Earth is orbited by thousands of artificial satellites, but only one large, natural Moon. Eight years ago, researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi Institute for Astronomy (IfA) predicted that there must be a population of small, natural ‘minimoons’ that temporarily orbit Earth. On November 22, a team of 23 researchers from 14 academic institutions announced a study on the second minimoon ever discovered, dubbed 2020 CD3.

The team, which includes seven current or former IfA researchers, discussed the discovery and detailed characteristics of the new minimoon in a paper published in Astronomical Journal.

Kacper Wierzchos and Teddy Pruyne discovered the minimoon using the 1.5m Mt. Lemmon telescope, operated by the Catalina Sky Survey at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Tucson.

Distinguishing minimoons from ‘space junk’

One of the major difficulties in studying minimoons is that they require detailed observations to establish that they are not merely artificial “space junk” like the recently-discovered object known as 2020 SO, found earlier this fall by IfA’s Pan-STARRS1 survey telescope on Haleakalā, Maui.

The new research paper conclusively shows that 2020 CD3 is a natural object between the size of a small dishwasher and a refrigerator, likely a fragment of a larger asteroid that orbits the Sun somewhere between Mars and Jupiter. Extensive follow-up observations were needed to accurately determine the object’s orbit.

“The high-precision astrometry we obtained from the University of Hawaiʻi 2.2-meter telescope and the Canada-France-Hawaiʻi Telescope on Maunakea was absolutely essential to confirm that 2020 CD3 is a captured asteroid, and not something artificial,” said Dora Föhring, IfA researcher and paper co-author.

“It is incredible that modern astronomical telescopes can detect minimoons the size of big boulders as far away as the Moon,” added IfA Astronomer Robert Jedicke, a co-author on the paper.

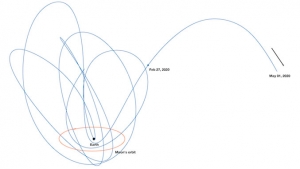

The team’s calculations indicate that 2020 CD3 had been orbiting Earth for over two and a half years, but was only discovered as it made a very close approach to Earth, before being flung back out into an orbit around the Sun. Jedicke’s work showed that, even though it was bright enough to be detected at least half a dozen times in the past few years, there were only one or two opportunities when it was bright enough and moving slowly enough to be discovered.

Minimoons pose no danger to Earth, even though about 1 out of every 1,000 meteors that strike Earth are actually tiny minimoons before they enter Earth’s atmosphere.

Asteroid mining techniques

In the future, minimoons may be interesting targets for both scientific study and to practice asteroid mining techniques. A dishwasher-sized minimoon weighs more than a ton, and would yield critical clues about the formation of our solar system.

“[Minimoons are] outstanding targets for space missions,” said Grigori Fedorets, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral research fellow at the Astrophysics Research Centre at Queen’s University in Belfast. “Minimoons effectively bring the asteroid belt close to the Earth so that, in astronomical terms, we can reach out and touch them, and potentially collect samples.”

Jedicke is excited about the opportunity to use minimoons to test asteroid mining technology. “It is difficult to monitor and control spacecraft around distant asteroids where it can take many minutes to verify that a single command has been properly executed. Minimoons are so close to Earth that we can imagine using a joystick at ground control to perform mining operations,” he said.

2020 CD3 is once again orbiting the Sun, but it is possible that it will one day return and dance with the Earth. In the meantime, there will be other minimoons to be studied and Fedorets expects that many will be discovered by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, currently under construction in Chile and expected to begin operations in 2022.