected each union's proposals. Strike votes were taken, and it started to become clear that I-I was ready to take them on. From April to May, though the company was in sound economic condition, it actually laid off nearly 150 drydock workers, writing the union that:

The company sincerely hopes and will endeavor to avoid any reduction in personnel or rates but certainly cannot at this time entertain proposals which will add to the company's expenses without considering corresponding curtailment.5

In the face of this kind of harassment, the most incredible alliance was forged.

The IBU and the ILWU were CIO unions that only recently had been locked in an organizing battle for survival with the AFL affiliated HWWA. The three unions of the Metal Trades Council also belonged to the AFL, which the CIO unionists generally regarded as their bitter rival. But now they could see the times required unity in dealing with Inter-Island. The past had shown them all too many examples of strikes broken by the employers' ability to play one group off another. Though their unions were not divisible along racial lines, they knew the same "divide and rule" strategy would be used against them and doom their efforts as well.

On April 26th, the same day the I-I rejected the last of the union proposals, the Star-Bulletin reported:

A union spokesman said the ILWU and IBU . . . have agreed to present a 'united front' with the trades council, an AFL affiliate. No union, the spokesman said, will sign an agreement until each of the other two unions has reached an understanding with the company.

(page 2)

Of the 500 strikers that would go out together, about half were in the Metal Trades and half in the CIO affiliates. For their own survival, they both agreed to join in a "united front," whereby each would enjoy an equal voice in all their mutual deliberations throughout the dispute.

They spent another full month trying to negotiate a settlement, neither the unions nor the Inter-Island willing to give on these two issues. On May 26th at 4 p.m. members of the Honolulu based ILWU and IBU walked out, followed two days later by the MTC boilermakers, carpenters, machinists and electricians. They set up pickets in front of the company piers and drydocks as well as its offices.

For the first three weeks, the strikers were in good spirits and hopeful for a quick settlement. But I-I was not in this alone either. As only a strand in the Big Five web of corporate control, Inter-Island soon demonstrated to the unions that they were matched up against the massive resources of Hawaii's power elite.

With the assistance of Federal Mediator William Strentch, the parties did get back together, and the union submitted some counter-proposals on the hiring hall issue, but the company was adamant and rejected each new proposal as it had already rejected the entire concept.

After the third week, the company began to recruit non-union replacement workers, now determined to break the strike entirely. The mood of the strikers darkened and several sporadic episodes of violence occurred when the company announced the proposed sailing of the SS Hawaii manned by "scabs" and deserters, the worst involving the beating of two taxi drivers who, it was believed, were driving strikebreakers to the piers.

The press, ever eager to vilify the unions, seized the opportunity to unleash a torrent of bad publicity which had, at least, the one good effect of tightening the unions' discipline so as to stop any further incidents.6

But things were going from bad to worse for the strikers. Since the company had pulled together enough scabs to get a boat or two into service, the unions had decided to fall back somewhat and draw their line at the return of the two larger ships, the SS Waialeale and the SS Hualalai. The smaller ones, the SS Hawaii and the SS Humuula, came back on line with limited passenger and mail service and little union resistance.

By July, though, it was apparent that both of the unions' major issues were now lost. The unions may well have been ready to give up the strike altogether and return to work, but the I-I officials were then no longer content with merely winning the strike. They were committed to break the unions entirely. The chief bargaining issue of this last phase of the strike became whether or not striking union men would have the right to go back to work at all. As bad as things were going, the union men were renewed by that intransigence and again prepared to take their stand against the two big ships. For its part, Inter-Island on July 6th was ready to put the SS Waialeale in drydock preparatory to setting her back in regular service.

The Dynamite Plot

The day after the SS Waialeale went to the drydocks, the Honolulu police got a call of a plot to blow her up. A careful search did not reveal anything, but, a few days later, Charles B. Wilson, the disgruntled president of HWWA, informed Merton B. Carson, the acting manager of Inter-Island, of enough details to convince him there was a real possibility of danger. Carson called the police who immediately went to Wilson's home where they found 26 sticks of dynamite and four caps.7

It was Charles Wilson who had earlier been suspected by the IBU and ILWU of trying to organize a company union. Now he was mysteriously involved in a failed plot to dynamite the ship his CIO rivals and AFL brothers were striking. The end result, of course, served only to discredit the strikers, who had, since the taxi drivers incident, strenuously sought to control the growing anger and frustration of their members so as not to incite public opinion against their cause.

In a signed article in the union's newspaper, The Voice of Labor, entitled "WE ACCUSE!," (echoing Zola) the co-conspirators Wilson had named unanimously disavowed his entire scheme:

It doesn't make any sense that a "labor leader" who is furnishing "scabs" to the company and who has been aided and abetted by the company in organizing his union . . . would take into his confidence men he KNOWS distrust him, on matters of such a desperate nature.8

Conspiracy charges were brought against all of the men Wilson named, but Judge Harry Steiner dismissed the charges when the prosecution was unable to establish that any of them had been working with Wilson at all.9

In the end it appeared to be just another example of the framing of labor leaders on false charges. Reminiscent of the 1924 charges leveled against Pablo Manlapit, leader of the Filipino plantation strikes,10 the "dynamite plot," though later discredited, gave the press in the last weeks of the strike, ample occasion to lambaste the union and the cause of the strikers.

Notes:

1 The Reinecke Report, submitted as The Annual Report of the Social-Economic Plans Committee of the Hawaii Educational Association (Honolulu, 1939), p. 102.

2 Edward Beechert, Working in Hawaii: A Labor History (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985), p. 264; also in Reinecke Report, p. 115.

3 Colin MacKay as quoted in the Voice of Labor (May 12, 1938).

4 Star-Bulletin, May 12, 1938, p. 7; Advertiser May 13, 1938, page 7; Reinecke Report, pp. 109-110.

5 From a March 22nd letter I-I sent to the Metal Trades Council as quoted in The Voice of Labor (May 12, 1938), p. 4.

6 Reinecke Report, p. 130.

7 Ibid., p. 134.

8 Colin J. MacKay, Henry W. Keb and Edward Jennings of the Metal Trades Council, The Voice of Labor (July 21,1938), p. 4.

9 Reinecke Report, p. 135.

10 Eagen Report, p. 4608.

Part Three: Provocation

To fully understand the events that occurred on the morning of August 1st, 1938 on the Hilo wharves we must look back to what happened on the docks ten days earlier on Friday, July 22nd. After two months of little or no cargo service to Hilo or the other neighbor island ports, a great deal of pressure had built up on the company to bring her two main carriers, the Waialeale and the Huala-lai, back on line and restore full cargo services to the neighbor island merchants, whose businesses had, of course, been hard hit. The strike was clearly winding down. By mid-July the Honolulu unions had given up most of their major demands, but with the aid of its Big Five support, Inter-Island maintained its tough stance in the hope of breaking the unions completely. So on July 19th Inter-Island announced restoration of the Waialeale's cargo service to Kauai, Maui and Hilo.

What they didn't foresee was the sympathetic reaction of the Kauai and Hilo unionists. It must be emphasized that this was not a question of self-interest on the longshoremen's part. Inter-Island's cargo was traditionally loaded by its own crews, so the current strike was not one in which either the Kauai or the Hilo workers had a personal stake. The issue for them, quite simply, was the basic union principle that 'An Injury to One is an Injury to All." The Hilo Longshoremen had long before been recognized by C. Brewer, so the outcome of the Honolulu unions' action against Inter-Island would not profit them at all. But they looked upon the Honolulu workers as their union brothers and sisters and were, therefore, committed to help in whatever way they could.

