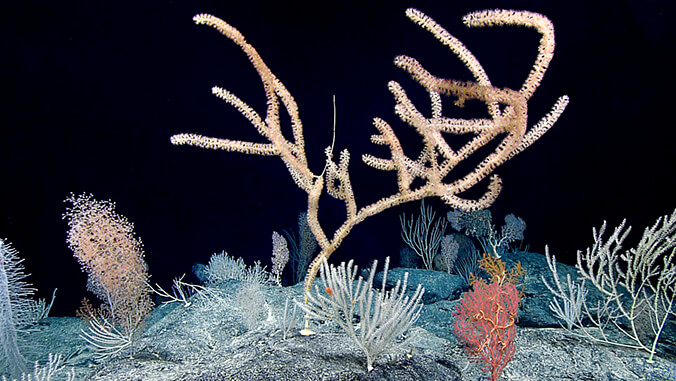

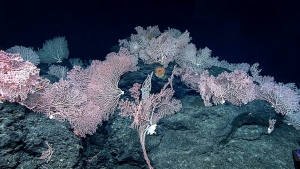

The deep-sea, ocean depths below 650 feet (200 meters), constitutes more than 90 percent of the biosphere, harbors the most remote and extreme ecosystems on the planet, and supports biodiversity and ecosystem services of global importance. A new publication on the impacts of deep-seabed mining by 13 prominent deep-sea biologists, led by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Department of Oceanography Professor Craig Smith, seeks to dispel scientific misconceptions that have led to miscalculations of the likely effects of commercial operations to extract minerals from the seabed.

Interest in deep-seabed mining for copper, cobalt, zinc, manganese and other valuable metals has grown substantially in the last decade and mining activities are anticipated to begin soon.

“As a team of deep-sea ecologists, we became alarmed by the misconceptions present in the scientific literature that discuss the potential impacts of seabed mining,” said Smith. “We found underestimates of mining footprints and a poor understanding of the sensitivity and biodiversity of deep-sea ecosystems, and their potential to recover from mining impacts. All the authors felt it was imperative to dispel misconceptions and highlight what is known and unknown about deep-seabed mining impacts.”

Far-reaching impacts

In addition to the impacts of mining on ecosystems in the water above extraction activities, detailed in another UH-led study, Smith and co-authors emphasize deep-seabed mining impacts on the seafloor, where habitats and communities will be permanently destroyed by mining.

“The bottom line is that many deep-sea ecosystems will be very sensitive to seafloor mining, are likely to be impacted over much larger scales than predicted by mining interests, and that local and regional biodiversity losses are likely, with the potential for species extinctions,” said Smith.

The scope of mining impacts from full-scale mining will not be well understood until a full-scale mining operation is conducted for years. The geographic scale and ecosystem sensitivities to mining disturbance occurring continuously for decades cannot be simulated or effectively studied on a smaller scale, according to the authors.

“All the simulations conducted so far do not come close to duplicating the spatial scale, intensity and duration of full-scale mining,” added Smith. “Further, the modeling of impacts uses ecosystem sensitivities derived from shallow-water communities that experience orders of magnitude higher levels of turbidity and sediment burial (mining-type perturbations) under natural conditions than most of the deep-sea communities targeted for mining.”

Effective management

Much of the planned deep-seabed mining will be focused in the Pacific Ocean, near Hawaiʻi, and also near Pacific Island nations. Hawaiʻi and Pacific Island nations are likely to suffer from any negative environmental impacts, but may benefit economically from deep-seabed mining, creating a need to understand the trade-offs of such mining.

For more see School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology’s website.

–By Marcie Grabowski