Exploring the icy cold depths of the frozen continent of Antarctica could be considered a research career highlight, and a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa associate professorʻs work has taken her to the chilling sea at the bottom of the world, not just one time, but three.

Amy Moran of the School of Life Sciences, along with her PhD zoology students, Aaron Toh and Graham Lobert with the Moran Lab, departed for McMurdo Station, Antarctica in October for their second season of a multi-year $458,791 project funded by the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs in 2018. They spend their days diving under the ice studying marine animals that live in the Southern Ocean, the coldest ocean in the world. Animals that live there have lived in freezing temperatures (-1.8° C or 28° F) for millions of years.

“We collect a variety of invertebrates including sea spiders and nudibranchs, and work in the laboratory to test the developmental and metabolic effects of small increases in temperature on the least-well-understood early stages of the life cycle; the eggs, embryos and larvae,” said Moran, who led her project team the first time in September 2019—February 2020.

According to Moran, the animals they study have adapted to constant and extreme cold, and many cold-blooded animals have lost the ability to cope with even slightly warmer temperatures. “When the environment gets warmer, they have nowhere colder to go, making them more vulnerable to warming oceans and other factors that go along with global climate change,” she said.

This is Moran’s third grant to work in Antarctica, and second grant funded through UH. Her research interest in the ecology and evolution of marine invertebrates led to her previous discovery with PhD student Caitlin Shishido, that a bizarre group of sea spiders in Antarctica breathe differently than other animals—through their legs.

Diving beneath the ice

The ice around McMurdo Station is between 7–9 feet thick, so the team drills holes in the sea ice to access the ocean below. “Because it is difficult to get a drill out to remote sites, we’ll sometimes find seal holes that we can expand with an ice pick and saw,” Moran explained.

Dives can last up to an hour, but average about 30–35 minutes. Depth is a limiting factor because of their no-decompression diving to minimize risk of decompression sickness. “We generally start feeling cold after around 20 minutes, although some days feel warmer than others (not because the freezing water is any different),” Moran said.

While the “super cold” waters limit their diving time, “it’s a magical experience if you’re properly trained for it!” Toh added. “The diversity of species under the ice is fantastic! Aside from curious seals, there are massive sea spiders, sponges, crinoids and other invertebrates that just amaze you every time you dive.”

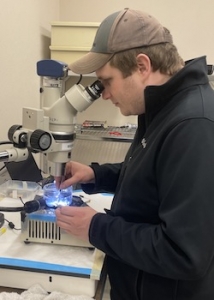

Lobert spends most of his time in the lab, and assists Moran and Toh in and out of the water. “I get to work with some truly amazing organisms, and can’t think of a better place to research as there are so many interesting questions that can be asked about the organisms that inhabit these frigid waters,” he shared.

The team works every day, but takes personal time when they need to. McMurdo Station offers the researchers a gym, library, outdoor activities such as skiing, and pizza in the gallery 24 hours a day. “We were even treated to a huge Thanksgiving feast with turkey, pumpkin pie and all the fixings!” Moran said.

Moran is planning her return from the ice in December, while Toh and Lobert are extending their stay till February 2022. The UH team has another year or more of lab work to analyze the samples they’ve collected.

“Every trip to Antarctica is a trip of a lifetime, and we’re all looking forward to coming back some day,” Moran said.

Training with UH Diving Safety Program

Working in Antarctica required months of preparation for the UH team, including training intensively with the UH Diving Safety Program, the authoritative source for all student, faculty and staff divers who conduct official UH research or educational activities in the water. Moran and her students received specialized SCUBA diving training including practicing to use a drysuit and refining their drysuit buoyancy skills. It was a “less-than-comfortable” experience that took some getting used to in Hawaiʻi, according to Toh.

“The UH Diving Safety Program is amazing and we love working with them,” Moran added. “UH has one of the largest scientific diving programs in the U.S., and we scientists are so grateful to have such a strong and expert group support our work and prepare us for Antarctica.”

This work is an example of UH Mānoa’s goal of Excellence in Research: Advancing the Research and Creative Work Enterprise (PDF), one of four goals identified in the 2015–25 Strategic Plan (PDF), updated in December 2020.

—by Arlene Abiang