Of the three Hilo piers in operation on the morning of July 22nd, two were being worked by Brewer longshoremen when the Waialeale was scheduled to come in. On pier 3 four gangs with nearly 50 men were working the Matson freighter Makua, while a similar number was working the Maliko on pier 1. They arranged with the Brewer agent, Mr. Armitage, to take a few hours off to peacefully demonstrate in support of the I-I strikers.

Coincidently, Hilo's chief law enforcement officer, Sheriff Henry K. Martin, was aboard the Waialeale on his return from Honolulu. He and a few other members of the Hilo Police Department had been there competing in a law enforcement officers' pistol tournament. 1

The acting Harbor Master, Captain Hasselgren, had heard of the union's plans to demonstrate, and decided to close the wharves under his emergency authority to head-off any difficulties. As the Attorney-General's report would later note, he did this under Section 11, item 4 of the Rules of the Board of Harbor Commissioners, which provides that "no person shall enter upon a wharf so closed without permission of the harbor master."2 At his request, therefore, Deputy Chief Pakele and Lieutenant Charles Warren with about eight men roped off the area going to pier 2 and prepared to deal with what they expected would be no more than a relatively small union demonstration. But by 9:10 when the ship came in, a large crowd of bystanders and members of the public had already gained access to the wharf and were gathering by the pier. As the longshoremen turned out for their demonstration, unarmed and mixed with a considerable group of people from the general public, including women and children, the unionists certainly assumed they should have the same right of access to the pier as the rest.

The whole crowd moved toward the ship, as the longshoremen proceeded to shout at the Waialeale crew in an effort to persuade them to quit "scabbing." No attempt was made to prevent any work from being done, but, as the newspapers noted, they did "boo and jeer" at the crew.

At this point, Lieutenant Charles Warren decided that the demonstration had gone too far. He went to his car and took out a tear gas bomb and, without authorization from the Sheriff or Deputy Sheriff who were both present, lobbed it into the middle of the crowd. 3

His bomb exploded in the face of an 11-year-old child, Onson Kim, who had to be rushed to the hospital. At that, someone yelled "bomb!" and the crowd began to stampede for safety, trampling three other small children. Ironically, the tear gas actually dispersed only the non-union by-standers and spectators. The longshoremen, for the most part, remained and were more adamant than before.

For the next hour or more, Harry Kamoku, as leader of the longshoremen, met with Thomas Strathairn, local manager of Inter-Island, to work out an agreement. Considering how close he thought the Honolulu strikers were to capitulation, Strathairn must, no doubt, have been amazed at the determination of the Hilo men, and decided it was little use running the risk of this kind of a demonstration as long as the strike was still on. Whatever I-I's strength might have been in Honolulu, Hilo was a different matter. According to James Mattoon of the Clerks' union, with whom Harry talked just after that meeting, he and Strathairn had come to a "gentlemen's agreement," whereby Strathairn had agreed that the Waialeale would not unload the balance of its Hilo cargo nor would the company return cargo service to Hilo, if the union would agree not to demonstrate against its mail and passenger service. After unloading only its mail, passengers, and some automobiles, the Waialeale left for Honolulu that night with 500 tons of cargo still on board.

Considerable debate would result over the exact nature of that Kamoku-Strathairn "gentlemen's agreement" over the next ten days. Strathairn would later state that he only told Kamoku there would be no more service to Hilo until he could be guaranteed adequate protection for the ship's crew and passengers.

There is no doubt that the union leadership all believed Strathairn had, in fact, promised to restrict cargo service to Hilo for the duration of the strike. According to the Associated Press announcement on the 22nd:

The Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co. announced today that its ships will avoid Hilo until there is assurance there will be no display of violence. The company made the announcement, following receipt of news of the Waialeale demonstration and cancelled the previously announced plan to return the Waialeale and Humuula to regular service. The Waialeale was to being [sic] regular service with her departure Monday at 5 p.m. for Hilo.4

It should be noted that in the subsequent investigation by Territorial Attorney General Hodgson, no violence was found to be attributable to any of the union demonstrators. The only violent actions taken, on both the 22nd and later on August 1st, were official police actions, notwithstanding the press insinuations to the contrary.5

In regard to the controversy between what would later be the different union and management interpretations of that Kamoku-Strathairn agreement on July 22nd, Hodgson concluded:

A bargain arrived at under such circumstances would of course have no binding effect. ... It seems very unlikely that a local agent with limited authority would, especially under such circumstances, give the assurance mentioned by the labor union people. . . . However, irrespective of what Mr. Strathairn's representations were, I believe that the labor union leaders conveyed their interpretation or mis-interpretation to the union memberships . . 6

It is curious, though, that he was able to come to such conclusions, when the transcript of his interrogation of Kamoku does not contain a single question relating to Kamoku's meeting with Stra-thairn. Hodgson's report has generally been praised and esteemed over the years as a most thorough and objective presentation of the incident. But it is only recently that the actual statements and other evidence Hodgson collected has been available for examination and analysis. This problem with the questioning of Kamoku is one of a number of flaws that, taken collectively, begin to cast doubt on the purity of Hodgson's inquiry. In this instance, for example, it seems just as reasonable to conclude there was a problem of communication between Strathairn's terminology and Kamoku's style, which was—after all—developed through his relationship with Brewer representatives, more accustomed to discussions with a union; or that Strathairn was simply too inexperienced to negotiate and did, in fact, mistakenly exceed his authority, then sought to retract or vitiate his former concessions. But, whatever the cause, it seems grossly unfair to conclude that Kamoku would just make up his version of that agreement, which is what Hodgson's remarks imply.

For a few days, though, immediately after the Waialeale returned to Honolulu, there was no dispute. Life went back to normal with Inter-Island preferring not to aggravate the tensions in Hilo. But then yet another party was to enter the contest and escalate the conflict once again. The Hilo Chamber of Commerce, as representative of the merchants, was no longer content to wait out the strike in Honolulu while their stocks and inventories dwindled to nothing. Their board met on July 26th and decided to call a special “public” meeting the following day in order to persuade Sheriff Martin and Strathairn of Inter-Island to agree to bring the Waialeale back.

On July 27th, even as the Chamber was holding its so-called “public meeting,”7] more trouble attended the Waialeale on Kaua'i. As she pulled into Nawiliwili, another crowd of about a 150 longshoremen turned out to jeer and boo the scab crew, even going so far as to cut the ship's lines to the pier.8

The day after the meeting was held in Hilo the headline of the Tribune Herald, whose General Manager, Kenneth Byerly, was himself a member of the chamber, proclaimed the chamber's position: “RESUMPTION OF I-I SERVICE IS SOUGHT.” The one hour meeting at the chamber's offices was called, as Hodgson correctly points out, “to give expressions to sentiment favorable to the resumption of Inter-Island sailings” and to put Sheriff Martin directly on the spot. Strathairn maintained that no service would be restored without guarantees of protection. The Sheriff, as might be expected, assured the merchants that he would protect the Waialeale if it were to come back. In answer to their concerns, the Sheriff read from a letter he had just sent to Stanley Kennedy, I-I President and General Manager in Honolulu:

I gave my guarantee and assurance to Mr. Strathairn that full protection will be afforded, and wish to five you that same assurance in order that normal commercial traffic can be resumed as soon as possible. Preparations are going ahead to enlist an adequate armed police, including reserves, in order to guarantee the forgoing protection.9

So it seems this meeting was held after decisions had already been made. Sheriff Martin had already been reached, and Inter-Island had apparently already made some kind of commitment to recommence its service. The Sheriff explained:

The police underestimated the waterfront situation in Hilo last Friday. Since the steamer had left Honolulu peacefully on the preceding day, the Hilo police did not anticipate any trouble here. We have no alibi to offer at this time for the unfortunate incident at the waterfront, but I can assure you that the next time a steamer comes here we will be fully prepared. We will have all passengers and freight unloaded under the protection of police guns.10

Also at the meeting was the longshoremen's leader Harry Kamoku. When he was asked to state his views, in the lion's den, Kamoku boldly reminded the chamber that despite their intention of holding a "public" meeting, what was convened was little more than a regular meeting of the chamber itself, and that they were receiving only one side of the issue. He described the plight of the I-I workers and admonished them, "We are fighting for our living while you businessmen are thinking only of your profits." He ended by warning them of the consequences of their position:

Our Union policy is 'No Violence.' We instruct our men not to go in for violence. The strike is now coming to a close and we don't want this body here to interfere in our fight. We want you to keep a hands-off policy. If not, we don't know what might happen.11

Though this admonition caused quite a stir, the chamber seemed to perceive it only as a threat that the union would resort to violence after all. They were convinced it was now properly a matter for the police, so they continued their pressure on the Sheriff.

