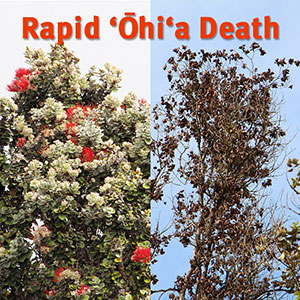

Researchers in Hawaiʻi, working with national and international specialists, have published a paper providing new insight into the origin and development of the tree disease called Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death. Scientists at the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and the University of Hawaiʻi worked with colleagues at the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, and Iowa State to describe two new species of plant pathogenic fungi known to cause Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death. Initially noticed by landowners in Puna in 2010, Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death spread quickly across tens of thousands of acres on Hawaiʻi Island, killing hundreds of thousands of native ʻōhiʻa trees (Metrosideros polymorpha) in a short time. A plant pathology team led by Lisa Keith at the ARS laboratory in Hilo went to work collecting and analyzing samples of dead and dying ʻōhiʻa.

In 2014, tests confirmed that the culprit was a fungus, tentatively identified as Ceratocystis fimbriata. Around the world, Ceratocystis fungi are known to attack many plants, including coffee, cacao and mango. Some varieties of the fungus are genetically different from the others, so that plants tend to have their own specialized attacker. The species of Ceratocystis that attacks cacao, for example, doesn’t infect mango. Occasionally, however, a genetic change in a strain of the fungus can lead to the development of a new species—one that is primed to attack a new host.

According to researchers, this was the case with ʻōhiʻa. Lab tests showed that fungus collected from ʻōhiʻa wouldn’t grow on other known Ceratocystis hosts in Hawaiʻi, suggesting that ʻōhiʻa was possibly hosting a new species of the fungus. Working with specialists, they intensively examined the fungi’s structures and life cycles and used DNA analysis to describe and classify the pathogen. In a surprise twist, Keith and her team discovered that they were dealing with not one, but two versions of Ceratocystis: both attacking ʻōhiʻa, and both never before described by science.

“What a surprise,” said Keith, discussing the results. “It’s not every day that a new fungal species is discovered, so to find two at the same time, attacking the same plant, is quite remarkable.” According to the genetic results, the fungi weren’t even closely related—one had DNA most similar to Ceratocystis in Asia, while the other claimed roots in Latin America.

Naming the species

When a new organism is found, the discovering scientist holds the responsibility of giving it a name. Because these fungi appeared for the first time in Hawaiʻi and attacked the revered ʻōhiʻa lehua, Keith felt it was important to consult with Hawaiian cultural experts in naming the new species. “I wanted to select Hawaiian names to reflect what was happening to the ʻōhiʻa. I consulted with Kekuhi [Kealiʻikanakaʻoleohaililani, of the Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation] and she consulted with her researchers and provided a short list of suggestions.”

Through a collaborative process, Keith and her team settled on the new names for the two fungal species: Ceratocystis huliohia (changes the natural state of ʻōhiʻa), and Ceratocystis lukuohia (destroyer of ʻōhiʻa). This marks the first time Hawaiian names have been given to plant pathogens. “In the Hawaiʻi world view, the presence of the fungus is a product of more than just the physicality of the disease,” says Kealiʻikanakaʻoleohaililani. ”The names are necessary because the “thing” we need to confront and remove from our reality must have a name.”

C. huliohia causes a canker disease beneath the bark. It spreads slowly throughout the tree, killing off localized areas of water-conducting tissue which eventually causes the tree to die. C. lukuohia, however, is the more aggressive and deadly of the two, causing a systemic wilt. It too chokes off the water supply to the tree, but quickly – often causing the entire crown of the tree to go brown almost all at once. Both are considered causes of Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death.

While the authors were unable to determine the exact origin of these new species, the lack of genetic diversity in them indicated that both pathogens were recent introductions to Hawaiʻi. According to Keith, the fungi were either brought here in their current form or evolved from interacting with other introduced Ceratocystis strains, most likely on propagated plant material. Such imports are a common pathway for introduction of other Ceratocystis fungi around the world, and are considered a high risk pathway for the introduction of new plant diseases in Hawaiʻi.

The new information helps researchers who are searching for methods to stop the spread of Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death in Hawaiʻi. J.B. Friday, extension forester with UH Cooperative Extension Service, who was involved from the start of efforts to research and manage Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death praised the new findings. “It is important to know the classification of the pathogens so that quarantine regulations can be drawn up to restrict the movement of the fungi. Knowledge of related diseases might give researchers clues as to how to fight Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death and keep remaining ʻōhiʻa forests healthy.”

Learn more about Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death at the UH Mānoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources.

Read more about Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death at UH News.