A Part of Kalaupapa

UH alumni and faculty reflect on a special community

The Kalaupapa peninsula

Millions of years ago a small shield volcano on the north side of Molokaʻi erupted and formed the Kalaupapa peninsula, a windblown spit separated from topside Molokaʻi by the highest sea cliffs in the world. The pali stretches thousands of feet above the flat leaf of land, where archaeological evidence suggests Hawaiian people have lived for at least a thousand years. In 1866, new, mostly unwilling settlers arrived, victims of a malady that disproportionately afflicted Hawaiians and terrified the non-indigenous population: leprosy (also called Hansen’s disease).

The hardships of the community’s early days have been told and retold. Before the state officially abolished isolation laws in 1969, more than 8,000 people had been separated from families, tracked by bounty hunters, prodded by doctors, shunned by neighbors, denied their children, subjected to substandard care and condemned to exile. The Kalaupapa Peninsula is full of graves, and the histories are often heartbreaking. But that 10-square-mile triangle of land also became a place that many love—a place of beauty, comfort, refuge and livelihood.

The University of Hawaiʻi is a minor player in the history of Kalaupapa. Graduate student Alice Augusta Ball (MS ’15) was the first chemist to find an extract to treat Hansen’s disease; future UH President Arthur Dean’s therapy using her chaulmoogra oil extract was used around the world with mixed success until the 1940s brought an effective cure. Diagnosed with Hansen's disease two weeks after graduation, Shizuo Harada (BA ’25) ran the Kalaupapa general store and organized athletic leagues.

Decades later, UH medical faculty participated on the committee urging an end to isolation laws. Professor Terence Knapp originated a one-man drama that popularized Kalaupapa priest Father Damien on stage and national TV, and student activist Bernard Punikai'a, who had had Hansen’s disease, protested for patients’ rights. Now UH medical staff and historians are part of the story, as is a former patient, storyteller Makia Malo who, after 25 years of confinement at Kalaupapa, overcame great odds to become a UH student.

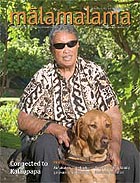

The storyteller

For Malo, coming to Kalaupapa in 1947 was not a choice, but leaving to live in Honolulu and, in 1972, to attend UH Mānoa was. Both required great bravery. As a young child, Malo was taken from his family and sent to Kalaupapa, where three siblings were already incarcerated. Like many patients, he found a measure of happiness even as Hansen’s disease racked his body, claiming feeling, fingers and even his eyesight before it was arrested. In Honolulu, a physical therapist encouraged him to enter a writing contest, which he won. He then channeled his enormous creative and intellectual energy toward the university.

"I wasn’t following in anyone’s shoes, so it was hard. There were no stepping stones to follow," he recalls. At age 37, he had a clear idea of what he wanted to study—voice, Hawaiian language and writing. He worked closely with staff at Mānoa’s KOKUA Program to navigate the campus and explore new intellectual worlds. They recorded his books on tape while he recorded his lectures; he recorded notes for both onto another set of tapes and listened to hours of audio, effectively memorizing lessons for each class.

In addition to Hawaiian, Malo studied German, and then Spanish, where he hit a barrier of ignorance on the first day of class. "I asked a question and there was no sound. 'Hello,’ I said. 'Excuse me?’ No sound. Later I heard from this girl who was helping me that the teacher was just staring at me. Her eyes were so big, staring at me, and she wouldn’t answer. I knew that she was scared because I had had leprosy. I dropped the course. I no can handle that kine wasting my time. I had too much to do. But I was sorry I missed the opportunity to learn Spanish."

Dorming at Gateway, he was fully immersed in the community of students. He sang and played in concerts at Orvis Auditorium, served on the Campus Center Board Activities Council and acted in a play. He became well-known both for the distinct figure he cut and the magnetic personality that anchors his career as a storyteller. He earned a BA in Hawaiian studies in 1979 and a teaching certificate two years later.