The following day the paper announced the return of the Waialeale to Hilo, which was purportedly a decision made by General Manager Kennedy in view of the Sheriff's promised protection. Running next to that front page story was a companion announcement of Sheriff Martin's call for volunteers to act as special deputies when the ship comes in. “Those who register as volunteer special deputies will have their names on file at the police station and whenever they are needed they will be summoned by the sounding of the siren.”12

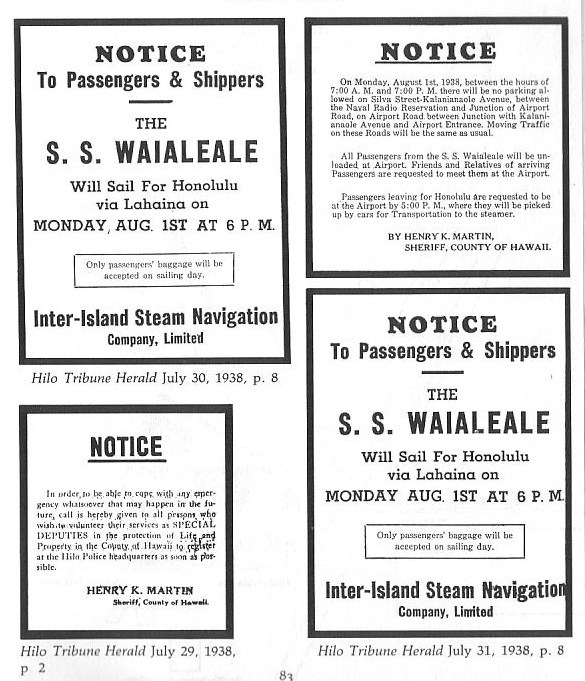

On July 30th and 31st, Inter-Island ran its usual notice in the Hilo Tribune Herald to shippers and passengers that the SS Waialeale would be sailing for Honolulu via Lahaina on Monday. And on the 31st, Sheriff Martin posted an additional notice in the paper forbidding parking on the streets by the wharves, and advising friends and relatives of passengers to await their passengers at the Airport.13 The notice, it should be remarked, did not close the wharf or forbid general access to the piers.

This raises a very important question that, to some extent, challenges the traditional interpretation of the incident. It has generally been accepted as a given that the union demonstrators were actually breaking the law by defying the Sheriff's orders to remain off the wharf. In the HEA report on the Inter-Island Strike, Reinecke noted:

Although normally the public has the right of access to Territorial piers, under section 11, Item 4 of the Rules of the Board of Harbor Commissioners . . . the demonstrators were deliberately committing a misdemeanor.14

Hodgson as well reports that the unionists knew they were not supposed to cross the Sheriff's line; knew there would be violence, but proceeded with the demonstration anyway:

On Friday and Saturday, July 29 and 30, the Hilo newspapers carried stories of the plans which the police were perfecting. It was stated that the plans involved the closing of Kalanianaole and Silva Streets at designated points. It was also stated that a picket fence would be erected at the place where Kuhio Road joins Kalanianaole Street, that a cordon of police officers would be stationed in the vicinity of the wharves, that those who had business on the wharves should secure passes from the police department . . . 15

Actually there were only two official police notices that appeared in the Hilo Tribune Herald on the 29th and 31st of July (see Appendix A). The first was a call for volunteer "Special Deputies" to register at the police department. The second was a notice that parking in the area would be prohibited and that passengers should be picked up at the Airport. There is no mention in these notices of the closure of the harbor or of the need to secure special passes from the police department. Even the news stories, which could hardly have been expected to serve as legal notification, contain no reference to Hasselgren's order or to the police passes Hodgson describes.

Interviews with several of the demonstrators, furthermore, indicated that they had received the opinions that their planned demonstration was legal, since the Sheriff did not have authority on territorial wharves, nor was the Harbor Master within his rights to restrict access of the wharves to some but not to others.16

Sheriff Martin, it would seem, had his own misgivings about his authority on the wharves and described in his statements to Hodgson how he sought advice from Gordon Scruton,17 Executive Secretary of the Hilo Chamber of Commerce, who advised the Sheriff to assure himself by consulting the County Attorney, W. Beers. Mr. Beers told the Sheriff to get a letter from acting Harbor Master Hasselgren making his request for police assistance a matter of record. Hasselgren quickly complied, though, as Hodgson notes,

At no time prior to delivery of this and at no time prior to the firing at the wharf on August 1 did Captain Hasselgren inform the Board of Harbor Commissioners of what transpired at the Chamber of Commerce meeting. . . . No request was made to the Territorial High Sheriff for assistance.18

While this short paragraph in Hodgson's report implies that Hasselgren may have exceeded his proper authority, and perhaps dragged Sheriff Martin along with him, Hodgson does not explore the issue, or comment on how this might have affected the propriety of the union's demonstration. His interviews did, however, reveal another feature of this question which was totally omitted from his report.

Though Hasselgren had not communicated with the Board of Harbor Commissioners, Louis S. Cain, Chairman of that Board, had been following the story through the press reports in the Honolulu papers. Ironically, Cain finally wired Hasselgren just as the police began shooting into the crowd. In a wire dated August 1st, 10:00 a.m., Cain gave Hasselgren the following instructions:

ADVERTISER STORY TODAY RE POLICING OF PIER NOTED STOP HARBOR BOARD IS NEUTRAL IN STRIKE STOP SO LONG AS PIER IS USED BY PUBLIC WITHOUT INTERFERING WITH PASSENGERS AND FREIGHT AND NO DISTURBANCE OR NUISANCE COMMITTED NO ACTION TO BE TAKEN BY HARBOR BOARD STOP IN CASE OF RIOT COMMA INTERFERENCE WITH USE OF DOCK COMMA OR PASSENGERS AND FREIGHT COMMA THEN ASSISTANCE OF SHERIFF IS TO BE REQUESTED IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO PRESERVE ORDER.19

It is not known exactly when he received this wire, whether it was later that day or there at Pier 2 as the shooting was already underway. Surely Hasselgren must have been alarmed and worried to find his supervisors so dramatically indisposed to the strategy he had adopted. In his report to Cain the following day, he had to justify his resort to the police by the following description of the demonstration:

The S.S. Waialeale arrived on August 1, 1938, at nine o'clock A. M., and a mob of approximately 600 men swarmed through the police lines to within fifty feet of the shed on Pier 2, where they finally stopped. The police tried to talk to them and to get them to move on but they insisted that they were going to rush the shed and board the vessel, which they finally attempted to do. The police opened fire on them injuring a number and restored order, and cleared the property of persons intending to create a disturbance. I in no way indicated to the police how they should maintain law and order or what steps they should take. You can see from this explanation of the situation that I have been carrying out the letter and spirit of your wire as well as the rules and regulations of the Board of Harbor Commissioners of the Territory of Hawai'i and at the same time have not taken sides in the labor dispute.20

That this is a deliberately distorted account of what actually happened August 1st shall be seen in the next chapter. If on the other hand this were generally what happened that day, it is likely that Sheriff Martin could have corroborated Hasselgren's depiction. Instead, in the last few lines of Hodgson's first interview of Sheriff Martin, the Sheriff expressed an entirely different assessment:

Q. Did the Harbor Master inform you that he had a wire from the Harbor Board that they were neutral and the crowd had a right to go on the pier so long as they would not destroy any property?

