Imagine what life could be like on Mars. What would you need to survive in an extreme space environment? High school students in Hawaiʻi, through a partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and ʻIolani School’s ʻĀina Informatics Network (AIN), are getting a hands-on science education, while incorporating Hawaiian cultural values, to figure out what life may be like on other planets, such as Mars.

UH Mānoa Research Affiliate and alumna, Professor Rebecca Prescott, UH Mānoa School of Life Sciences Professor Stuart Donachie, and other national and international researchers, helped develop a joint research-education program, by providing AIN with bacteria and bacterial DNA from Hawaiian lava caves and other sites, and developing teacher-training workshops and place-based lessons.

Preparing for Moon, Mars missions

prioriisuperbiae for their school motto.

Sites such as Hawaiʻi lava caves are important in astrobiology, a field of research that looks to extreme environments on Earth to determine how microbes can survive in similar environments on other planets. Hawaiʻi’s active Kīlauea volcano, lava tubes and volcanic soils are similar to those found on Mars, and have the potential to help in NASA’s Artemis missions to the Moon in 2026, and Mars in the 2030s.

Additional bacteria came from hypersaline ponds in the Bahamas, and a species used in experiments aboard the International Space Station (ISS) via the University of Edinburgh. Full genomes help researchers understand the data from their ISS experiments, and provide a link for students in Hawaiʻi to be involved in ISS research, and with the European Space Agency.

AIN educators, with the help of UH Mānoa researchers and non-profit Kauluakalana, bring an ethical and place-based science curriculum that examines the cultural importance of these locations to high school classrooms, connecting the biological and functional diversity of these bacteria to places in the Hawaiian cultural landscape.

“This program has truly been a collaborative, multi-institutional effort, with no one party able to complete as much as we have together,” said Prescott, who is also an assistant professor at the University of Mississippi. “We found that a combination of teacher training workshops, sustained and financially supported education programs like AIN, and long-term relationships with a variety of federal agencies and research institutions, is required to effectively blend research and education goals. We will need more of this in the future to solve real-world problems, like the challenges of creating permanent and sustainable settlements on Mars.”

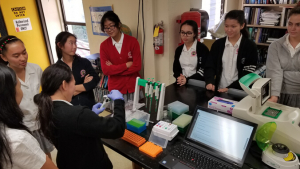

UH Mānoa and AIN students’ sequencing and understanding of the genomes was possible through use of EDGE Bioinformatics, a web-based bioinformatics tool created by collaborators at Los Alamos National Laboratory. ʻIolani School’s AIN “mobile lab” includes high tech devices and computer support, such as ULANA, a user-friendly tool created by ʻIolani School’s Ethan Hill, a graduate of UH Mānoa, which allows students to work with bacterial genomes and gain experience in genomics and bioinformatics.

Students and community members also named three of the new bacteria species, all of which were cultivated in 2017 by two undergraduates in a UH Mānoa Research Experience for Undergraduates program, funded by the National Science Foundation.

Students at St. Andrew’s Priory proposed the name Bradyrhizobium prioriisuperbiae after their school motto. This bacterium is also being studied to understand how it breaks down basalt and meteorites. Kauluakalana proposed the name Brenneria uluponensis, after the Native Hawaiian historical and agricultural restoration site, Ulupō, where it was discovered. Hawaiʻi Baptist Academy students proposed the name Paraflavitalea speifideiaquila, also after their school motto.

The findings have been published in Astrobiology.

This joint research-education program is supported by the National Science Foundation, NASA, U.S. Department of Energy and more.

The UH Mānoa School of Life Sciences is housed in the College of Natural Sciences.