"What kept me going was that I realized none of the guys that I grew up with had the privilege of doing what I was doing," he says. "They all died, a lot of the kids, so I’m pulling them with me. Tony, Charley, Donkey, oh a whole bunch of them. These were the guys I kept in my heart, in my mind when it got really, really rough. They never had the chance so I just pushed on for all of us."

Malo has done storytelling and Hawaiian chant in Hawaiʻi, the mainland, New Zealand and Canada and made special appearances at the United Nations Headquarters, Spain’s World Expo and Scotland’s Edinburgh Festival. Now 72, he serves on the state Developmental Disabilities Council. He shares his stories and music on two soon to be released self-produced CDs, Tales of a Hawaiian Boyhood, The Honolulu Years and The Kalaupapa Years, an important source of livelihood. (Call 808 949-4999 for information.)

Despite their modest means, the Malos endowed a scholarship at the Hawaiʻi Community Foundation. Awarded yearly to a Native Hawaiian student of law, it is dedicated to "all the people who never had the opportunity to live beyond the boundaries of Kalaupapa."

His manager and wife of 17 years, Ann, works tirelessly to educate people about the hurtful and dehumanizing impact of using the term "leper," which reduces individuals to a disease they once had. "What we ask instead is to use the word "person" before the name of any disease," she says.

The visiting doctors

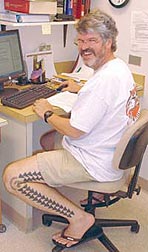

Mānoa physician Kalani Brady cares for a population subject to the afflictions of aging

With wire-rimmed glasses, kind eyes and a neatly trimmed salt-and-pepper beard, Kalani Brady looks every bit the typical physician. Meeting him off-duty, when he’s wearing shorts, slippahs and a t-shirt, reveals a bit more: a Hawaiian tattoo running the length of his left leg that includes a taro plant at his knee. Brady warns against romanticizing the role he and other doctors play in the Kalaupapa community. Yet he speaks with conviction when he says, "We have a very sacred calling here, we’re very privileged to be in this position."

Brady and fellow John A. Burns School of Medicine physicians Martina Kamaka and Peter Donnelley provide care for the fewer than 30 remaining patients, all of whom have chosen to spend their senior years at Kalaupapa. They are likely to be the last doctors of Kalaupapa, says Brady. "We are grateful to have been chosen and trusted by the patients to be their caregivers. Because we are all young enough, we intend to be here as long as we’re needed."

A large percentage, though by no means all, of the individuals sent to Kalaupapa were people of Polynesian descent who found family separation particularly trying. The people providing medical services overwhelmingly were western. "I don’t think that we could’ve expected those walking before us to discover the therapeutics any sooner, because that had to take its own time. But cultural insensitivity has been responsible for a lot of pain, a lot of cultural displacement of Native Hawaiians," Brady says. "If you read the accounts there were probably doctors, like today, who shouldn’t have been practicing in a cross-cultural context."

Brady is at the Kalaupapa clinic one day a week; the others visit twice a month. Drug therapy has arrested Hansen’s disease in all their patients, but residents are afflicted with other diseases common with age. "High blood pressure, diabetes, cholesterol problems, heart disease, chronic kidney disease—three of our patients are on dialysis here in Kalaupapa," Brady says. Services at the clinic are limited, and some residents have to go to Honolulu for care. Today state laws guarantee both care and dignity for the remaining residents.

The medical school’s Imi Hoʻola program helps bridge the gap between local patients and their doctors. Since 1972, Imi Hoʻola has worked with promising yet socially, educationally or economically disadvantaged students (including many of Pacific island descent). They complete an intensive year of class work that includes a spring retreat in Kalaupapa and make a commitment to serve in areas of need in Hawaiʻi and the Pacific. "It is important that these young, aspiring medical students gain an understanding of the history of leprosy in Hawaiʻi and the impact it has had on people’s lives over the years," says Director Nanette Judd, who for 25 years has lead the retreat.