A. After this thing had happened. If that was given to me prior to that, we would have walked home.21

But why didn't the Attorney General cite any of this in his report? The omission of any reference to these findings casts serious aspersions on the reliability of Hodgson's report and suggests a deliberate intention to cover-up any Territorial culpability for the shootings.

Police Preparations

Notwithstanding the doubts Sheriff Martin was having about the jurisdiction of his authority, on the 28th of July he directed Deputy Sheriff Pakele (whose name in Hawaiian means 'escape') to work out a detailed strategy for the armed protection he had promised the Chamber. In an attempt to account for whatever the unions might be planning, Pakele's strategy called for a series of progressively more violent lines of defense that would begin at the highway entrance to the waterfront and end at the Waialeale where she would be tied up at pier 2. To avoid the problem they experienced on its last visit, when longshoremen simply walked over from the neighboring piers that were being worked, they arranged for the other two piers to be closed down also.

That same day, July 28th, patrolmen were taken to the National Guard firing range where they were shown the difference between the buckshot and bird shot cartridges they would be given. And they also demonstrated the difference between firing straight on at a target as opposed to shots ricocheted off the ground in front of a target as was recommended in riot situations.22

Pakele then delegated command of the different divisions. Deputy Chief Nahale would be in charge of the "club detail" of officers who would be responsible for the basic crowd control problems of an ordinary nature. Fire Department Chief Johnson Kahili would bring a firetruck and firehoses to shoot at the demonstrators as needed. And Lieutenant Charles Warren was assigned command of the tear gas and gun details.

Tear-Gas Warren

The choice of Lieutenant Warren for this crucial assignment is perplexing. Born in Honolulu as Charles Joseph Warren, Jr., he was a rather dark-skinned young Hawaiian whose father had been a servant to King Kalakaua, a member of the provisional troops that overthrew the monarchy, and a police captain before him. Charles, Jr. had served in the army during World War I and held rank in the Hilo unit of the National Guard. He had been off and on the police force at Hilo for about eight years since he joined in 1925.

Honolulu Star-Bulletin photo (September 23,

1938, p. 7), reprinted by permission |

From all the indications, he had the complete trust and confidence of the Sheriff, which is somewhat surprising considering his previous record. Just a week and a half earlier it had been Warren who had taken it upon himself, without the authorization of his superiors who were present, to blindly throw a tear gas bomb into a crowd composed as much of curious by-standers as of the longshoremen he was targeting. Flaunting "Tear-Gas Warren," as some were beginning to call him, before these same demonstrators with so much authority and command must certainly have been regarded by the unionists as a form of provocation. But Warren already had a reputation for impetuous and uncontrollable outbursts. Local attorney Martin Pence, who was at the time also a second judge of South Hilo district court, told Hodgson of a string of episodes in which Warren had been found guilty of police brutality:

He stated that Warren had arrested a boy and given him a brutal beating. The boy was later represented by Judge Metzger when Judge Metzger was practicing law and that boy had received a judgement in the sum of about $400.00 for the injuries he received.

Mr. Pence further stated that a client of his had been arrested by Warren and when the two of them arrived at the police station, Warren grabbed the man, twisted his arm and threw him against the wall, so that his face hit the wall, breaking his glasses and making a cut over one of his eyes. Later Warren paid for the glasses.

He further stated that at some boxing contest held in Hilo, a riot occurred while Warren was present and that Warren did nothing to stop the riot with the exception of setting up [sic] a tear gas bomb. Warren left the hall and after walking some distance to the street clubbed a person on the street . . ."23

Attorney General Hodgson scrupulously avoided drawing any official conclusions as to the guilt or responsibility of anyone involved in that day's events, and yet, beneath this veneer of objectivity, there are numerous instances revealing his personal support of the Sheriff. But Warren is another matter. Even Hodgson leaves us wondering how differently the day might have ended without Warren's prominent role.

Notes:

1 Hilo Tribune Herald (July 22,1938), p. 6.

2 J. V. Hodgson, "Report of the Attorney General in regard to the August 1 labor union demonstration at Hilo" (September 9,1938), p. 20.

3 "Statement of Charles J. Warren" (August 6th, 1938), pp. 6-8. Attorney General Pau Case Files #4791, Hawai'i State Archives.

4 Hilo Tribune Herald (July 22,1938), p. 1.

5 The press treatment referred to here is described and discussed in Part Five, pp. 52-54.

6 Hodgson Report, p. 25

7 As Harry Kamoku was to point out, the meeting was little more than a regular Chamber meeting, attended almost exclusively by those affected members of the Chamber of Commerce.

8 Reinecke Report (HEA), p. 138; and Star-Bulletin (July 27th, 1938).

9 Hilo Tribune Herald (July 28,1938), p. 1.

10 Ibid., pp. 1 and 7.

11 Ibid., p. 7.

12 Hilo Tribune Herald (July 29,1938), p. 1.

13 Hilo Tribune Herald (July 31,1938), p. 8.

14 Reinecke Report, p. 139n.

15 Hodgson Report, p. 36.

16 Joe Rocha recalls a meeting with Harry Kamoku and Territorial Deputy High Sheriff Walker who assured them that the County police did not have authority unless called in by the governor. See also Part Four, p. 30 for the advice given to the unionists by Judge Martin Pence.

17 A Canadian by birth, Scruton had come to Hawaii 15 years earlier to work as a reporter for the Advertiser. Most of the surviving unionists felt he was behind the Chamber's anti-union position. Later he would return to Honolulu as the personnel director for E. E. Black, then the head of the General Contractor's Association.

18 Hodgson Report, pp. 30-31.

19 Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

20 Letter from August Hasselgren to Louis S. Cain, Chairman, Board of Harbor Commissioners (August 2, 1938). Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

21 "Testimony of Henry K. Martin, Sheriff, County of Hawaii, taken by Mr. J. V. Hodgson, Attorney General, on Tuesday August 2, 1938, at 4:40 p.m. in room 212, Federal Building, Hilo, Hawaii," page 93. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

22 Hodgson Report, p. 31.

23 "Memorandum Re: Conversation with Martin Pence on August 3rd, 1938," pp. 96-97. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

PART FOUR:

THE HILO MASSACRE

In view of the elaborate police plans they heard were being drawn up and the daily stories in the Tribune Herald of the impending return to service of the S.S. Waialeale, the Hilo union members called for a joint meeting on Sunday July 31st at the Hilo Boathouse near Coconut Island to consider their plans. Present were about 250 members of the ILWU, Local 1-36—Long-shoremen and Warehousemen; ILWU, Local 1-36—Clerks; ILWU, Local 1-36—Ladies Auxiliary; United Laundry Workers, Local 832; The Quarryworkers International Union of North America, Branch 284; United Automobile Workers of America, Local 586; and a Teamsters local of the Hilo Transport Workers Association.

Harry Kamoku presided over the meeting at which there was considerable discussion over what they should do in response to the return of the Waialeale the next day. They were all told of Stra-thairn's "gentlemen's agreement" with Kamoku from the 22nd. Feeling was strong that some kind of a demonstration would be necessary.

David Furtado, a key organizer of the ILWU Clerk's unit, had picked up details of the police plans from a fellow National Guardsman and from his sister, a secretary in Doc Hill's office. He told them all how the police were planning to use tear gas, fire hoses, clubs and possibly riot guns if they attempted to get down by the pier.

