Bacteria alter their swimming patterns when they get into tight spaces—hurrying to escape from confinement, according to a published study by researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Nearly all organisms host bacteria that live symbiotically on or within their bodies. The Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, forms an exclusive symbiotic relationship with the marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri, which has a whip-like tail that it uses to swim to specific places in the squid’s body.

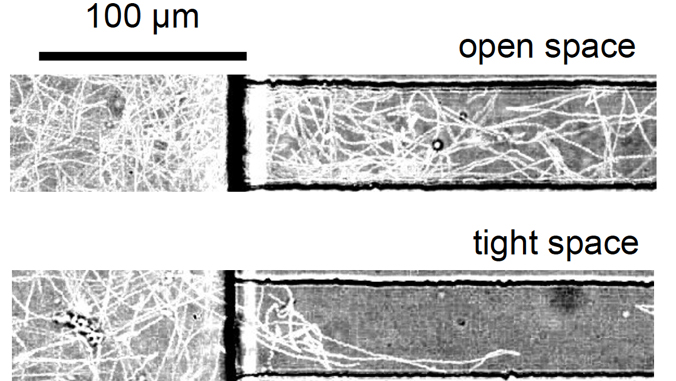

A research team, led by Jonathan Lynch, who was a postdoctoral fellow at the Pacific Biosciences Research Center at the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, designed controlled chambers in which they could observe the Vibrio bacteria swimming. Using microscopy, the team discovered that as the bacteria moved between open areas and tight spaces they swam differently.

In open spaces, without chemicals to be attracted to or repelled from, bacteria appeared to meander with no discernible pattern—changing direction randomly and at different points in time. Upon entry into confined spaces, the bacteria straightened their swimming paths to escape from confinement.

“This finding was quite surprising,” said Lynch, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles. “At first, we were looking for how bacterial cells changed the shape of their tails when they moved into tight spaces, but discovered that we were having trouble actually finding cells in the tight spaces. After looking more closely, we figured out that it was because the bacteria were actively swimming out of the tight spaces, which we did not expect.”

Navigating a complex environment

The relationship between the squid and this bacterium is a useful model of how bacteria live with other animals, such as the human microbiome. Microbes often traverse complicated routes, sometimes squeezing through tight spaces in tissues, before colonizing preferred sites in their host organism. A variety of chemicals and nutrients within hosts are known to guide bacteria toward their eventual destination. However, less is known about how physical features like walls, corners and tight spaces affect bacterial swimming, despite the fact that these physical features are found across many bacteria-animal relationships.

“Our findings demonstrate that tight spaces may serve as an additional, crucial cue for bacteria while they navigate complex environments to enter specific habitats,” said Lynch. “Changing swimming patterns in tight spaces may allow some bacteria to quickly swim through the tight spaces to get to the other side, but for the others, they turn around before they get stuck—kind of like choosing whether to run across a rickety bridge or turn around before you go too far.”

In the future, the researchers hope to figure out how these bacteria are changing their swimming activity, as well as determining if other bacteria show the same behaviors.

This work was funded by the UH C-MAIKI Initiative, the Ford Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

This research is an example of UH Mānoa’s goal of Excellence in Research: Advancing the Research and Creative Work Enterprise (PDF), one of four goals identified in the 2015–25 Strategic Plan (PDF), updated in December 2020.

–By Marcie Grabowski