Weathering the storms

For 50 years, meteorology has been a small department with broad vision

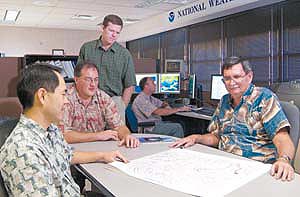

Located at Mānoa, the National Weather Service provides study opportunities for students and employment for graduates including, from left, Kevin Kodama (’MS 95), Andy Nash (MS ’92, BS ’90), doctoral candidate Matthew Sitkowski (MS ’07), Bob Burke (BS ’91) and Tim Craig (MS ’72, BS ’70)

In 1839 David Malo, a member of King Kamehameha’s court, completed his book Hawaiian Antiquities, which includes Hawaiian descriptions of weather phenomenon. The following year, Navy Lt. Charles Wilkes recorded some of the islands’ first instrument weather observations atop Mauna Loa.

Plantation and territorial U.S. Weather Bureau offices kept rainfall and temperature records for more than a century, but it wasn’t until World War II that the majority of scientists realized tropical weather doesn’t play by the mid-latitude rules laid out in the relatively new science of meteorology.

While the military began basic meteorology work at Wheeler Field, agricultural interests tested new methods for seeding clouds to produce rain. "Although no meaningful weather modification technique ensued, the body of work done included significant elements," observes Thomas Schroeder, director of UH’s Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research and a former meteorology department chair.

The Weather Service was also involved in early research on rainfall, interaction of trade winds and sea breezes, evolution of Kona storms and the link between major volcanic eruptions and large haze episodes, says Schroeder, who has compiled a history of meteorology in Hawaiʻi.

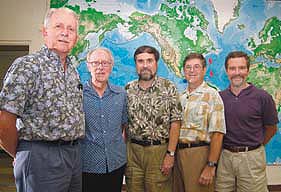

All the department’s chairs past and present gathered for an anniversary conference; from left, Thomas Schroeder, Colin Ramage, Kevin Hamilton, Duane Stevens and Gary Barnes

Even as these efforts waned, a 1956 Air Force contract with the University of Hawaiʻi for research on Pacific typhoons provided for a training program and meteorological library—the genesis of Mānoa’s Department of Meteorology. Deputy-Director Colin Ramage of the Royal Observatory in Hong Kong was recruited to lead the program.

Within a decade, six-week training courses for government meteorologists developed into a strong BS program, the department graduated its first doctoral candidates and moved into the new Hawaiʻi Institute of Geophysics quarters, and UH joined the consortium managing the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

UH faculty participated in an international observation campaign, which fortuitously coincided with a major El Niño event, in 1957. They analyzed the first weather satellite images in 1960, revealing a high frequency in East Pacific tropical cyclones, producing comprehensive atlases of cloudiness and proving the new technology’s usefulness in estimating rainfall and gauging storm intensity. Ramage directed meteorological programs on a subsequent international oceanographic expedition of the Indian Ocean that produced a seminal textbook on monsoon meteorology.

In the late ’60s, interest turned to cloud physics and warm cloud precipitation. An observatory was established on the mauka edge of the UH Hilo campus in the country’s rainiest city. A career of fundamental monsoon research earned UH’s Takio Murakami the Meteorological Society of Japan’s highest honor. Mānoa scientists also directed national research related to the 1972–73 El Niño that decimated Peru’s anchovy fishery and its economy.

In 1977 UH and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration created the Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research to pursue areas of mutual interest, including climate and tropical meteorology. Warming U.S. relations with China led to an early and lasting relationship—UH’s first Chinese-funded graduate student enrolled in meteorology and China regularly supplies visiting faculty.

External acclaim doesn’t ensure local popularity. The department sidestepped campus turmoil over the Vietnam War when faculty member Maj. James Sadler told critics of military funded research that better weather forecasts save lives on both sides of a conflict. (His work on the tropical upper tropospheric trough remains important in understanding trade wind weather and plotting optimal aircraft routes.) During financial hard times, lawmakers pressed UH to cut programs with low faculty-student ratios, but the state was quick to seek university expertise on wind and solar studies when the 1973 oil embargo spurred interest in alternative energy.

During the 1980s, Schroeder described the conditions producing violent weather systems and worked with geographer Thomas Giambelluca to produce rain maps that remain the standard 20 years later. University reorganization placed the department under the new School of Ocean and Earth Sciences and Technology in 1989, with an energetic new chair in Duane Stevens; Dean C. Barry Raleigh declared climate research a major SOEST focus.

The National Weather Service moved to campus in 1995, creating synergetic opportunities for research and student experience. "We’re probably the most integrated of the 13 co-located weather service offices," says Jim Weyman, Honolulu meteorologist-in-charge. "Our doors are open to students and faculty. We employ a number of students." Fifteen UH graduates have gone to work for the weather service since the move, four of them in Honolulu. "UH efforts to improve forecast models for Hawaiʻi help us meet our mission to protect and save human lives and property," Weyman adds.

In another UH-based collaboration, Mānoa, U.S. and Japanese agencies created the International Pacific Research Center to focus on climate variability and global change. Among those hired was meteorology alumnus Tim Li, who studies ocean-atmosphere dynamics, cyclogenesis and forecasting, and stratospheric dynamics expert Kevin Hamilton, who also serves as department chair. Gary Barnes and Bin Wang revitalized hurricane research, arriving shortly before Hurricane ʻIniki created media demand for guest experts and trained weathercasters. Wang studies the interaction of storm winds and Earth’s rotation to understand a cyclone’s motion while Barnes investigates how air-sea interactions influence intensity change, a fundamental forecast problem. Yuqing Wang focuses on what happens at the storm’s vortex.

Meanwhile, interdisciplinary work on El Niño continues on the meteorology side. Fei-Fei Jin’s comprehensive model of El Niño formation accounts for differences in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Professor Yi-Leng Chen explores the pre-monsoon Mei-yu front, barrier jets and sea breeze circulation of southern China and Taiwan as well as circulation and rain formation on the Big Island. Steven Businger investigates dispersion of volcanic smog from Kīlauea and weather and turbulence forecasting pertinent to astronomers on Mauna Kea and Haleakalā.

There may be plenty that scientists still don’t know about the weather, but the forecast is getting better.