The resident caregivers

Alumni nurses Kathleen Aiwohi, Julie Sigler and Earleen Rapoza staff the community clinic

Clinic staff members are full-time residents of Kalaupapa. Three of the seven nurses are graduates of UH nursing programs—Kathleen "Tita" Aiwohi (’87 Mānoa) and Earleen Rapoza (’86 Kauaʻi), hired in the past year, and Julie Sigler (’82 Kauaʻi), who has lived and worked at Kalaupapa for 13 years. Former hairdresser Rapoza says the training she received at Kauaʻi CC prepared her for service in Kalaupapa.

"When I graduated, it was basic nursing care that kept people from getting pneumonia. We learned head-to-toe assessment to analyze what’s going on and use that here all the time." Kalaupapa nurses have to be independent and confident. There is no air ambulance at night, no reinforcements when an emergency happens.

The nurses also accept isolation, expensive travel and rules against bringing young children into the community, as well as the emotional burden of watching patients they love pass away. Many find great personal fulfillment in service. "What we’re doing means so much, it’s like a whole different aspect of nursing," explains Aiwohi, who spent 20 years providing trauma and critical care services, most recently at Hilo Medical Center. "I tell the patients all the time, ʻI’m honored to be here.’ These people deserve the best, they have been through so much and treated so poorly in the past." Unfortunately, ignorance persists outside the community. "People ask, ʻAren’t you afraid to work down there?’" she says with a sigh. "I found serenity, I found peace and happiness, I found my calling."

"We’re not only nurses, we’re neighbors, we’re friends. We go to parties with residents, sit next to them at the funerals, hold their hands when loved ones die," Sigler adds. She recalls riding past the cemetery with a patient. "He said, ʻThat was my neighbor, and that was the man I played baseball with, and that was my first wife, and that was my cousin.’ Each one of the graves has a meaning to them, it’s a person, it’s a loss."

The historians

Hilo professors Charles Langlas and Sonia Juvik record the latest oral histories

Kalaupapa also draws historians. Hilo Assistant Professor Kerri Inglis studies 19th century attempts to treat leprosy. Mānoa Associate Professor Noenoe Silva and graduate assistant Pualeilani Fernandez have collected letters and stories of patients from 19th century Hawaiian language newspapers.

Oral historians preserve the past as told by the people who lived it. The residents, who have endured unwanted examination for much of their lives, sometimes find that telling their stories in their own words balances heavily dramatized works.

The 1979 collection of largely anonymous histories Maʻi Hoʻokaʻawale: The Separating Sickness by Mānoa’s Ted Gugelyk and Milton Bloombaum laid the groundwork. Mānoa alumna Anwei Law (MPH ’82) is coordinator of the ILA Global Project on the History of Leprosy’s oral history component. She is drawing on letters and more than 200 hours of interviews over the past 25 years for a book to be published by UH Press.

To create a complete picture of the community over time, the National Park Service commissioned and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs funded follow-up work by a UH Hilo team. Anthropologist Charles Langlas, geographer Sonia Juvik and anthropology alumna Kaʻohulani McGuire (’96 Hilo) are collecting stories of as many remaining patients as possible. "We want to describe what people’s lives were like at Kalaupapa, how they ended up there and why they decided to stay after they were not required by law to do so," Langlas says. "We’re looking at both what you might call the tragedies of their lives and the good things as well—they married, worked and played, just like everyone else."

The team includes anybody who’s willing and able, but Langlas suspects some histories will never be heard outside the peninsula. "We’re interviewing probably 12. There are a few who refused. One felt like she had told her story and she was tired of telling; one guy is very shy; a few people have talked to us a bit, but haven’t wanted to be recorded and have their story become a part of what we publish."

Those who do participate contribute not only to an important part of Hawaiʻi’s history, but to family histories as well. People might discover they had relatives at Kalaupapa, Punikaiʻa once reflected. "If they feel at all the same way that we do, they will be proud that their family was part of the ʻaina, part of the soul of this land."