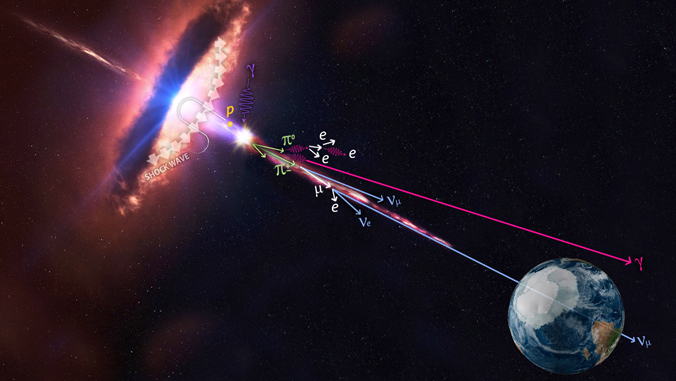

Astronomers and physicists around the world, including at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Institute for Astronomy, have begun to unravel a long-standing cosmic mystery. Using a vast array of telescopes in space and on Earth, they have identified a source of cosmic rays: highly energetic particles that continuously rain down on Earth from space.

In a paper published this week in the journal Science, scientists have, for the first time, provided evidence for a known blazar, designated TXS 0506+056, as a source of high-energy neutrinos.

At 8:54 p.m. on September 22, 2017, the National Science Foundation-supported IceCube neutrino observatory at the South Pole detected a high energy neutrino from a direction near the constellation Orion. Just 44 seconds later an alert went out to the entire astronomical community.

The All Sky Automated Survey for SuperNovae team (ASAS–SN), an international collaboration headquartered at Ohio State University, immediately jumped into action. ASAS–SN uses a network of 20 small, 14-centimeter telescopes in Hawaiʻi, Texas, Chile and South Africa to scan the visible sky every 20 hours looking for very bright supernovae. It is the only all-sky, real-time variability survey in existence.

“When ASAS–SN receives an alert from IceCube, we automatically find the first available ASAS–SN telescope that can see that area of the sky and observe it as quickly as possible,” said Benjamin Shappee, an astronomer at the University of Hawaiʻi Institute for Astronomy and an ASAS–SN core member.

On September 23, only 13 hours after the initial alert, the recently commissioned ASAS–SN unit at McDonald Observatory in Texas mapped the sky in the area of the neutrino detection. Those observations and the more than 800 images of the same part of the sky taken since October 2012 by the first ASAS–SN unit, located on Haleakalā, showed that TXS 0506+056 had entered its highest state since 2012.

About 20 observatories on Earth and in space have also participated in this discovery. This includes the 8.4-meter Subaru Telescope on Maunakea, which was used to observe the host galaxy of TXS 0506+056 in an attempt to measure its distance, and thus determine the intrinsic luminosity, or energy output, of the blazar. These observations are difficult, because the blazar jet is much brighter than the host galaxy. Disentangling the jet and the host requires the largest telescopes in the world, like those on Maunakea.

“This discovery demonstrates how the many different telescopes and detectors around and above the world can come together to tell us something amazing about our Universe. This also emphasizes the critical role that telescopes in Hawaiʻi play in that community,” said Shappee.

Go the the Institute for Astronomy website for more about the discovery.