Earlier that weekend Harry and several others had tried to talk to Gordon Scruton of the Chamber of Commerce. After calling the Sheriff for advice, Scruton would only tell them that his official statements would be published in paid advertisements in the paper; they should believe only what they read in those notices.1

Though this formal rebuff was duly recorded by Attorney General Hodgson, unaccountably, he later criticizes the unionists because “he labor union leaders made no such effort. No attempt was made to sit down and frankly discuss a situation which was rapidly becoming dangerous.”2

Also that weekend they paid a call on Judge Martin Pence for his opinion on their right to demonstrate on the wharf. Judge Pence, one of the island's handful of Democrats who had dared to cross swords with the Big Five by representing union clients, was willing to advise them manuahi (free-of-charge). As Hodgson records, he told them that the Harbor Master did have the right to close the Harbor, but he also told them they had as much right to be on the piers as anyone else so long as they conducted themselves in a peaceful manner.3

As they heard all these reports at their meeting on the 31st, consensus was quickly reached to proceed with a mass, joint demonstration. There was some concern about the women participating, in view of the possibility of a confrontation with armed police. But the women themselves insisted upon their right to attend. Almost two months earlier Theresa Hamauku of the Laundry Workers had written to the I-I strikers: "It takes lots of GUTS to face the whole world, and we know what it means to fight."4 She and her fellow workers had been through a rough organizing strike the year before, and neither they nor the Ladies Auxiliary were willing to back down on their pledges of support to the Inter-Island workers.

At this meeting they also decided that careful precautions must be taken to be sure that their demonstration would remain peaceful, regardless of whatever provocation they might encounter from the police. They were afraid that the police and the newspapers would seize upon the smallest excuse possible to lay the blame on them for any violence. They would meet any police force with "passive resistance."5

Here it must be noted how advanced sociologically their plans were. Of course Thoreau had conceived of the idea of civil disobedience nearly a hundred years before, and Gandhi had first developed the principle of satyagraha, non-violent civil disobedience as an organizational strategy during his civil rights campaign in South Africa around 1910. But conventional wisdom has normally credited Martin Luther King, Jr. with bringing Gandhi's tactic of passive resistance into modern use in America in the late 50's civil rights movement. And yet, here in the Territory of Hawaii, clearly, the Hilo unionists were using "passive resistance" per se in 1938.

To work out the details of the demonstration and assure there would be compliance with the consensus reached that Sunday, each of the seven unions, including the ladies auxiliary, delegated two representatives to sit on a special planning committee to consist of:

|

Harry Kamoku | ILWU Longshoremen |

|

Bernard Kamahele | ILWU Longshoremen |

|

Pascual Ruiz | ILWU Warehousemen |

|

Hideuchi Higuchi | ILWU Warehousemen |

|

Joseph Rocha | ILWU Clerks |

|

William Kaluhikaua | ILWU Clerks |

|

Anna Kamahele | Ladies Auxiliary |

|

Lee Kaneao | Ladies Auxiliary |

|

Basil Medeiros | Laundry Workers, Local 832 |

|

Norman Garcia | Laundry Workers, Local 832 |

|

Gilbert Perreira | Quarryworkers, No 284-22 |

|

Richard Kim | Quarryworkers, No 284-22 |

|

Leo Camara | Teamsters |

|

Ben Brown | Teamsters |

|

And, finally, as the group adjourned, they agreed to form up the next morning in front of Kealoha's store, the Block, at the corner of Kalanianaole and Silva streets. Those who were scheduled to work that day should seek time-off from their employers; everyone was to wear their regular work clothes.

The committee then met and developed the following specific rules which would be explained to everyone the next morning:

-

No violence of any kind;

- No weapons or tools that might be mistaken for weapons;

- No intoxicating liquor. Kealoha to close his bar and anyone smelling of alcohol shall be

sent home;

- No use of profane or obscene language permitted—only jeering at the Waialeale crew

allowed;

- Any police force was to be met with "passive resistance"— do not struggle with the

police, but just sit or lie down wherever you may be;

- Do not molest or harass the Waialeale passengers getting off the boat or leaving the

area with their baggage;

- Do not interfere with the loading or unloading of any of the cargo or mail;

- March peacefully down to Pier 2, eight abreast, men in front and women in back;

- If police throw tear-gas or use their "billies" (clubs) on the crowd, remain calm and lie

down in place until it's safe to get up;

- Once you get down by the Waialeale sit down throughout the demonstration, so that you

won't be accused of "rushing" the police. To get closer, the back row can move up in

front of the front row to gradually edge the crowd forward, non-threateningly.

- The demonstration would continue until noon at which time they would all be free to

return to their regular work or continue to demonstrate as it pleased them.

Regardless of these expressed goals and guidelines of the demonstration, which did not intend to prevent the unloading of the ship's passengers or cargo, Attorney General Hodgson's investigation continued to focus upon the exact location of the unions' ultimate destination, believing that,

if the object of the demonstration was to gain access to the area on the apron of the wharf between the warehouse and the S.S. Waialeale, the attaining of such object would necessarily result in the ship being unable to load or unload cargo which, in turn, would set at naught the Sheriff's promise of full protection upon the arrival of the ship.6

In his interrogations, therefore, much time was spent trying to establish a clear and premeditated union plan to attain that apron. But the many statements he elicited only pointed to the conclusion that there was no precise target in the committee's plan. Almost all of the union witnesses attested only to the idea that they were to get as close to the Waialeale as would permit their booing and jeering to be heard by the crew.

Nevertheless, Hodgson elected to quote in his official report the opinion of longshoreman Kenneth Moniz who was one of the only witnesses to describe the apron as their goal. Moniz, it must be noted, was not a member of the planning committee nor was he in any respect an organizer of the day's events. For Hodgson to make so much of Moniz' statement despite the weight of the vast majority of the other union witnesses on this question suggests the Attorney General was not being entirely unbiased in his analysis.

In any case, the effect of Hodgson's conclusions regarding the final goal of the demonstrators would lend support to Hasselgren's "rushing the shed" depiction, and, therefore, justify the Sheriff's resort to the use of deadly force.

The Night Before

Sunday night the police began to assemble at the wharf to be sure that the union men would not get there before they did. Officers from all over the island together with about a dozen deputized citizens were called in and assigned duty to one of the various sections, which besides the club, tear gas and gun details also included a detective squad which would work the boat and passengers; a team of unarmed "specials," who were friendly with many of the unionists and, therefore, assigned to talk them out of whatever they were planning; and a photographic detail to obtain pictures that might possibly be used for future evidence.

In all, Hodgson tabulated the total police detail to deal with the demonstration at 68 officers and special volunteer deputies. However, it is possible by cross referencing testimonies to actually identify by name as many as 74 men (see Appendix C). Under the over-all command of Deputy Chief Peter Pakele, they set up two police lines to stop the progress of the marchers. The first was marked off by a yellow line drawn on the road together with a partial picket fence at the top of Kuhio road where it joins the highway, directly across from Kealoha's store, "the block" (see Appendix B). The second line, "the dead line" as Warren called it,7] was drawn in yellow about 350 feet further down Kuhio. Still quite some ways from the pier, this line was understood by Warren to represent the point beyond which his forces were to be unleashed to drive the unions back.

At his command was a small arsenal of 52 riot guns with bayonets (originally purchased in 1924 on the occasion of the Filipino plantation strike led by Manlapit), 4 Thompson sub-machine guns, tear gas grenades, and an adequate supply of ammunition including both buckshot and birdshot cartridges for the riot guns.

And finally, the Hilo Fire Department was assigned to dispatch a pumping truck and enough firemen as might be needed to repulse the marchers with hoses.

