The Hawaiian language is more than just words—it is an experience, it is food, it is music, it is dance, it is a culture and way of life.

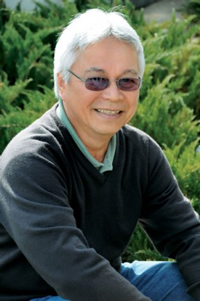

“Food, music, and dance all come with the language—they can’t be separated,” says Larry Kimura, associate professor of Hawaiian language and Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo.

Kimura shared his views at this year’s He ʻŌlelo Ola Hilo Field Study event. The two-day conference on February 28 and March 1 was buzzing with people from around the world who are working toward revitalizing indigenous languages. All were engaged in celebrating the growth of the Hawaiian language in particular—a model to the world—and discussing the next steps in furthering Hawaiian language revitalization and spreading it across all of Hawaiʻi.

He ʻŌlelo Ola Hilo

He ʻŌlelo Ola Hilo is a field study hosted each year at UH Hilo for an international group of indigenous language specialists. It allows attendees to experience firsthand the efforts being made to revitalize the Hawaiian language using Hawaiian as the medium of formal education from the infant toddler level all the way to college degrees.

The event featured record attendance and the majority were native peoples or those working with endangered native languages from Okinawa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Alaska, Minnesota, New Mexico and the U.S.

Field study participants visited ʻAha Pūnana Leo, kindergarten–high school Hawaiian immersion program Nāwahīokalaniʻōpuʻu, UH Hilo’s Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani College of Hawaiian Language and Hawaiian immersion teacher licensing program Kahuawaiola.

“Our K–20 program is in our language but it’s not only about the language itself—it’s about education through our language,” says Kimura.

The first full fledged Hawaiian immersion school started in 1985. According to Kimura, the third generation of Hawaiian speakers are beginning to attend these schools—theses students are born and raised with Hawaiian language in their homes through at least age three to four, which makes them the new native speakers.

“Linguists have determined that it takes at least three generations to reestablish a language and bring it back to life,” Kimura explains. In order to keep the language alive, he says, it must be included in the home not only in the school.

Kimura says there is unprecedented efforts at preserving native plant and animal species and the preservation of the language should be handled with the same urgency and energy.

“We don’t want to reestablish our language just to have it die because we are not cultivating the environment for it to flourish,” he says.

For more about expanding immersion language education, read the full article at UH Hilo Stories.

—A UH Hilo Stories article written by Anne Rivera, a public information intern in the Office of the Chancellor, and photos by Zoe Coffman