Wonder Drug or Latest Fad?

Not all noni’s purported benefits have traditional origins

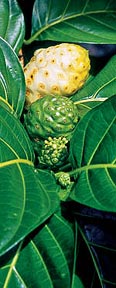

Bumbo, cheesefruit, lada, nho, bankoro, hog apple, mouse’s pineapple or limburger tree. With so many names, perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that products from Morinda citrifolia, aka noni, represent a $3 billion industry.

Noni photo courtesy of the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources

At about $1 per fluid ounce retail, noni has one of the world’s highest profit-margins for juice beverages, according to Scot Nelson, a plant pathologist in the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. Nelson has developed the definitive noni website.

Odorous when ripe and bitter tasting when aged, noni has a reputation as a cure-all for ailments ranging from arthritis to ulcers. Scientists are looking at compounds that may have potential benefits, but experts say the fruit is unlikely to live up to all the claims.

A member of the coffee family, noni is a small evergreen tree or shrub that bears bumpy, fleshy yellowish-white fruit. The fruit is turned into juice and sold in its pure form or as juice concentrates, beverages or powders. Dehydrated pulp is made into fruit leather and dried leaves are crushed for medicinal and cosmetic use. Oil is derived from pressed seeds for use in shampoos and other modern topical applications.

The market for noni products is worldwide, with largest distribution in North America, Mexico, Asia and Australia.

Traditional uses

The plant may have colonized Pacific islands naturally, but many believe it was brought to Hawaiʻi by the Polynesians. They used the noni bark and root to make yellow and red dyes.

As botanists, the voyagers knew what they were doing—noni thrives in a wide range of precipitation levels, temperatures and soil conditions. It survives in arid regions, lava fields and brackish tide pools. It regenerates after fire or severe pruning and can flower year-round.

The Polynesians generally limited noni’s use to topical applications, according to Mānoa ethnobotanist Will McClatchey. The elder healers he’s interviewed in Hawaiʻi and other Pacific regions describe using heated leaves as bandages, placing chopped leaves within wounds and applying green fruit in external remedies. Non-healers used crushed or sliced fruit as poultices for infections or skin ailments.

Noni juice has grown in popularity over the past 20 years, fueled by claims that it can treat cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes, AIDS and depression.

"The popularity of M citrifolia fruit in modern Hawaiʻi seems to hinge on a combination of its tradition of use among Polynesians, development and distribution of modern products and a mixture of factual and fanciful information provided directly by manufacturers and indirectly by academic researchers," McClatchey writes in Integrative Cancer Therapies.

Unsubstantiated claims

McClatchey groups noni health claims in three categories. One relates to traditional Polynesian uses. Others he traces to an undocumented 1985 botanical garden newsletter article that extols an unsubstantiated alkaloid dubbed zeronine. Third are miscellaneous vague claims.

Noni products provided by ʻUmeke Market

"As with other panaceas, M citrifolia is being marketed as ʻhope in a bottle’ which will ʻnaturally’ treat illnesses that are otherwise out of the control of the average person," concludes McClatchey.

Noni juice is high in vitamin C, and scientists have isolated potentially promising compounds, including immune-boosting and anti-bacterial polysaccharides, anti-inflammatory scopoletin and antiseptic anthraquinones.

Scientific studies

Some studies have begun to test specific claims. A. Y. Hirazumi studied anticancer and immunotherapy potential of the fruit for her UH doctoral dissertation. She determined that noni juice could stimulate an immune response in cells and exhibited promising anticarcinogenic properties. Mānoa Professor of Pharmacology Eiichi Furusawa demonstrated antitumor activity of noni juice in mice.

The Cancer Research Center of Hawaiʻi continues the work with funding from the National Institutes of Health and Hawaiʻi Community Foundation. Researchers must first determine safe and tolerable dosages of noni capsules. Measurement of biologically active chemicals in the urine helps determine a minimum level to maintain presence in the bloodstream while interviews gauge the maximum dose that can be accommodated without adverse effects.

Later, efficacy studies will compare noni against a placebo to determine actual benefits.

It’s only anecdotal evidence so far, but lead researcher Brian Issell says some of the 50 patients participating in the dosage study report reduced pain.

Bottom line? Drink noni if you like—Nelson’s website will even tell you how to make your own juice—but be cautious about unsubstantiated claims.

Blueberry could be healthy newcomer

Blueberry fruit

Blueberries, nature’s little sack of vision protecting, cholesterol lowering antioxidants, could become a high-value niche crop for Hawaiʻi. Mānoa researchers and USDA colleagues are testing the crop’s viability at the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources’ Mealani Research Station in Waimea.

Six heat-tolerant cultivars of the North American native shrub are being tested because they don’t require a Mainland chill to flower.

The researchers will follow the plants for several years, but preliminary observations are promising. Four cultivars have produced good yields of high quality fruit. Emerald and Misty had the largest berries, Sharpblue the sweetest.

Visit CTAHR publications to download the blueberry publication under "Fruits and Nuts."

Breadfruit is still a healthy staple

Hawaiians once cultivated breadfruit, or ʻulu, in large groves.

The wood was used for surfboards and the bark for kapa and bandages. The sap served as a salve, calk and glue for catching birds. The pale pulpy fruit was used to chum for fish and feed pigs.

And baked, boiled, worked into a poi or cooked as a pudding, ʻulu was a dietary staple that rivals taro in nutritional value.

Breadfruit’s popularity as a food declined by the 1920s, but Mānoa food scientists Alan Titchenal and Alvin Huang aren’t ready to abandon the plant. "This beautiful, productive tree has an ongoing role to play in the Hawaiian lifestyle," they write in Hawaiian Breadfruit: Ethnobotany, Nutrition and Human Ecology.

Go to CTAHR publications and click on "for-sale publications" at left or call (808)956-7036 to order the book.