Outside of the official police force that was assembling, the Inter-Island Navigation Company had also prepared a squad of its own 'specials.' Under the command of Port Captain Herbert T. Martin (not related to Sheriff Martin), aboard the Waialeale was a team of eight or more thugs that I-I used like a SWAT team to deal with labor disturbances. Inter-Island was concerned about a repeat of the Nawiliwili incident in which the hawsers from the ship were cut by the unionists. Martin revealed to Hodgson that,

I flew to Kauai to break that mess, to straighten that mess out . . . Yes, I flew to Kauai and got that mess straightened out there, and they had no more trouble over there after that.8

Indeed his job was to "break" the strike and the union. His Honolulu squadmembers were not carried as crew on the ship's logs. Their job was apparently to stop any attempt of the unions to cut the Waialeale's lines and to marshal the rest of the crew as necessary to make sure the cargo was properly unloaded at Hilo. They were armed with 50 hickory trundle sticks, a dozen flare or "Very Guns," several of the ship's hoses deployed for use to repel boarders, and—though it was never proven and adamantly denied by Martin— various Hilo witnesses, including police, observed them with police badges and hand guns. Nevertheless, as Hodgson notes: "The police conducted no investigation, either at the time or afterwards to determine whether there were armed men on the ship."9

August 1st: The Demonstration Begins

The Waialeale was expected around 9:00 a.m. But some of the longshoremen started to gather at "the block" as early as 6:30 that day. Harry Kamoku was watching from early in the morning and finally spotted her off Pepeekeo. The word went out, and by 8:30 a.m. the majority of the unionists began to arrive, walking down from each different direction.

One of the most difficult questions, which even Hodgson was unable to solve precisely, was the exact number of demonstrators that actually were there. Witnesses estimated the crowd anywhere from 80 to 800, with the newspapers reports running around 500 to 600. One difficulty in getting a reliable figure arises out of the fact that a considerable number of those present were just curious by-standers not related to the union.

Hodgson was inclined to settle on an estimate between 250 and 300. No one seems to have used the many photographs taken that day to actually count heads. Careful study of enlargements of two such photos, one taken of the demonstrators as they reassembled after the tear gassing and hosing, and the other taken of the crowd shortly before the firing revealed a considerably smaller number. In both cases the crowd seemed to be undiluted by onlookers. Separating out the figures established as police, in the first photo there were 169 visible, and in the second about 158 could be seen, with a few more believed to have been outside the camera range. This latter day photographic analysis is certainly subject to some error, but is likely an indication that even the formerly conservative estimate of 250 was somewhat exaggerated. There is, after all, a natural tendency to exaggerate an opposing force, and it must have been difficult at many points to tell the difference between demonstrators and other members of the general public just there to watch the event as it unfolded. It may well be, therefore, that either the demonstration had thinned by that later stage, or that Hodgson's estimate of the size of the crowd, based entirely on the various statements he collected, was itself exaggerated.

It seems most plausible to estimate that the demonstration that day may well have started with about 200 or more union members but was thinned considerably after the first tear gassing and was carried out in the main by about 175 members of Hilo's local unions, including about thirty women.10 Of this number it is possible to identify by name through the various records just over a hundred of them (see Appendix D). When the number of shot and wounded later is matched up against this reassessment, it means that a significant percentage of the crowd was, in fact, to fall before police fire.

As the crowd began to collect in front of Kealoha's store between 8:30 and 9:00, the Waialeale could be seen coming in to her berth. At 9:00 a.m. she tied up and started to unload, so a small delegation of the unionists went over to the police line to talk to Sheriff Martin. Two photographs, later identified as "Camera Craft pictures #5 and #6," show this conference (see page below). The unions were represented by Harry Kamoku, James Mattoon, Leo Camara, Bernard and Anna Kamahele, Lydia Papalima Lui, and a few others. The Sheriff was backed up by Wallace Naope, one of the "special" deputies, and Deputy Sheriff Pakele. As Sheriff Martin tells it, this is what was said:

They told me they wanted to have a demonstration and they wanted to go down to the boat and see who was on that boat. I told them I am sorry the men in charge of the dock has asked me to keep everybody out, not only you people but others and not to allow anyone except those who had actual business as I said.

So they said, "How about us going down in here"? They knew all about this country. They said the wharf line was about here where the railroad. . . I said, "That is impossible. You will be interfering with the passengers. . . . You will be interfering with the freight and passengers coming out. This is a big street. You can march up and down and stage all you want as long as you don't interfere with the people traveling."11

They also asked the Sheriff to bring Strathairn out to discuss their agreement from July 22nd, but the Sheriff told them he couldn't do that. Harry and the others then went back to the crowd to let them know what they had been told. James Mattoon was appointed to speak to them. He got up on a little hill across from the store and made a speech that the police regarded as inflammatory. According to the statement he made to the Attorney General, this is what he said:

I told them that at the previous arrival of the Waialeale the agreement Strathairn made with us was a gentlemen's agreement, and that he did not live up to his word, and had gone right ahead and did what he pleased, and that the sheriff was there on a request of the big shots from Honolulu, and that is why the sheriff was there, and I said "Now it is up to the union members". I said "Now it is up to you".

Q. What did the crowd say? What did the unionists say when you said "Now it is up to

you"?

A. They clapped and before I knew it they were marching on.12

Without any specific order, the crowd formed up and began to march down singing as they went, "The more we get together, together, together; The more we get together, the better we'll be!" While in the back the women were singing, "Hail, hail the gang's all here."

With Harry Kamoku, his cousin Isaac "Chicken" Kamoku, David "Red" Kupukaa, and Raymond Namau in the front line, they brushed past the Sheriff and his Deputy whose feeble shouts of "Stop, stop" were barely heard even by his own men.

Down Kuhio Road they went, quickly approaching Warren's "dead line." About 40 feet away from that line on either side, Sergeants Walter Victor and Vernon Stevens with officers Callahan, Kuroyama and Otani were ready with tear gas grenades. As the first of them reached that second line, each of the officers threw two or three grenades into the crowd until about a dozen had been set off.

The crowd broke with a few running off to the right toward the Pacific Guano and Fertilizer buildings, but with most running to the left into the pu hala trees and then on to the park further down the road. As Anna Kamahele recalled:

We were moving down singing, "Hail, hail, the gang's all here" and the first thing you know the first group was about to turn at the Inter-Island wharf, and we were by the small little house, the railroad house, and we saw smoke coming out, and everybody stopped right there, and somebody yelled "Tear gas". It came like fireworks, and I did not know where it was coming from and I ran to the puahala [sic] trees and some laid flat on the ground.13

Some of the braver ones, especially those who had experience in the local unit of the National Guard, had come with their leather work gloves and so were able to pick up the grenades and threw them back at the police or off to the side. One of the officers who tried to throw a grenade back again burned his hand before he realized how hot the grenades become after exploding. In a few minutes, as the air settled the demonstrators walked down to the little park with the coconut trees bringing the balance of the crowd closer to pier 2 than the police had ever calculated.

In the meantime the police were getting the fire truck ready to pump sea water through the hoses to push them all back up to Kalanianaole. But when they tried to operate the hoses, some of the firemen had been blinded by the gas, so they could run the hoses at only about 85 pounds of pressure, less than half of normal. The firechief's heart didn't seem to be in it anyway. His statement to the Attorney General later would reveal incidentally that Harry and Chicken Kamoku were his nephews, and that he had not even brought enough men to man the four hoses they brought if they were used at full pressure. He had left half of his men back at the station to protect the rest of Hilo.14 In any event, the hoses (not running at full pressure) were totally ineffective, so after a few feeble attempts to spray the demonstrators which succeeded only in clearing the tear gas out of the air and cooling off the gravel area in front of the pier, that part of the plan was given up.

