A Conservationist’s Palette

Interview with melissa chimera by Pat Matsueda

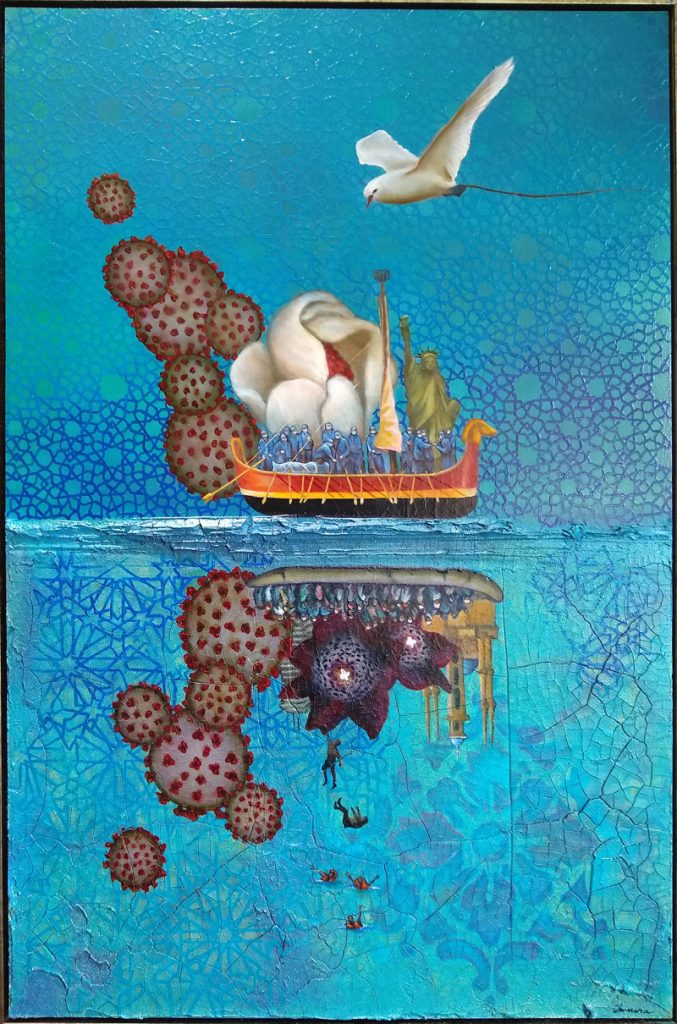

Melissa Chimera is a conservationist and Honolulu native of Lebanese and Filipino ancestry. Her work investigates species extinction, globalization and human migration and has been exhibited worldwide, with solo shows such as Migrant at the Honolulu Museum of Art and Agents of Change at the Hui No‘eau Visual Arts Center, Maui. Her most recent project as artist and curator is The Far Shore: Navigating Homelands for the Arab American National Museum. The exhibition of contemporary art and poetry concerns a highly politicized issue—Arab immigration to America—viewed through the lens of the personal and familial. She is the recipient of the Catherine E. B. Cox Award and has been named as a finalist for the 2019 Lange-Taylor Prize, Duke University Documentary Studies. She keeps a studio on Hawai‘i Island, where she lives with her husband and son.

Pat Matsueda, founder of Vice-Versa, conducted this interview.

VV The Anthropocene Epoch has made us acutely aware of the interconnections among things. You explore that in your art. Can you tell us which connections you are most passionate about?

MC My background in ecology informs the work. I am interested in that uniquely human space that either accepts or rejects others and the world around us. That uncomfortable territory we encounter every day and in every interaction. What prevents us from bonding with things outside of our tribe? For millennia, our species depended on group conformity and resource extraction to survive. Now these adaptive behaviors no longer serve us in the global context. How do we harness the natural affinity, the solidarity we feel for one another during natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina or the COVID-19 pandemic and apply that to everyday life? Social inequality and the climate crisis are fundamentally manifestations of our disconnect with each other and the natural world. Despite our extraordinary affluence and connectivity relative to the span of human history, we are lonelier than ever. We need a new paradigm.

VV There is a strong educational component in your art, as is true of much of the art being produced today. Do you think this is the result of knowing how much we can influence the future with our choices?

MC To be honest, I don’t know to what degree we as artists influence anything. Art making is so individual. For me, my subject matter, endangered species and immigrants are an extension of my values, the way I live my life. I try to not confuse making and viewing art with the hard work of activism in social, economic or environmental justice. That said, prevailing narratives of humans as a selfish, inherently violent species haven’t served us. And it isn’t supported in the science either. We need alternatives to the proposition that we are either headed towards extinction or another planet once we are done with this one. Rebecca Solnit has written on how we overlook positive changes right in front of us. Extraordinary paradigm shifts have come suddenly–like with civil rights movement, gay marriage, the youth climate strike. This isn’t to say these changes aren’t years in the making. But on the other hand, look at how quickly the world shut down in solidarity to prevent the spread of COVID-19. If you had told me that we would do this collectively as a global community six months ago, I wouldn’t have believed it.

VV You play with scale in your art: large things are small, and small things are large. This produces a dynamic kind of equality in your work. Would you like to say something about that?

MC Scale is intriguing to me–maps, the microbiome and macro universe. The African American painter Mark Bradford said that his maps depicting communities of color are themselves abstractions. At the citywide view, people are statistics, like the number of homeless in Los Angeles, or blue versus red voting counties. Maps at that scale don’t capture individual lives. Similarly, it seems we are all caught up in a quest for some kind of objective reality that doesn’t really exist. Or rather, the reality we live in exists beside other realities. Varying scale in my work attempts to upend the idea of a singular, verifiable perspective. Is our prevailing human-centered perspective the only reality? What is real; me as an ecosystem for billions of microbes or as a speck of carbon and water among the stars, an artist-mom-wife, or all of them at once?

VV You’ve lived in different biomes: volcanic, rainforest, near the shore. What have you observed about weather, temperature, plant-life changes in these places? How do these affect your perceptions of the ways the world is changing?

MC I have spent decades helping to protect Hawaiian ecosystems you mention. And it is depressing to be quite honest. We live in one of the most ecologically and species-rich archipelagos on Earth. So much is fast disappearing. The intersection of fires, floods, drought, mass migration is accelerating. We may appreciate sunsets in a hundred years, but what about the living things? It is interesting to me that thirty years ago, we were once so excited for the 21st century. Talk of the future permeated film, novels, television. Now, we speak of the next century with dread if we mention it at all. And yet, making art is about as hopeful an endeavor as planting a tree. I don’t mean hope as a passive wish, but rather as Krista Tippett describes it—hope as an active muscle. If we don’t take small steps alongside bigger ones, then what is the alternative?