For about five minutes the crowd was in confusion and disarray, yet, it should be noted, the police made no attempt to arrest anyone then or at any time during the whole course of the incident. Whether the police were still unconvinced as to their legal authority to make such arrests or whether they were reluctant on account of the close inter-relationships of so many of the union members with police and fire officials present, is only possible to conjecture. But Sheriff Martin had apparently taken the position that he would try to defuse the situation with Hawaiian-style "Ho'omali-mali." 15 Unfortunately, this did not seem to be the position Strathairn had adopted, and the Sheriff was unable to bring the two parties together as had happened on the 22nd.

Before long the crowd had recovered sufficiently to reassemble on the gravel area between the park and the pier (see Appendix B). They stood there while Harry Kamoku and the others went forward to request again a chance to speak with Strathairn. At this point Sheriff Martin actually tried to pull a trick on the union leaders to assert a clearer and more absolute authority over them. He asked Kamoku, Mattoon and the others to raise their right hands while he started to deputize them, but they all dropped their hands and walked away. With that failed ploy, the sheriff returned to the pier shed. Five or ten minutes passed and the unionists began to sit down in place to wait it out. They played card games like 'donkey' and sang songs hoping that the Sheriff would be able to leverage Strathairn out for a parley. Special officer Moody Keliihoomalu, who knew most of the unionists, recalled:

A. They asked us to go ahead and get the committee, and we [he and the Sheriff] said all

right. In fact I suggested that we have the committee from the ship agree about it, so we

came in to see Mr. Strathairn the manager and told him the boys demand to see the

delegates on the ship, by the name of Thompson. He did not say anything. The

attorney was standing there.

Q. Who is the attorney?

A. Wendell Carlsmith. We asked and he said no.

Q. Who said that?

A. Carlsmith.

Q. What did you do then?

A. I pleaded. ... I talked to him for quite a while before he agreed. He said "I will try". He

went out to see Captain Martin of Honolulu, the harbormaster, the marshall.

Q. So that Carlsmith went to talk to the Inter-Island port captain Martin?

A. Yes.

Q. He said that nobody from the ship can come off.16

Passengers were loaded into automobiles and driven off to the airport, yet no word came from Strathairn. At last the union formed up again and prepared to move forward, but Deputy Sheriff Pakele warned them that his men were prepared to use force if necessary to stop them from going any farther. At this, the demonstrators seemed to disperse, but were actually breaking up into three groups. Most of them collected around the fire truck over by the sea wall directly in front of the Waialeale; a second group remained on the pavement on Kuhio Road; and a third smaller group spread out into a thin line on the loose gravel area in front of the pier 2 and pier 3 shed.

The police likewise fanned out to match the rough semi-circle that the crowd had now formed. It is interesting to note that in organized demonstrations such as these, the police and the press often seek to characterize the crowd as a "mob" or "riot" while at the same time complaining of the "military precision" of its actions. It's hard to understand how it can be both, but this is exactly what was to occur in the police and press reports of the Hilo unionists. The Sheriff was obviously caught off guard by the division of the crowd into different sections. Particularly since their first impression was that the whole assembly was now dispersing as they had hoped.

Sitting down and remaining, by all accounts, quiet and peaceful, the demonstrators remained true to their plans. They were not being violent or abusive. Their language was neither obscene, profane or threatening bodily harm. To get closer to the ship, those in the back walked up and sat in front of those sitting in the front, gradually edging the demonstration close enough to be heard. They occasionally booed at the Waialeale's "scab" crew, or at police Lieutenant Charles Warren or Sheriff Martin for their roles in upholding the interests of the company's owners instead of his own people, but most of the witnesses agreed there were no especially provocative or threatening words or deeds from the demonstrators.

As this was happening, the eight-man gang from Honolulu under Captain H. T. Martin's command came out and took up positions on the apron of the wharf directly behind a white picket fence set up to separate the demonstrators from the ship's hawsers. Feeling confident and obviously unthreatened by the demonstrators, they leaned over the fence and glared at the crowd of unionists. Sheriff Martin saw them and was told by Chief of Detectives Richardson that the crewmen of the Waialeale had been overheard talking about the arms they were carrying to deal with the situation. When the Sheriff went over there to talk to Port Captain Martin, he was warned, "If you can't handle them, I will!" This threat was to weigh heavily on the Sheriffs mind, and yet he never checked that rumor out, nor did he regard their presence as legally improper, as Hodgson's interrogation revealed:

Q. Will you repeat what he [Port Captain Martin] said?

A. He came out there and he was practically yelling at me. He said "That mob is getting too

close and if you can't handle them, I will take things over and act".

Q. What did you say to him?

A. I told him to go back in the shed.

Q. Why didn't you arrest him?

A. For the same reason. I saw no reason for arresting him at that time.

Q. You saw no reason for arresting those men at any time before the firing?

A. No, I did not, Sir.

Q. When you say you saw no reason for arresting any of those men before the firing, what

do you mean by that?

A. I presumed they were special officers who came with the ship. That is the impression I

received, and many others had that idea. As a matter of fact I saw two with badges just

sticking out of their pockets.17

From everything the Sheriff has said, it is clear that his decision to authorize the firing on the crowd was based on his understanding that the ship's crew was, indeed, heavily armed and on the verge of independent action. Two days after the incident, the Sheriff went on the local radio station and explained his actions to the people of Hilo:

When the Waialeale came to port she had aboard 84 men, heavily armed. : In addition, there were arms intended to repel shore mob attacks. These men were powerful fellows and were prepared to fight. They would have remained on the ship and at start of any of 500 oncomers attempting to go aboard, they would have been hit on the head and dropped into the bay.

I knew that any such clash would result in the death of a large number of local boys.18

The Sheriff seemed to have believed he had something of a Hob-son's choice before him, so he decided that if anyone were going to shoot into the crowd it would be his men with bird shot instead of the full scale weaponry he imagined to be aboard the ship. He ordered his men to change their ammunition from the larger buckshot to the less harmful birdshot, and set out to disperse the crowd once and for all. Unfortunately, not many of the officers assigned to the gun squad ever heard that order; they were spread out in a semi-circle trying to move the demonstrators back.

Theresa Hamauku, nineteen years old at the time and one of the leaders of the Laundry Workers Union, recalled the way the policemen tried to frighten them:

The only time they talked to the police officers was when he said he had orders to shoot, and there was a fellow who belongs to Keaukaha and he said, "If you shot me and I died who is going to take care of my wife" and the police officer turned around and said, "I will give her to the Filipinos" and he said if you die or get hurt would you like me to give your wife to the Filipinos?" and he said "No". That was officer Kahale.

Q. Was he laughing when he said that?

A. Yes.10

In fact, these threats had little effect. Theresa herself, after two officers physically dragged her to the back of the crowd, just picked herself up and marched right back to the front where she was, to the applause of her brother unionists.

There are many that have laid the blame for the carnage on Lieutenant Charles Warren. The support for this is the evidence that Lieutenant Warren was the first to come bounding out of the pier shed to where Kai Uratani and Red Kupukaa were sitting in the third section of the crowd, stretched out in front of pier 2 and 3. Smarting from the jeering and taunts directed at him through the morning, Warren told the men, "OK, You've been calling for Charlie Warren to come out. Well, here I am. And now I'm giving you three minutes to get out." With that he stepped up to Kai Uratani, slapped him on the side of his face with the side of his bayonet blade.

Uratani lying on the ground began to get up and Warren then lunged his bayonet into the side of Uratani's back. He described to Hodgson:

Kai Uratani |

Q. Now, as I understand it, you were in a leaning posture, reclining on the ground on your

elbow, and Warren came up, and after he pricked you and slapped you with the

bayonet on the face, you started to get up. Had you got on to your feet when he

stabbed you with the bayonet?

A. No, I was sitting down.

Q. What direction was your back to officer Warren?

A. My back was turned to him.

Q. Your back was turned to officer Warren?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you see him move the gun and stab you with the bayonet?

A. I did not see.

Q. You felt something under your arm?

A. Yes, but before I felt something under my arm I felt a poke.

Q. You felt a poke?

A. Yes. I did not know I was stabbed. After I felt something running I looked at my hand

and I see blood.

Q. You saw blood. And at that time you had your back toward officer Warren, and you

were looking toward the crowd of people?

A. Yes.

Q. After Warren did that to you did he do anything else?

A. He went for Tony Moniz.

Q. What did he do to Tony Moniz?

A. Tony Moniz was here on this side and I saw him just giving a poke with the bayonet at

Tony Moniz' trousers.

Q. You saw him give a poke with the bayonet at Tony Moniz' trousers?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you see the bayonet go into Tony Moniz?

A. I saw the bayonet go into Tony Moniz'trousers.

Q. What did Tony Moniz do?

A. He just slipped off.20

Longshoreman Red Kupuka'a, one of the few unionists in the demonstration who had a record of minor arrests with the police, shouted out "Hey, You can't do that!" and Warren stepped over to him, swung the butt end of his rifle up into Kupukaa's jaw and laid him out. Two officers picked him up and moved him back a few feet, then stepped back as Warren took his first shot into the crowd, followed almost immediately by the volleys of the rest of the gun squad until the shooting subsided entirely after about five minutes. It was just about 10:20 a.m.

In the affray at least 16 rounds of ammunition were fired: seven birdshot—as Martin had ordered—and nine buckshot. When it was over, fifty people, including two women and two children, had been shot; at least one man bayoneted and another's jaw nearly broken for speaking up for his fallen brother.

The savagery of the final police attack that day is not easy to explain especially in view of Sheriff Martin's earlier conciliatory efforts. Perhaps the growing police frustration as they tried to cope with the unions' determined but non-violent demonstration, when it was at last released, created a frenzy. Longshoremen Robert Napeahi's testimony to Hodgson tells of just such a melee:

Q. Do you know who fired in your direction?

A. No. At that time a woman fell, shot; it was near where I was standing. She called and

told me she was shot. I heard the second shooting, rapid fire, and I took cover over her.

I covered her. She is my sister-in-law.

Q. You got in front of her so she would not get shot again?

A. Yes.

Q. And you got shot in the side?

A. Yes. After that I lift her and I asked her how she feels and I carried her past the fire

engine and Harry Kamoku and my brother gave a hand. While I was moving away,

naturally when you pick up a wounded woman you can't move fast, Kahale was there,

poking a club and he said "Move, keep moving"; oh, I would not say it was Kahale that

did the poking. There was a couple more cops there, but there was somebody behind

me poking me with a club, saying "Move, keep moving" and some of them said "Let

them have it".

Q. So that you got in front of your sister-in-law, and the policeman, so that she would not

get shot again?

A. Yes. She fell down and called me and told me she got shot. Shooting again came twice,

so far as I know, and instead of standing there I just lie myself right on top of her so that

she would not get shot again.

Q. Was that when you got shot?

A. Yes, that's when I got shot.

Q. Where were you shot?

A. In the skull here.

Q. Now your sister-in-law, what is her name?

A. Helen Napeahi

Q. Where was she shot?

A. In the back. In the afternoon I saw her and asked her where she was shot and she said

practically all in the back.21

Two days after the shooting Harry Kamoku tried to tell the story over the phone to Edward Herman in Honolulu between half choked sobs:

They shot us down like a herd of sheep. We didn't have a chance. The firing kept up for about five minutes. They just kept on pumping buckshot and bullets into our bodies. They shot men in the back as they ran. They shot men who were trying to help wounded comrades and women. They ripped their bodies with bayonets. It was just plain slaughter, Brother Berman. 22

Some have said this was all due to Lieutenant Charles Warren, who was personally to blame for losing his temper and starting the shooting on his own authority in the same way he caused the tear gassing of the crowd on the 22nd, ten days earlier. Sheriff Martin, then, under this interpretation, is believed to have nobly taken the blame for the rash behavior of his Lieutenant, by insisting that he did give the order to open fire, though he never authorized bayonets or the use of the buckshot.

There are, however, some major problems with such a reading of the Sheriff's role. A considerable amount of testimony of union as well as by-stander and police witnesses supports the allegation —denied by Martin—that several minutes before Warren's attack, the by-standers and some of the personal relatives of police officers among the unionists were, in fact, warned to move away or clear the area since the shooting was about to start. Anne Kaluhikaua, for instance, was called aside by her uncle, Officer Kekela, and removed to the rear of the crowd only moments before the shooting.23

Other witnesses also testify that 'special' officer Seiji Matsu and Deputy Sheriff Pakele went around to the near-by sampans in the harbor and other on-lookers by pier 1, warning them to seek cover or clear the area as the police were about to use force to disperse the crowd. If the shooting had not been premeditated, but simply the result of Warren's outburst; and, if Sheriff Martin were just accepting blame, then how is it Pakele, Kekela and Matsu were in positions to know of the impending danger? And why should Martin so vehemently deny what so many other unbiased witnesses can establish as evidence, that the shooting was by plan and not by accident?

Sheriff Martin's testimony is, in fact, riddled with the strangest inconsistencies and denials that seriously impugn his credibility. He insisted that he gave a full and complete order and warning to the unionists as they began to cross the first yellow line, but even other police witnesses present were unable to support that. He denied that 'special' officer Seiji Matsu was assigned to take photographs of the crowd, but the testimony of other 'specials' contradict his denial, and other photographs show Matsu doing just that. And, most unbelievably, at several points, when being questioned by the Attorney General about the guns and ammunition, the Sheriff claims, "As a matter of fact I don't know much about arms and firearms. I have never carried a gun myself."24 And yet, just three weeks before, the Hilo Tribune Herald had run his picture holding a pistol with the caption "The Shooting Sheriff," as he returned from a pistol shooting competition in Honolulu.

Hilo Tribune Herald photo (July 22, 1938, p. 6) Hilo Tribune Herald photo (July 22, 1938, p. 6)

courtesy of Hawaii Tribune Herald |

Most distressing of all, is that Attorney General Hodgson did not seem in the least troubled with the Sheriff's testimony. Rather, he proclaimed in the prefatory remarks of his report that he believed "neither the labor union members as a class nor the police or fire department members as classes attempted deception."25

Notes

1 Hodgson Report, pp. 36-37.

2 Ibid., pp. 45-46.

3 "Memorandum Re: Conversation with Martin Pence on August 3rd, 1938," p. 96. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

4 Theresa Hamauku's letter to the Joint ILWU-IBU Strike Committee (June 6,1938) as published in the Voice of Labor (June 9,1938), p. 3.

5 Hodgson Report, p. 39.

6 Ibid., p. 44.

7 "Statement of Charles J. Warren" (August 6, 1938), p. 23. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

8 "Statement of Captain Herbert T. Martin" (August 15, 1938), p. 93. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

9 Hodgson Report, p. 53.

10 The women were from the union representing the workers at White Star Laundry and from the Ladies' Auxiliary not from Kress Store, as has often been reported.

11 "Testimony of Henry K. Martin, Sheriff, County of Hawaii" (August 2, 1938) p. 72. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

12 "Statement of James K. Mattoon" (August 12, 1938), pp. 25-26. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.

13 "Statement of Mrs. Anna Kamahele" (August 16th, 1938), p. 6. Attorney General Pau Case Files, Hawai'i State Archives.